The Battle of Little Big Horn is easily one of the most famous military conflicts of 19th century America. Books have been written about it, movies have been made about it, and historians have studied it for more than a century.

In North American jargon, people who are targets are “Custers.” When about to embark on a foolish move, a person might be asked, “Does the name Custer mean anything to you?” a line attributed to the late comedian Robin Williams.

But when examined seriously, the entire episode is one that lauds the bravery, skill, and smarts of the Native Americans who fought there. The only mitigating factor that one can offer Custer about his foolish decision to fight is that he was possibly given bad military intelligence before the battle.

By 1876, Native Americans were being badly treated by European settlers and herded onto reservations. Many Native nations, including the Lakota Sioux, Arapaho, and Cheyenne, did not take kindly to this treatment and felt betrayed by the treaties that clearly favored white men.

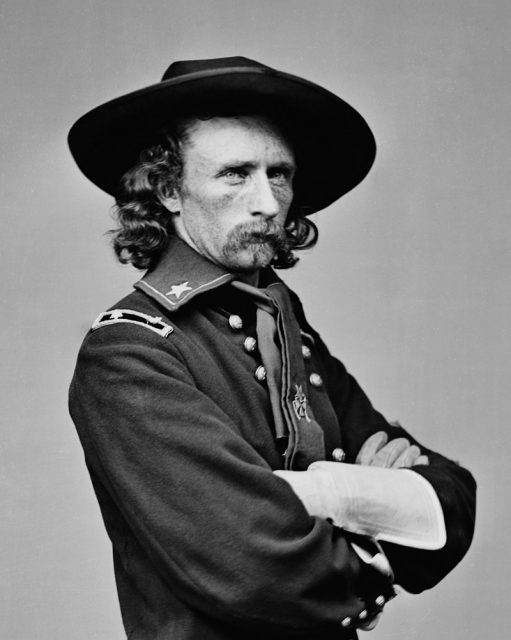

When they resisted going onto reservations, the U.S. Army was sent to “escort and persuade” them. Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer, of the 7th Cavalry of the U.S. Army, was asked by his superiors to head to Montana and hurry along the process of relocation.

They asked him to avoid unnecessary conflict, if at all possible. Many historians believe this was where Custer made his first mistake, as he decided not to arm his men with Gatling guns. But even if he had armed them, it’s doubtful the outcome would be different. Custer was badly outnumbered, outwitted, and was missing a key piece of information: the warriors were armed.

Custer sent out scouts and they reported that a Native village was set up near the Bighorn River. He debated his next move but, after rallying his men, decided to invade. He thought the Natives would either submit quietly and move along to the reserves or simply back off. They did neither.

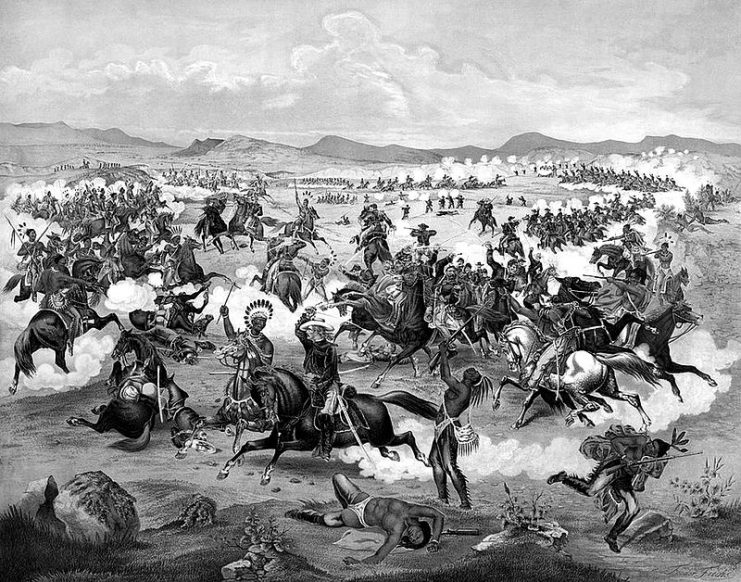

In addition, Custer found himself facing far more men than the original estimate of about 800 warriors. Some estimates put the number of natives as high as 2,500 since many nations had joined together under the leadership of Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse.

A “wild card” in the battle’s retelling is whether the Natives knew that Custer was coming and many people think this likely because their response was so organized. However, some experts disagree with that assumption. If the First Nations people did not know the invasion was imminent, that makes their victory even more impressive.

Custer divided his troops into three flanks commanded by himself, Commander Frederick Benteen, and Commander Marcus Reno. Custer sent Reno and his men to attack first. Some reports say that Reno had a drinking problem that made him incoherent and indecisive that day.

Whether true or not, he and his men were stunned by the Natives’ counterattack, which was forceful and overwhelming. Benteen followed in an effort to help Reno’s failing troops. He and his men tried desperately to quell the counter-offensive, but all they could do was dig in and wait for Custer.

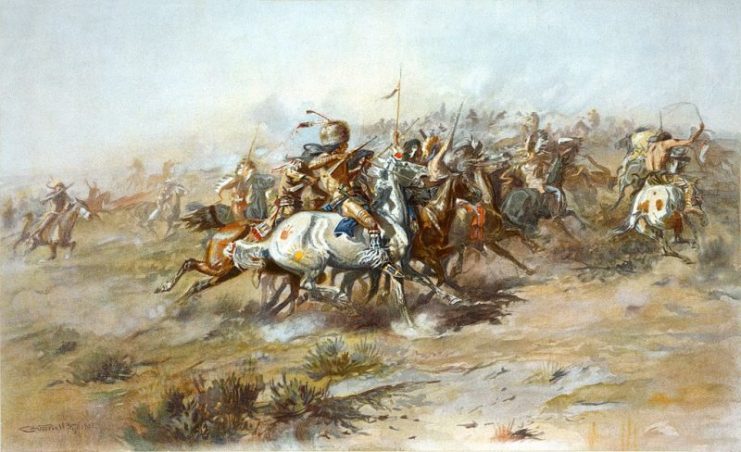

One of Custer’s favorite strategies was to attack head-on, and that is what he did at Little Bighorn. But the battle held no element of surprise and the Natives were ready for them, making this an inadvisable tactic. Two flanks of army soldiers had been efficiently dispatched by the opposing Natives already, and Custer’s attack on the village met with the same fate. Custer himself was shot in the chest and head.

Accounts of Custer’s last moments differ. This isn’t surprising since everyone experiences the chaos of war differently. Some said Custer died quickly, while others said he endured for an hour. But the fact is that “Custer’s Last Stand” as depicted in art, books, and movies is accurate on two key points: the battle was both poorly planned and executed, and it resulted in Custer’s death. He has been a prime example of bad military blunders ever since.