War History online presents this Guest Piece from Jack Snowden

The story of the Emden, a German warship that single-handedly harassed primarily British shipping in the Indian Ocean in the early days of World War I, is well known among those familiar with the war. In November of 1914 the Emden was finally destroyed by the Australian cruiser HMAS Sydney, near Direction Island in the Keeling Island group, but a landing party, led by the Emden’s Executive Officer Hellmuth Von Mücke, escaped capture by the Australians and went on to accomplish an amazing journey back to Germany, as detailed in WHO by Gabe Christy.

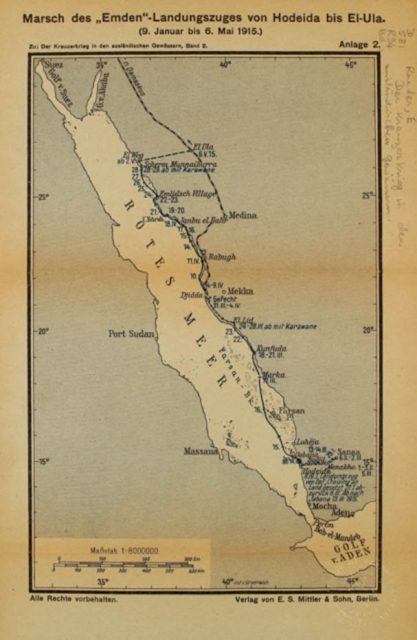

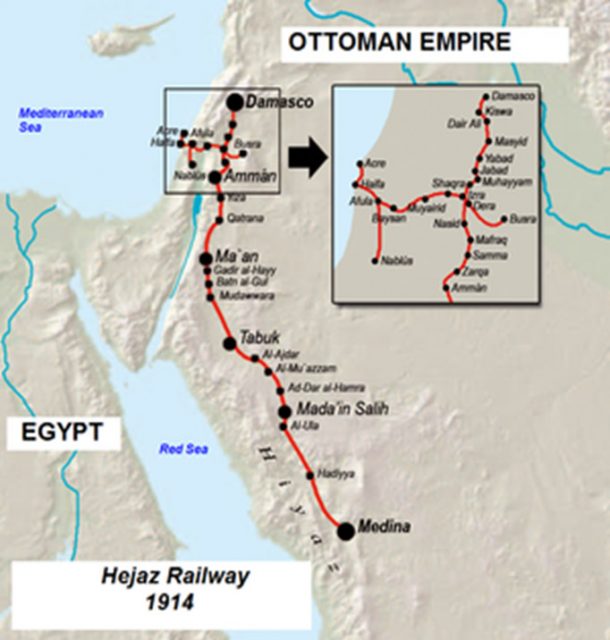

A portion of the Emden crew’s return trip passed along the eastern Red Sea coast, then a part of the Ottoman Empire, Germany’s wartime ally, as the party attempted to reach the Ottomans’ Hijaz railway further north that would take them safely back to Istanbul, and from there to Germany. The details of this Red Sea coast episode are usually skipped over in accounts of the Emden crew’s return because the journey was filled with so many other remarkable episodes. However, one person intimately familiar with the transit was Sami Çölgeçen, an Ottoman official who happened to be in Al Qunfidah, on the Red Sea coast, in the early months of 1915 after finishing up some Ottoman affairs across the water in Egypt and Ethiopia. When the Emden crew arrived at the Arabian peninsula aboard the German merchant ship Choising in early 1915, they first landed at Hodeida, further south, and after a failed attempt overland, took small boats north to Al Qunfidah, arriving there in late March. As colorful a character as Von Mücke, Çölgeçen’s past included years of exile at the behest of Ottoman Sultan Abdülhamid II, in Fizan, Libya, and his incredible escape in 1908 across the Sahara Desert. After Abdülhamid II was deposed, Çölgeçen returned to Fizan, but this time as its governor.

It was the Istanbul newspaper Milliyet in 1927 that took notice of Von Mücke’s memoir, in which he characterized Çölgeçen in this manner: “in al Qunfida we encountered a minor Turkish official and took him along with us as translator.” Milliyet tracked down Çölgeçen, at that time an regional Inspector General of the ruling Republican Peoples Party in the new Turkish Republic, and asked him to respond to Von Mücke’s characterization, which Çölgeçen did by writing a 6-piece series in Milliyet in mid-June 1927. Çölgeçen’s account of the Emden crew’s Red Sea coast transit was his effort to set the record straight.

