Stalags were camps created by the Wehrmacht armed forces to keep prisoners of war who belonged to the rank and file. These places were created with one purpose in mind – using the work of prisoners and turning their short life into hell.

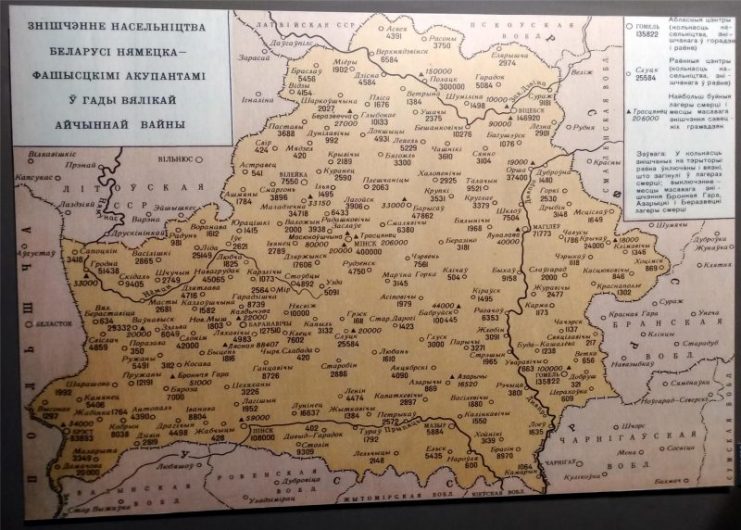

In June 1941, during the years of the occupation of Belarus in the Minsk region near the village of Masyukovshchina, the Germans created a camp for Soviet prisoners of war – Stalag No. 352.

Stalag No. 352 in its structure had two sections: the City Camp, located in Minsk, and the Forest Camp near the village of Masyukovshchina. In addition, Stalag No. 352 had more than 90 branches at railway stations and 22 branches in the city of Minsk.

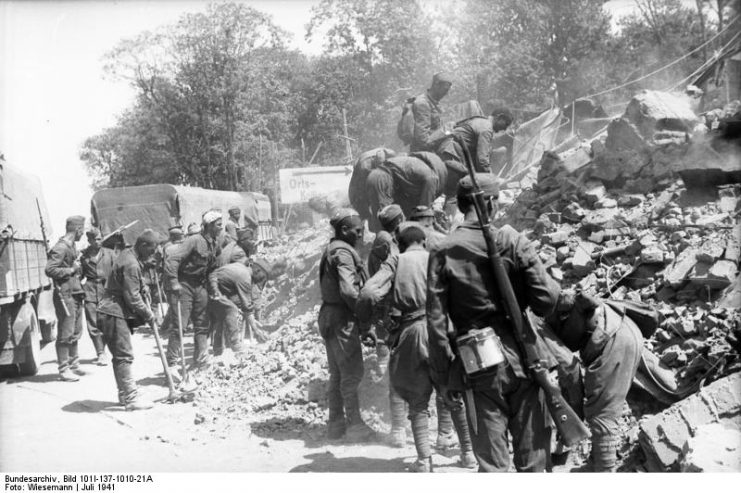

From the first days of its existence, the camp was crowded. Prisoners of war were delivered by rail. German soldiers using brute physical force drove prisoners of war from the wagons. Those who refused to go or walked too slowly were shot on the spot. There were not enough places to accommodate the prisoners, and so many (80%) were left to sleep “in the open,” even in winter. Later, the Germans organized the construction of additional tents.

Not life, but survival

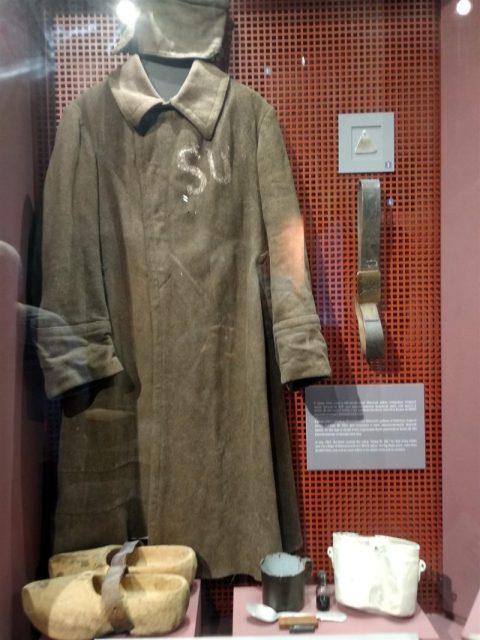

Before entering the camp, all prisoners were deprived of their old clothes. In return, they were given old and worn special camp clothes. Old and worn because this clothing was often removed from the dead bodies of prisoners for reuse.

