On April 22, 1915, the Germans released 6,000 canisters – around 168 tons – of chlorine gas.

Of all the weapons developed and deployed by the belligerents involved in the First World War, poisonous gases were some of the most brutal and inhumane. The various gases used include chlorine gas, phosgene, and mustard gas.

While France was the first country in the war to deploy gas in an attack (they used tear gas in August 1914 against the Germans) the first lethal and devastating gas attack was perpetrated by the Germans during the Second Battle of Ypres in April 1915.

During this attack, in which chlorine gas was used, over 1,100 Allied soldiers were killed, most of whom were French-Algerian and Canadian troops.

Chlorine, a diatomic gas, is a pale, greenish-yellow in color and has a sharp, easily identifiable smell. The effects of breathing it in are devastating since it reacts with water to form hydrochloric acid, which burns and dissolves living tissue.

If inhaled, it can cause death in minutes. If the victim survives, they are likely to have permanent lung damage.

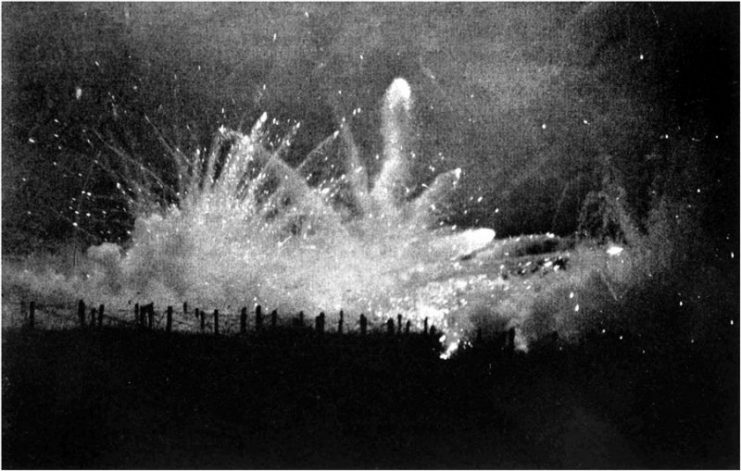

On April 22, 1915, the Germans released 6,000 canisters – around 168 tons – of chlorine gas along a three and a half mile stretch of the front near Ypres, Belgium.

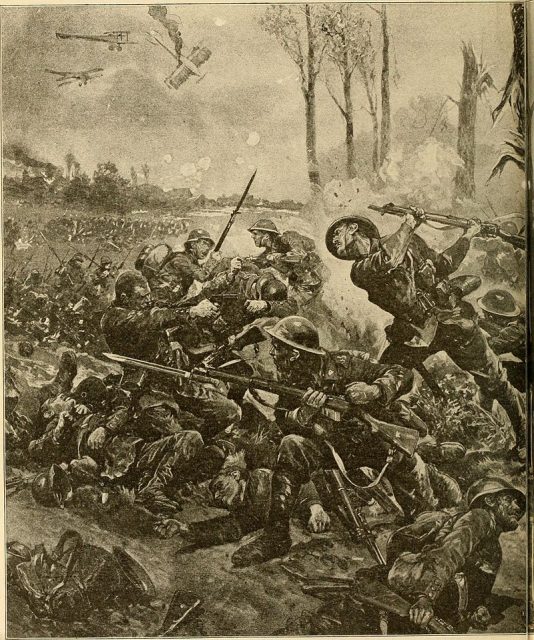

The wind carried the huge cloud of gas over to the Allied trenches. The troops in these trenches did not know exactly what the 20-foot yellow cloud drifting towards them was; they had no idea how to react.

As the ominous cloud of chlorine gas began to reach the Allied lines, the Germans opened up a withering barrage of machine gun fire. Their aim was to force the Allied troops to take cover in their trenches, which was the worst possible place to be during the gas attack.

This is because chlorine gas is heavier than air, and therefore will be most heavily concentrated at the lowest points of a landscape – in this case, the bottom of the trenches.

Of course, the Allied troops did not know this, so they ducked down into their trenches as the yellow cloud rolled over them… and then they started dying.

The effects of the gas were so devastating that the French-Algerian troops broke ranks and fled. Those who had breathed in lungfuls of the gas were dying like flies.

Those who survived described seeing thousands of men dead, with the dying lying on the ground desperately trying to drink water from puddles and ditches, which only added to their agony.

Many who survived the attack were nonetheless incapacitated by it, their eyes temporarily blinded by the chlorine gas. Troops would have to move around in trains, each blind man gripping the shoulders of the soldier in front of him, with those who could still see leading them all.

While the abandoned French-Algerian positions created a huge gap in the Allied lines, the Germans – possibly underprepared for and stunned by just how savagely effective this new weapon was – failed to exploit the opening by throwing the full weight of their numbers at it in an all-out offensive.

They certainly did try to capitalize on the success of the attack though, and it was only through the steadfast courage and grit of the Canadian First Division, who threw their all into re-manning the trenches and holding the line, that the Germans were prevented from taking the Allied position.

During the next 48 hours, the Canadian troops would engage in a number of fierce, sustained battles to prevent a German breakthrough.

On April 24, the Germans launched another gas attack, this time aimed at the Canadians. While they were somewhat prepared for it, unlike the Algerian troops, it still had a devastating effect.

During this two day period, one in every three Canadian troops who fought was wounded, and one in every nine was killed.

The Allies prevailed though, and the line was ultimately held.

Shortly after the first poison gas attack of the First World War, the British and the French began developing their own chemical weapons. On September 25, 1915, the British attacked the German trenches with gas at Loos, Belgium.

By the end of the war, the Allies had actually ended up using more poison gas than the Germans.

Read another story from us: When the British 1st Used Poison Gas – Battle of Loos

The site where so many Algerian troops lost their lives in such a horrific manner to the first ever gas attack and where so many Canadian troops gave their lives to hold the line, is now marked by an impressive memorial.

The Saint Julien memorial – a 36-foot tall column topped by a sculpture of a Canadian soldier with a bowed head – towers majestically over the landscape. It provides a fitting, permanent memorial to all those who lost their lives at the Second Battle of Ypres.