The bird was in awful condition, having been hit in the breast, lost one eye, gotten a bullet hole in her wing, and had a leg missing.

The hero of our story is a quite unusual one. When times were really tough for her battalion, she was their last hope. At the end of the day, she became their hero. With her persistence above everything, she saved the lives of 200 men—without a weapon in hand, armed only with instincts and speed. This hero didn’t even have hands. Her name was Cher Ami and she was a messenger pigeon!

Racing Messengers

The First World War was one of the greatest conflicts in which messenger pigeons participated. While by that time the telegraph had become a standard way of communication for armies, messenger pigeons were still in service. If a telegraph cable was cut or blasted by an explosion, pigeons would enter the scene.

However, not every pigeon was able to do the job of a messenger. Only a specific breed of racing pigeons was fit for the task. Known also as Homing Pigeons, these birds have an extraordinary ability to find their way home from great distances.

With a flying speed of up to 100 miles per hour, they were perfect for the task of delivering messages in war zones. Troops at the front lines of combat could rely on these pigeons to return straight to their bases and deliver messages.

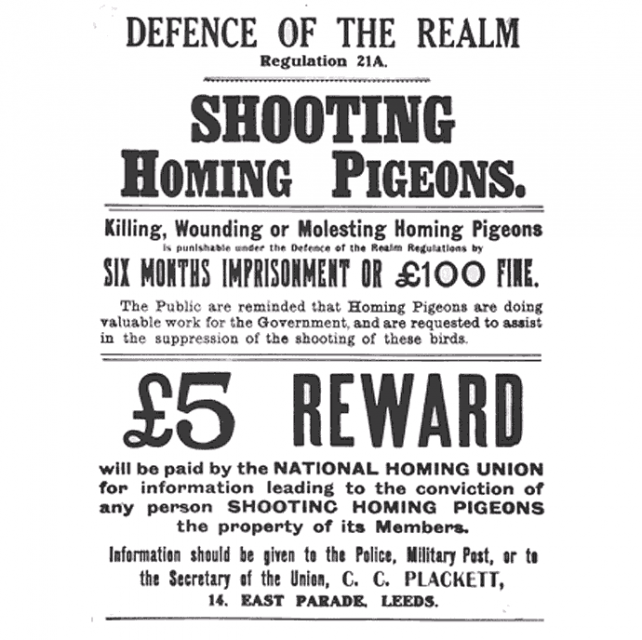

With such an important role, messenger pigeons were held in high regard. So high that during World War One, the British government punished anyone who even interfered with messenger pigeons with a fine of 100 pounds or six months of prison.

On the other side, and for the same reason, messenger pigeons were always a target for enemy riflemen. With every single take off, the pigeons had to face a barrage of fire from rifles and machine guns. It was a tough and very risky job. Cher Ami knew that best.

The Lost Battalion

Cher Ami, or “Dear Friend” was a messenger pigeon presented by the British to the US Army’s 77th Division. With most of the men coming from the city of New York, this division was popularly known as the “Metropolitan” Division.

It was another nickname, however, that made them famous. It was earned by nine companies of the division that found themselves trapped in the Argonne Forest. They were the “Lost Battalion.”

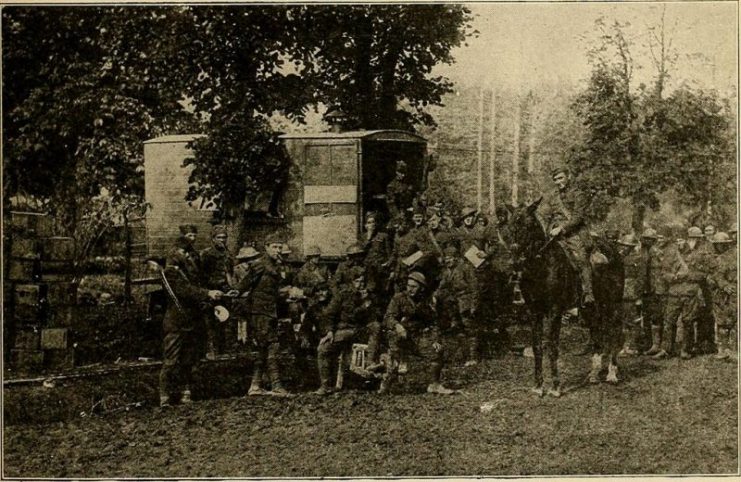

Members of the Lost Battalion getting their first meal at a regiment kitchen after the fight

On the misty morning of October 2, 1918, the 77th attacked German positions in the Argonne Forest as part of the large Meuse-Argonne Offensive. A series of such offensives were intended to give a final blow to the Germans on the Western Front. Orders were thus given not to retreat at any cost.