“Von Mücke Corrupts the Truth”

“As Von Mücke wrote, he reached Al Qunfidah disheveled and exhausted on 17 March 1915, together with his crew of 6 officers and 47 sailors. When he saw me he requested that I take care of them. I was on duty in Al Qunfidah, dealing with a delegation related to the south of Egypt and Addis Ababa. My duty was completed, with only the communications aspect remaining and I turned this over to the very competent Al Qunfidah district chief Kemal Bey. I undertook to transport Von Mücke and his crew as a fellow soldier, because to turn them loose on their own in the desert and sea would mean their end. Any Turk would have done the same, not just me. We provided Von Mücke and his crew with every kind of support. Nevertheless, niether in Von Mücke’s travel log nor in the sea battles that Adbidin Daver Bey translated is there any mention of Turks, who gave physical and morale support, even shedding blood in the process. In his memoir, Von Mücke mentions myself and my wife indifferently, referring to me as a minor Turkish official whom they took along as a translator. In fact, I was the governor of Al Qunfidah, as I had been in Tunis and Tripoli. In truth, I was very disappointed at how this world-famous German officer, with whom I faced every sort of danger, could so blatantly corrupt the truth. Consequently, I consider it my duty to explain the roll of the Turks in this journey and to show how we got Von Mücke and his crew to the Hijaz rail line. I hope that Abidin Daver Bey will pass along my writings to Von Mücke and to the writers of sea battles. Additionally, I hope that Von Mücke will extract those offending lines from his book and reveal the truth to his countrymen and readers all over the world. Right now I can only write a small portion but when my journals are published more of the truth will be understood and it will be seen that during the World War the Germans stood on the shoulders of their Turkish comrades to raise themselves up.”

Up The Red Sea Coast, Ambushed by Bedouins

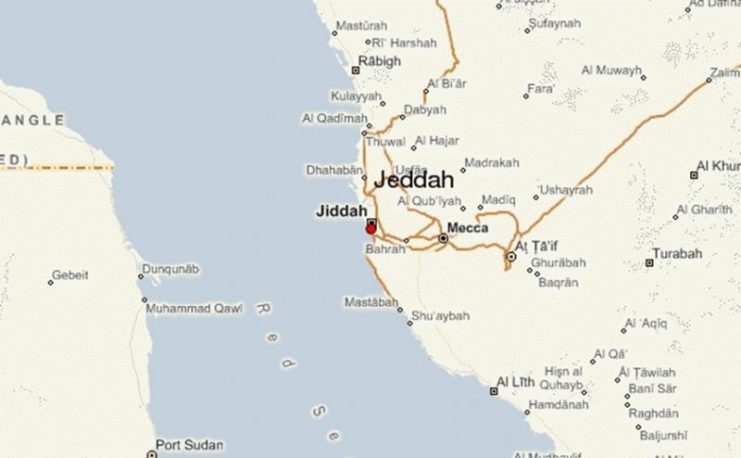

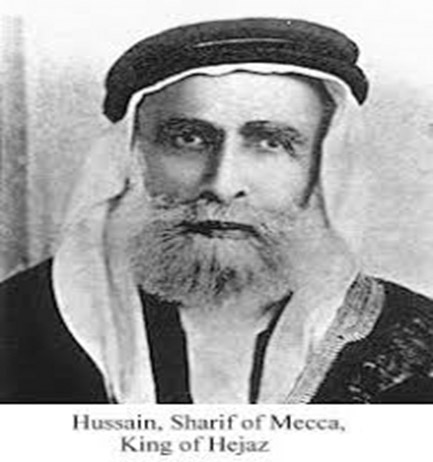

In any case, Çölgeçen made arrangements for a new boat for the Emden crew and on 19 March the Çölgeçen-Von Mücke party set sail from Al Qunfidah, reaching Al Lith on 24 March. The local Ottoman district chief in Al Lith advised Çölgeçen that further travel by sea to Jiddah would be problematic, though, because “there are English ships at Jiddah and they’re searching every boat, arresting everyone on board on the slightest suspicion.” The only alternative was a grueling overland trek, which the Çölgeçen-Von Mücke party initiated on 31 March, accompanied by Şerif Nâsır, the Al Lith representative of Sharif Hussain, the Emir of Mecca.

