When gunpowder weapons first appeared on the battlefields of Europe, they took the form of cannons and other artillery, huge weapons designed to cause mass casualties or knock down defenses. But these were soon joined by a very different type of weapon: early handguns.

The First Handguns

Some of the earliest accounts of these weapons come from the Hussite revolt. Around 1430, these religious rebels used gunpowder to propel missiles from hand-held tubes as they fought against their German lords in Bohemia.

By 1453, such guns had appeared in France. At the Battle of Castillon, master gunner, Jean Bureau, deployed 300 of them in a stunning victory against the English.

It marked the end of an era – both the final battle of the Hundred Years War and the moment in which handguns began their rise to dominance in Western Europe.

Early Changes

The first guns were fired using heated wires. Poked through a hole into the back of the barrel, these would ignite the charge and cause it to fire. It was an awkward process and one that reduced the soldiers’ mobility, as they had to have a fire to hand to heat the wires.

Soon, a more practical approach was found in the form of match firing. By soaking a piece of cord in chemicals such as saltpeter and alcoholic spirits, manufacturers produced something that would burn at a slow, steady rate, with enough heat to ignite gunpowder.

Touched to the hole, this was a more straightforward way to fire a gun. Gunners could carry long strings of this match around the battlefield, slowly smoldering away and ready for action.

Touching the match to the powder by hand made it harder to aim and fire a gun. Manufacturers solved the problem by adding a small pivoting arm near the back of the weapon.

This arm held the match and, when brought around, touched it to the hole. The further addition of a trigger to move the pivot meant that soldiers could ignite their powder while sighting down the length of the barrel.

Barrels gradually became longer, giving bullets more force and range. Partly as a result of this, guns became heavier. And so the early experiments turned into the first standardized guns.

The Arquebus

Sometime after 1450, manufacturers in Germany developed the first widely used and recognized handgun: the arquebus. This was a large, bulky weapon at 36-40 inches (91-101 centimeters) long and weighing ten pounds (four kilograms).

It was muzzleloading and was fired using a burning cord touched to a flash pan. This weapon set the example for other handguns over the decades that followed.

The arquebus had an effective range of only 100-200 yards (91-182 meters) but was extremely powerful up close.

It was relatively easy to train soldiers to use this gun effectively – far more so than a longbow, which required a lifetime of practice and physical adjustment. Soon, commanders were making regular use of the arquebus.

The Musket

The arquebus was followed by the musket. Even heavier and more powerful than its predecessor, this gun had to be rested on a forked prop to hold it up and keep it steady while firing.

Muskets were in use by 1503, when Spanish soldiers used them at the Battle of Cerignola.

Able to pierce the best armor at 200 yards (182 meters) and kill an unarmored man at 600 years (548 meters), the musket was a more effective weapon. Gradually, it replaced the arquebus as the weapon of choice for infantry.

But the arquebus remained in use by cavalry, as it was lighter and so could be fired from horseback, where a prop rest wasn’t practical.

Pistol Power

Around the same time, gunsmiths were developing a weapon which would prove far more practical for cavalry: the wheel-lock pistol.

First created in Nuremberg around 1500, this weapon was originally designed for use in defending the walls of besieged of towns and cities. It could easily be fired from behind defenses, letting defenders shoot at besiegers on the ground below or when they were assaulting the walls.

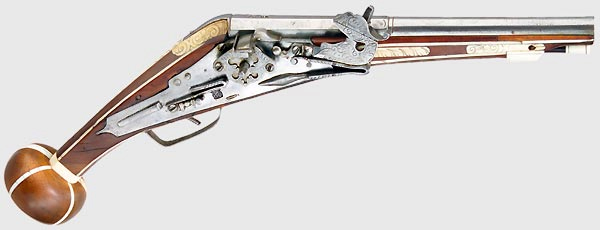

The firing mechanism on this weapon was far more sophisticated than that for matchlocks. A serrated disk was attached to a spring, which was held tightly wound inside the gun.

Pulling the trigger released the spring, causing the disk to spin. In doing so, the disk scraped against a piece of flint, creating sparks that ignited the powder in the gun.

Around a foot long, the wheel-lock pistol could be fired one-handed, making it perfect for cavalry. Mounted pistoleers would carry multiple pistols, riding to close range before firing them at opponents.

Manufacturing Centers

As the popularity of firearms grew, manufacturers started making them in large batches, ready to be sold to rulers and their armies.

Though the weapons were handmade, the employment of increasing numbers of armorers allowed mass production. Artisans who had previously made armor, swords, and other material of war turned their hand to guns.

In the early days, the major centers of production were spread across the continent. In the north, Augsburg and Nuremberg were important. In war-torn Italy, Bergamo, Brescia, and Milan supplied regional rulers and the mercenaries in their employ.

By the start of the 17th century, the focus shifted. The Netherlands, having long been a center of industry and commerce, became the leader in the arms trade. Amsterdam was the most important center, but others led in particular specialties – small arms and gunpowder from Delft and Dordrecht, saltpeter-infused match cords from Gouda.

Flintlocks and Beyond

The early seventeenth century also saw the emergence of a more sophisticated firing mechanism: the flintlock. A cross between the conventional trigger mechanism and the flint-on-steel striking of the wheel-lock, it meant gunners didn’t have to carry lit matches.

Read another story from us: The First Gunslinger: The Lone Gunman at Orleans

Over the course of the century, it replaced the matchlock, leaving something close to what we now recognize as a gun.

By 1700, the gun was king on the battlefields of Europe. All infantry now carried firearms of growing sophistication. It had taken several centuries of engineering, but the early handguns were now firmly in the past. The flintlock age had come.