Under the command of Major Charles White Whittlesey, men of the 1st Battalion, 308th Regiment, 154th Infantry Brigade, 77th Division rushed into combat. By night, they reached their goal – the top of Hill 198. When they got there, they heard nothing but silence. There were no sounds of battle either to the left or to the right of their position.

As they soon figured out, there was no one to make a sound. The French troops on their left and American troops on their right flank had been suppressed by strong German resistance.

There they were, the men of the 308th Regiment along with parts of two other regiments, all alone in the gorge between two steep hills known as the Charlevaux Ravine. Germans were everywhere around them.

There was no retreat. Even if they wanted to, they couldn’t withdraw. So, what did they do? They dug themselves in and waited for help to come.

All Hell Broke Loose

On the following day, October 3, Germans attacked from all sides. The men in the Charlevaux Ravine, all 550 of them, were exposed to mortar fire, enemy snipers and machine gunners for the entire day. Major Whittlesey was determined to defend his position, even though he had no food or ammunition to do it. Without help from their command they were destined to be annihilated.

Back at the command there was confusion. Even though commanders knew that Whittlesey was exactly where he was supposed to be, it seemed that the artillery was unaware of that. At 2 a.m. on October 4, Whittlesey and his men received a barrage of friendly fire. Not only were the Germans pouring a rain of bullets on them, but their own artillery was bombing them as well.

Caught between two fires, Major Whittlesey was desperate to get the American bombardment to stop. As he run out of runners and communications were destroyed, he called in his pigeoneer Private Omer Richards. Whittlesey took a small piece of paper and wrote down a message: “We are along the road parallel 276.4. Our own artillery is dropping a barrage directly on us. For heaven’s sake stop it!”

As Private Richards was preparing to attach the tube with a message to a pigeon’s leg, a bomb exploded right next to him and the bird fluttered off.

Flight of the Hero

It was his luck that he had one pigeon more. It was Cher Ami. By that time she had completed 12 successful missions of delivering messages in the region of Verdun. This time, she was the last hope for the men of the Lost Battalion.

By the way she started her flight, it looked like all hope was gone. As soon as she left the trench, scared by the rain of shells, Cher Ami hid in a nearby tree. She was so scared and determined to stay hidden in that tree that Richards had to come out of his foxhole to climb the tree in order to chase her away.

As she finally left the tree and flew down the ravine, the Germans opened fire on her. They also knew what she meant to the surrounded soldiers. In a moment the focus of fire was turned from the American soldiers toward the flapping bird.

It was with agony in their eyes that the soldiers of the Lost Battalion were watching for Cher Ami to be hit and fall to the ground. To them, this was a moment of the greatest despair a man can experience.

Luckily, it was only a moment. In the blink of an eye, Cher Ami went higher into the sky, followed by a new barrage of fire. After a few seconds, the soldiers lost sight of her. The destiny of the soldiers trapped in Charlevaux Ravine was hanging wrapped around her leg.

Wings of Glory

It was October 4 at 3:30 PM in the messaging center of the 77th Division, 25 miles from the Charlevaux Ravine. The bell of pigeon loft number 9 rang.

A pigeoneer saw a pigeon covered with blood inside. The bird was in awful condition, having been hit in the breast, lost one eye, gotten a bullet hole in her wing, and had a leg missing.

A capsule with a message was hanging only by a leg tendon. As soon as the pigeoneer saw the message, he reported to his commander. As Major Whittlesey wrote in his report, at 4:00 pm the artillery fire stopped.

For four more days the soldiers of the Lost Battalion were on their own, fighting off German attacks. At least they had their own artillery on their side now. By the time reinforcements arrived on October 8, only 197 out of 550 soldiers had survived. The remnants of the Lost Battalion were saved.

Soldiers from the Charlevaux Ravine had no doubts that Cher Ami was their rescuer. After she delivered the message, she was taken to a field hospital, where surgeons made every effort to save her life. The hero from the Charlevaux Ravine survived, but lost a leg and one eye.

For heroism shown in battle, Cher Ami received the “Croix de Guerre” with Palm, one of the greatest French military awards. She lived for another nine months, and then succumbed to her combat injuries in Fort Monmouth, New Jersey. In 1931, she entered the Racing Pigeon Hall of Fame.

After death, her body was stuffed and stands today on display at the exhibition dedicated to American participation in World War I at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. It is a reminder that, no matter how tough things are, everyone can become a hero. Even the smallest living creature.