In the Spring of 1916, as WWI was raging in Europe, the students at Yale University’s class of 1918 were preparing themselves for a summer of relaxation before the next semester. One of those students, Frederick Trubee Davison, was looking across the ocean and knew that war would some come to the United States.

Creation

Davison saw it as his duty to serve his nation, but he was continually frustrated by the government’s inaction. By 1916, while public opinion had started to shift in favor of war, if very slowly, the US Government still held tightly to their policy of isolationism, hoping to avoid the bloody conflict altogether.

However, at sea more and more Americans were becoming the victims of German merchant raiding and submarine warfare, and something had to be done.

After speaking with the famous inventor John Hays Hammond Jr., and preparedness supporter Henry Woodhouse, Davison formed a plan. He would create a series of seaplane stations up and down the East Coast of the US, from which pilots would run submarine spotting patrols. The idea set the stage for the First Yale Unit and a significant development in US Naval Aviation.

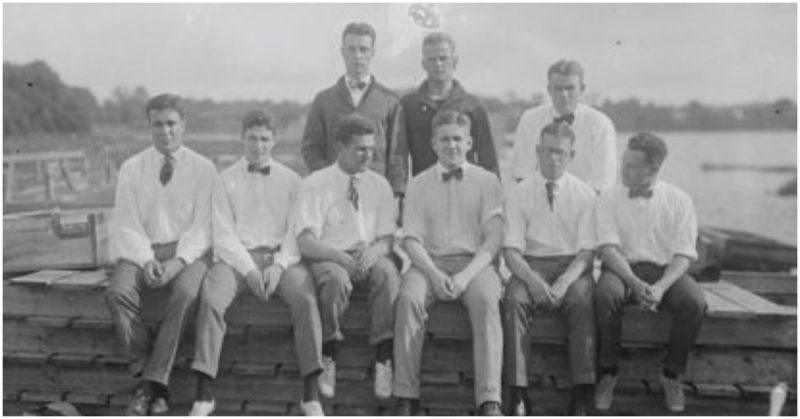

Davison and eleven of his classmates met at his family house in Peacock Point, Long Island. Under the tutelage of David H. McCullough, they began learning the basics of flight and were almost immediately hooked. Next came getting recognition from the Navy.

It was the most difficult challenge Davison had yet faced. Getting a training ground was easy as his family owned an estate. Funding for aircraft, fuel, repairs, and training was provided by his father, friends, and classmates. His persistent attempts at gaining official recognition, however, were met with denial. Josephus Daniels, the Secretary of the Navy, repeatedly refused.

The largest barrier was the US Government’s inability to accept private funds. Units like the First Yale Unit and the Aero Club of America were trying to be giving an opportunity to serve.

The second obstacle was the Navy’s apparently conflicted viewpoint on aircraft. One source regarded them as a toy while, in 1914, Josephus Daniels had argued that aircraft must become a part of the Navy’s force for both offense and defense.

Despite Secretary Daniels’ apparent fondness for aircraft, every attempt to receive official support failed. The US simply did not see the need at the time, and funding for a series of flying boat stations was not available.

Then on August 29, 1916, Congress passed an act establishing the Naval Reserve Flying Corps, and a precedent was set. Davison contacted John H. Towers, a famous pilot, and the third person to become a US Naval Aviator. He finally convinced Secretary Daniels to approve the First Yale Unit as part of the Navy Reserve.

Twenty-nine young Yale students were enlisted and sent to Palm Beach, Florida to earn their wings. Davison was made Lieutenant Junior Grade and given command of the Unit.

Those men were among the first one hundred Naval Aviators in United States history. They were ready to serve their nation, and all looked towards Europe. After a summer of training, the first two pilots left for Europe in August 1917, with two more following a month later.

Service

The pilots were divided between British and French aerial patrol stations. Their duties were to search for German U-boats and merchant raiders, to protect troop transport and the vital shipping lanes.

At Felixstowe, in England, the first casualty of those brave men Lieutenant Albert D. Sturtevant was shot down by German ace Friedrich Christiansen while protecting a beef shipment from attack.

Just the night before, the doomed pilot had remarked that he finally felt like he was at war, and he supposed they were all now at risk of dying. Sturtevant was well liked by his comrades, and his death was certainly a blow to all who knew him.

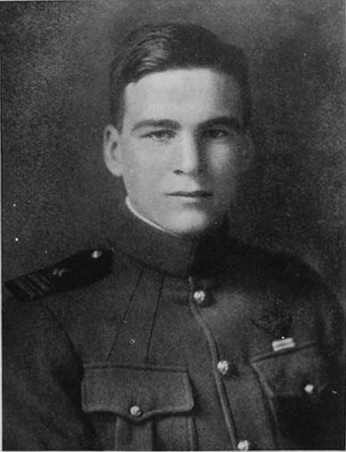

David “Crock” Ingalls became the only Naval Ace of the Great War. While serving with 213 Squadron, RAF, Ingalls earned a quick reputation for being bold, somewhat reckless, and forever cheerful. It was said he laughed during take off and combat just as much as he did when racing and often crashing, cars back home.

His bravado paid off, and in a matter of weeks, he had begun shooting enemies down. After racking up four kills, Ingalls was part of a balloon busting mission. Their purpose was to fire incendiaries into observation balloons, setting them alight and blinding the Germans.

On September 20, 1918, a few days into the mission, Ingalls’ engine gave out, and he began speeding towards the ground. He regained control, and coasted over the countryside, looking for a field to land in.

He knew he was well behind German lines, and would certainly be captured, and he dreaded the thought. By some stroke of luck, his engine sputtered back to life, and his Sopwith Camel roared back up into the sky. He was low on fuel, far behind German lines, and needed to get back home.

Avoiding enemy patrols and conflict he flew until over Visseghem when he spotted a lone Fokker D.VII. Diving on the German plane from behind, and taking the pilot by surprise Ingalls fired a burst of incendiary rounds into the aircraft, setting its stretched canvas and fuel alight. He was now an ace, but still miles away from safety. He nursed his plane back to his aerodrome and proudly reported his kill.

Those twenty-nine men from Yale, while wealthy students at a prestigious University back home, proudly and eagerly answered the call to the Great War. They combined their love of the water, adrenaline, and country into one of the founding units of the US Navy’s air wing. Their memory cannot be forgotten.