Moving slowly up the coast, the party was joined on 18 April by a guide named Şerif Salih, who had been sent by the Sharif Hussain. Çölgeçen’s suspicions about Sharif Hussain were growing, as this passage reflects:

“In the evening, just as we were about to leave, Şerif Salih, whom the Emir had sent, came to me and insisted that we stay the night and leave the next day. At the same time, Lieutenant Hikmet Bey came and said that the Gendarmerie agreed with this. (I later learned that this gendarme was a local and one of Sharif Hussain’s men). They planned to ambush us at the well head and massacre us. I replied that it was not possible to change our plan and that this was our duty, not theirs. At this point, Sharif’s man Şerif Salih came to me and again said that the convoy should stop here. Of course, I refused and we pressed on. Around 0400, the Arabs, who were hidden in the grass, ambushed us and began firing, screaming “Hâyâ evlâd!”. We all fired at the Bedouins haphazardly until the machine guns were unloaded from the camels. Gendarmerie Captain Mustafa Bey was extremely effective in getting the machine guns in place. The Bedouins surrounded us on every side and we took the following measures: Von Mücke was in front and Captain Mustafa Bey in the rear, each with a machine gun firing at the Bedouins. The other officers and soldiers fired from the sides. I had the ammunition boxes located and opened. I sent the ammunition to Ahmed, who had been a war prisoner with me, and to Von Mücke. My wife and I then began to distribute ammunition to the soldiers and officers. During the battle, Von Mücke performed heroically. He had the soldiers mount their bayonets and they charged, scattering the Arabs from their ambush positions and giving us some breathing room.”

The Çölgeçen-Von Mücke party’s battle with Bedouins settled into a stalemate so Çölgeçen, who was fluent in Arabic, met with them to make and arrangement for safe passage:

“Ultimately, I addressed the chiefs and their Bedouin aides and explained that this was a very serious situation, emphasizing that the government would pursue them if anything happened to us. I noted that the Germans were our guests and our military allies and that because of Suez together we would defend the Hijaz. I insisted that we had plenty of water and ammunition and that we could inflict many more casualties on them. In addition, I warned them that the government would soon be coming to look for us. It would be better for them to take the money and reach a cease-fire, I said. In order to cause rifts between them I explained how much 10,000 liras would amount to in riyals and said they would each get a nice portion of it, allowing them to improve their lot rather than ride around destitute and dismayed, with just one shirt on their back all the time. This talk of money made the Arabs wide-eyed – it is their most sensitive spot.”

Safe Arrival in Jiddah, Sharif Hussain’s Ulterior Motives

After further adventures and missteps, Çölgeçen and his wife Nevin were finally able to reach Jiddah, while Von Mücke and his crew waited at the ambush site for rescue. But Çölgeçen’s suspicions about Sharif Hussain’s mischief had hardened, as he told the Ottoman officials who met him in Jiddah:

“I explained in reply that ‘Abdullah is not trustworthy. The mastermind of this is the Emir of Mecca and the implementer is his son Abdullah. It may be that Abdullah is mixed in with the Bedouins, keeping track of the situation.’ In response they confessed that ‘yes, we know and understand this. But we have to look the other way and go along with everything.’ Damn the ‘look the other way’ policy of the governments of the past! We we’re almost buried in the blazing sands of the Hijaz and this ‘look the other way government’ wasn’t able to send help! They assured me that the relief convoy would reach the site by tomorrow morning but I didn’t believe them. I suspected that this was another of Sharif Hussain’s tricks so I said to them ‘Since you can’t send a force, let’s have the slaves who saved us go, for goodness sake! Let’s give them some more money and have them go there by various routes and get us information about the convoy.’ They agreed to this and the gendarme Ali brought the slaves. I gave them money and instructions and they set out right away. On Sunday morning, the 22nd of April, the slaves brought the news that the convoy (Von Mücke and his crew) was on its way and towards 10 o’clock the convoy arrived in front of the barracks in Jiddah. We put the sick and wounded into the hospital.”

According to Çölgeçen, the Emir of Mecca Sharif Hussain offered to have his son Abdullah escort the Çölgeçen-Von Mücke party to Medina, where they could board the train to Istanbul. In response, Çölgeçen feigned agreement but secretly made plans with the Ottoman port officials at Jiddah to move up the coast by sea:

“On the 26th of April, with the wind at our backs, we set sail from Jiddah and began heading north. This time it was we who had given Sharif Hussain a good slap. Let’s have a drink! On the 29th of April we reached Râbig, where I asked Shaikh Hüseyin, who was an enemy of the Emir of Mecca, for a large boat. Immediately, he provided one and Von Mücke and his crew boarded it, settling in nicely. On May 5th we arrived at Yanbu. Here I told the Medine guard Basri Paşa that we would be going to Al Wajh and I asked him to ensure that the road between Al Wajh and Al’Ula was safe. Then I sent a special letter so that both Von Mücke and I could have telegrams sent.”