An inscription left by a prisoner on the wall of a punishment cell:

“Comrades, prisoners of war and commanders, fight against the German invaders and murderers. Soon the hour of reckoning will come, and then the fascist bastards will pay for Russian blood.”

The camp was further divided into sections depending on the place of birth, views and religious affiliation of the prisoners. There were separate sections for Jews, Russians, Ukrainians, and officers. In the various sections stood barracks fenced with impassable wire.

The barracks in which the captive prisoners were located were not intended for winter residence. They did not have heating, there was no decking so under the feet was bare earth. In such premises, it was always very cold. There was a terrible smell of unwashed human bodies and sewage.

There were not enough places for sleep, and so there were always several people sleeping on the “shkonka” (wooden bunks usually 3 levels high, but designed for 1 person). There have been cases where the wooden bunks on which the prisoners slept broke so that they fell on the lower tier, where other people slept.

In addition, the prisoners were forbidden to move at night or to leave the barracks – if you did you could get a bullet.

For the administration of the camp, there were comfortable and warm rooms. They did not deny themselves convenience, food and rest. Some Germans preferred to live in villages nearby.

Food worse than that given to animals

Food in the camp came under the charge of the Economic Inspectorate of the Wehrmacht Command located in Ostland. According to the decision of the Inspectorate, each prisoner received 4-8 ounces of bread ersatz and about half a pint per day of water or soup. All food was of the lowest quality.

Sometimes, instead of water, technical oils were used. Often this was in the form of a soup, consisting of cooked rotten potatoes and straw. Bread often contained straw and sawdust and was infected with mold, causing an epidemic of dysentery among the prisoners of the camp.

As punishment, the fascists used forced starvation. In most cases, the death of a prisoner was a combination of the terrible quality of food and exhaustion. There were cases where once a day the Germans threw rotten potatoes near the perimeter fences. Exhausted from hunger, people fled to this “food”, and when they did, the sentries opened fire. As a result of such poor nutrition and inhumane treatment, the death rate in the camp increased to 100-150 people a day.

In November 1941, an epidemic of typhus began in the camp. Medical assistance for prisoners was not provided. As a result, throughout the winter of 1941-42, about 55 thousand people died.

Deadly work

Those refusing to work or for working too slowly were sent to the punishment cell. The floor of the punishment cell consisted of concrete, and overhead, at a height of about 4 feet, was stretched mesh of barbed wire. Any natural precipitation (snow or rain) passed through it. The prisoners were in a half-bent state – it was not possible to lie down or stand up to their full height. Entry to the punishment cell was often a painful death sentence.

The strongest and healthiest prisoners were gathered into labor collectives. They worked inside the camp and beyond. Each team was assigned a “senior” who was responsible for his team.

The workers of Stalag No. 352 worked at many different enterprises that were of interest to the Wehrmacht. Often they did the hardest and dirtiest work. The prisoners worked in factories and warehouses extracting minerals.

The main labor activity outside the City Camp was carried out at the railway stations (more than 90) in and around Belarus. The work included the unloading and loading of wagons, their repair, heavy repairs of railroad tracks and more.

Those who worked received more food, but at the same time, they were more likely to die from physical exhaustion and serious injuries. Everyone was afraid of death, but sometimes it seemed the best solution. Either you work and suffer or you refuse and perish.

Nowhere to run

The Germans severely punished those who tried to escape from the camp. For attempting to escape prisoners were hung on a huge hook and left to die. Hanging there, the prisoner suffered a slow and excruciating death.

At the perimeter of Stalag No. 352 there were fire points and guard posts armed with machine guns. At each corner were towers with searchlights. On all sides, a double row of seven-foot high fences, the posts of which were covered in barbed wire surrounded the camp. Exhausted and desperate prisoners could not find the strength to overcome such barriers.

Fragment from the memoirs of former prisoner A.G. Voronov:

“People who have not been washed for several months have been devoured by lice. The water in the barracks was completely absent. People gathered snow mixed with mud and quenched their thirst. Feeding people took place in the yard and lasted for three to four hours each time. Exhausted, sick people, who did not have shoes in the majority, were barely dragged on receiving food, for which the Germans mercilessly beat them with clubs. “

Stalag No. 352 existed until July 1944. The result of its activities were the corpses of more than 80,000 people. All of them were buried in large pits near the village of Glinische. When the city of Minsk was liberated, the forest camp near the village of Masyukovshchina was used by the Russians to keep German prisoners of war.

“Eternal memory to you, the sons of the Soviet people” is a book containing names and information about the Soviet prisoners of war who died in Stalag number 352. In 1964, on the site of mass graves in the area of the village of Masyukovshchina, a memorial was built.