Not all heroes wear capes – and neither did all conscripted men in Britain wear uniforms. In fact, some of them were clothed in old rags for they spent most of the war (and a few years extra) working as coal miners for the Ministry of Defense, as coal was crucial for fueling the Allied war machine.

Between December 1943 and March 1948, ten percent of all male conscripts aged 18-25 were subjected to the so-called Bevin Program, which meant they served as coal miners for the war effort. Some 48,000 young men, most of them conscripts, and the rest volunteers, were sent to mines all across the United Kingdom, to perform manual work.

The creator of the program was a Labour Party politician called Ernest Bevin. It had been estimated that 36,000 men whose primary vocation was mining had been drafted and sent to fight in the war by 1943. A replacement for that workforce was desperately needed.

The British Government had to respond to the growing demand for coal and other raw materials in its fight against Hitler and his allies. In a speech given by Bevin on December 2, 1943, the then-Minister of Labour and National Service, told the men who were to serve their country by working in mines across Britain:

“We need 720,000 men continuously employed in this industry. This is where you boys come in. Our fighting men will not be able to achieve their purpose unless we get an adequate supply of coal.”

After his speech, all conscripts who were to replace the mining workforce were colloquially called “The Bevin Boys.”

A problem that plagued British industry was the lack of men who were willing to stay behind and wage their war on the home front. The general public was suspicious when they saw young men not in uniform, and so the Bevin Boys often risked being branded as cowards.

Due to this cultural phenomena, the selection process for the Bevin Program was conducted randomly. The Minister’s secretary pulled a number between 0-9 from a hat and performed the task every week during the war, beginning on December 14, 1943.

All men liable to be called-up that week whose National Service registration number ended in that digit were directed to work in the mines. It did not apply to men who were skilled in either flying an aircraft or who had experience with submarine warfare. The selection process also bypassed men who were physically unfit for such hard labor.

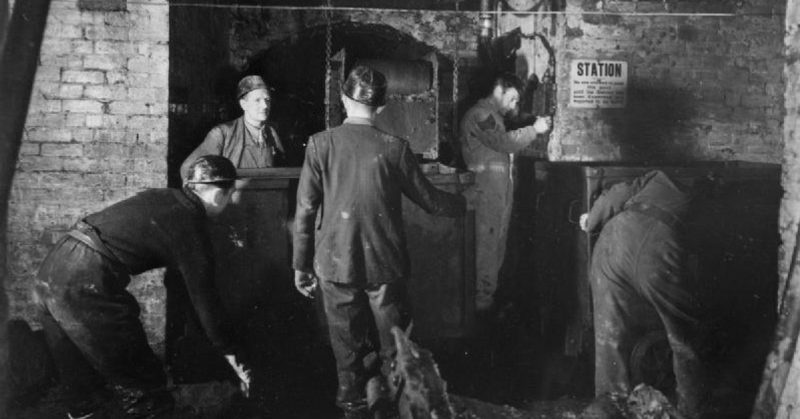

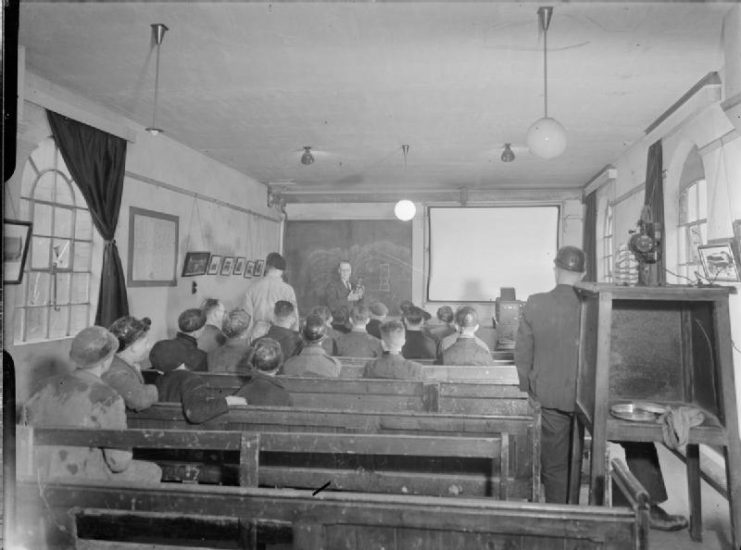

The men would then participate in a six-week training program, after which they were sent to their designated workplace. Bevin Boys were not supplied with uniforms but were encouraged to dress in old clothes as the work was extremely dirty. They worked in mile-long shafts together with conscientious objectors. In the 18th century, Britain had made it legal in specific cases to be a conscientious objector. Those men were obliged to work in an industry and often in the mines with the Bevin Boys.

Unfortunately, the Bevin Boys were for far too long perceived as able-bodied men who had dodged the draft, while that could not be further from the truth. As previously explained, the men were regularly conscripted, and their part in the war effort was indeed crucial.

In addition to this, their service lasted almost three years after the war, as a fatigued Britain needed to get back on its feet and needed all the help it could muster.

The Bevin Boys never received medals for their service and were considered by the public almost as convicts who were doing community service.

It was not until 1995, 50 years after the end of the war, that Queen Elizabeth II commemorated the men who had worked in the dangerous mines all over the country to ensure there was no shortage of coal for the war effort in those desperate times.

Since then, there have been some cases in which the Bevin Boys were mentioned and shown gratitude for their contribution by a government official. In 2007 a Veteran Badge was introduced, to reward the surviving participants of the program, and a memorial was erected in 2013 to commemorate their service and clear their name once and for all.