Reaching the Railway and Von Mücke’s New Attitude

//Map: The Emden-Çölgeçen party boarded the train to Damascus and Istanbul at Al’Ula.//

After the Çölgeçen-Von Mücke party’s safe arrival at Al Wajh on the Red Sea coast on 15 May, they traveled across the desert over 8 days and nights to the Hijaz railway station at Al’Ula. Çölgeçen related the Emden crew’s reaction as follows:

“As soon as they saw the Hijaz railway, the Germans threw their hats in the air and shouted “Hurrah! Hurrah!”. They were beyond themselves with joy. We reached Al’Ula on Wednesday, the 22nd of May. We sent word of our arrival to Yanbu and a number of German journalists came to Al‘Ula to greet the Emden crew. We stayed here for two days and in those two days Von Mücke changed his stripes. Whereas before he wouldn’t leave my side and acceded like a lamb to all my decisions, here he turned into a lion. It seems that all the congratulatory telegrams and applause served to change his attitude. Subsequently, the 4th Army Commander Cemal Paşa sent us a private train, on which there was but one first class. Right away, Von Mücke assigned this to himself and had the words “reserved” and “Von Mücke” written on it. Of course, I had my wife with me and I was injured. Besides that, my rank and position were senior to his. I wasn’t going to stand for this. In particular, the railroad was ours, the land was ours and the wood the train burned was ours. Nevertheless, without even asking, Von Mücke got all decked out, took command and had the wagon prepared for himself. That is why I had the sign removed and I settled into the wagon.”

Dinner With Enver Pasha in Istanbul, Without Çölgeçen

Following the train ride to Istanbul, the Turkish leader Enver Pasha, an ardent admirer of the Germans, fetted Von Mücke and the Emden crew, as Çölgeçen related:

“That night in Istanbul a dinner for the crew of the Emden was given by Enver Paşa, who was the acting Navy Minister, at the Maritime Ministry. Even though I was a governor and a former seaman, I was not invited. This made me very sad and I took it as an insult to Turks, more than as a personal insult. The following day I wrote a letter of protest to Talat Paşa – at that time he was Talat Bey – through his private secretary Hasan Fehmi Bey. Talat Bey was quite upset and summoned the mayor, İsmet Bey, instructing him ‘arrange a garden party in Sarayburnu Park tomorrow in honor of Sami Bey and invite the crew of the Emden!’ The next day this garden party was held and my wounded heart was healed somewhat.”

Conclusion

The details of the Emden crew’s Red Sea coast transit, as related by Sami Çölgeçen, strongly indicate that the crew’s eventual safe return to Germany would have been much less likely without Çölgeçen’s assistance. Beyond that, though, Çölgeçen’s remarks about the state of Ottoman affairs vis-a-vis the Bedouins and Sharif Hussein, in particular, in 1915, reflect the growing strength of the Arab antipathy toward Ottoman rule in Arabia, which continually gained impetus in the following two years and resulted in the effective end of Ottoman suzerainty there by the end of World War I.

As for Çölgeçen, he had been born in Berkofcha, Bulgaria in 1879 and became an Ottoman Naval officer in 1897. Almost immediately, though, Çölgeçen got into trouble for remarks and activities against the regime of Sultan Abdülhamid II and was exiled to Fizan in southwestern Libya. The exile was short and he returned to his naval duties in 1898, eventually serving as port chief in Haifa, where in 1902 he was re-arrested for spreading anti-regime material through foreign media under the pseudonym “Ali Baba” in Syria. Brought back to Istanbul, Çölgeçen was imprisoned there for 18 months and then sent back to Fizan. In 1908 Çölgeçen made a daring escape from Fizan across the Sahara Desert and returned via Lagos, the Canary Islands and Liverpool to Istanbul, where by that time Sultan Abdülhamid’s regime had been defanged. Soon afterwards, Çölgeçen returned to Fizan as its governor. Besides his time in Al Qunfida, he also served as the Ottoman governor in Necid (1914), Kerkuk (1915) and Karbela (1916) during the war years. After the founding of the Turkish Republic, Çölgeçen was a parliamentarian and an inspector general. He died in the central Anatolian city of Çankırı in 1935.

Jack Snowden, February 2018, Istanbul

All photos provided by the author.