The penalty for getting caught trying to escape, according to the Geneva Convention, was ten days in solitary confinement. The reality was death.

Jack Lyon passed away in his home at Bexhill-on-Sea at the age of 101. He was one of the last remaining veterans of the Great Escape in World War II. His death comes just two weeks before the 75th anniversary of that event on March 24, 2019.

He served as a navigator in the Royal Air Force (RAF) and was a lookout during the famous escape from Stalag Luft III in 1944. The tunnel used was discovered before he was able to make his own escape.

He believes that the discovery may have actually saved his life. None of the actual escapees are still alive. Out of the 76 who escaped, 73 were recaptured, and 50 of those men were executed on Adolf Hitler’s orders.

Lyon gave an interview with the BBC on his 100th birthday in 2017. In that interview, he said that he had known at the time that, had he successfully escaped, he would have had almost no chance of making it home alive.

The escape was the subject of a Hollywood film starring Steve McQueen in 1963. Lyon characterized the movie as “absolute rubbish.” He said that no Americans were involved in the escape and the famous motorcycle from the film was not a part of the real event.

Air Vice Marshal David Murray is the chief executive of the Royal Air Force Benevolent Fund (RAFBF). He said that Lyon belonged to a generation of veterans that we are losing as time passes. He said our current freedoms are the legacies of Lyon and his comrades.

Stalag Luft III was one of the Nazis’ most secure prisoner of war camps. Roger Bushell was an RAF pilot who had been captured after being shot down while helping with the evacuation of Dunkirk. He was sent to Stalag Luft III after escaping from two camps previously.

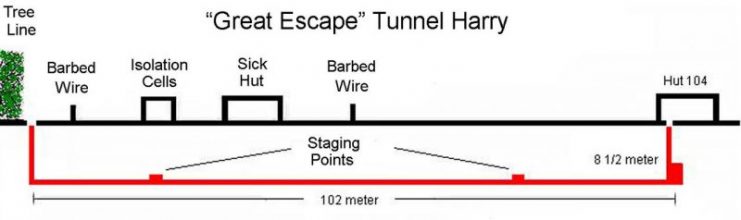

Stalag Luft III was designed to be secure. Prisoner huts were raised off the ground so that they could not dig tunnels from within. Microphones were buried underground around the perimeter fence. The camp was built in an area of sandy ground which would be difficult to tunnel through.

Still, Bushell was unfazed. In the spring of 1943, he worked with other prisoners to develop an escape plan. The plan called for three tunnels which were named “Tom,” “Dick,” and “Harry.” The tunnels would run for 300 feet (91 meters) under the outer fence of the camp. They would be dug 30 feet (9 meters) deep to avoid the microphones.

The penalty for getting caught trying to escape, according to the Geneva Convention, was ten days in solitary confinement. The men decided that it was worth the risk.

Fashioning tools and equipment from whatever they could scavenge in the camp, they began digging tunnels. Sand from the digging was placed in pouches in their pants and released as they walked through the camp, distributing the sand gradually so that it was unnoticed by the guards.

An expansion of the camp left the tunnel known as “Dick” with no exit point. This became useful in the winter when it was no longer possible to spread the sand from the excavation over the dirt. Instead, they began filling Dick with the sand from the other two tunnels. They were also able to store clothing, falsified papers, and other items associated with the escape in the closed tunnel.

Eventually, “Harry” was completed and the escape was set. Of the 600 prisoners who worked on the tunnels, only 200 could make the escape. The actual escape attempt was complicated by winter weather, an Allied air raid, and a collapse in the tunnel.

Read another story from us: Spitfire Flown by ‘Great Escape’ Pilot Found on Norwegian Mountain

The 77th man was seen leaving the tunnel, so the other 76 fled. Due to the weather, they had to walk on roads and were forced to abandon many of their plans for avoiding recapture. In the end, 73 were recaptured, and 50 of those were shot under Hitler’s orders.

Air Vice Marshal David Murray is quoted as saying: “To truly pay tribute to his memory and all those who have gone before him, we must never forget.” With so few veterans of that time still remaining, that sentiment — never to forget — is even more important now than ever.