Prasutagus, King of the Iceni (an independent Brythonic tribe), had secured freedom for his family before his death. However, his will was ignored. His wife Boudicca was flogged, and his daughters were raped. Camulodonum, the Capital of the neighboring tribe, known as the Trinovantes, was occupied and turned into a Roman military camp.

To continue massive construction projects, the Roman government levied heavy taxes against the Iceni and their neighbors. Among the projects was a temple to the late emperor Claudius in Camulodonum. In 60CE, the Iceni revolted, led by their Queen, Boudicca. The Iceni were allied with their neighbors the Trinovantes.

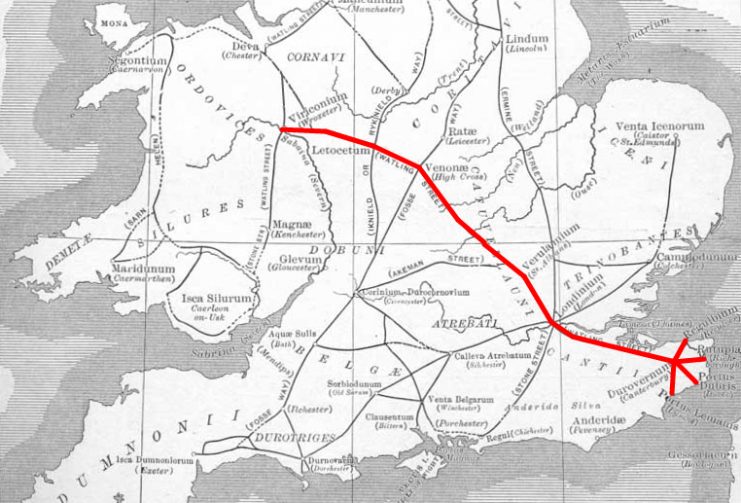

They sacked Camulodonum and burnt London to the ground. As they proceeded from St. Albans up the Roman road known today as Watling Street, they met an army of hastily assembled Roman soldiers, led by the local governor, Suetonius Paulinus.

The Location of the Battle

The exact location of the battle is not known. One source places it near Mancetter in Warwickshire, and this is not unreasonable, given the similarities to the terrain described in Tacitus’ account of the battle.

The Forces

Paulinus’ command consisted of roughly 10,000 Roman soldiers. This included not only the vaunted professionals-the legionaries-but local auxiliaries as well, including some cavalry. Roughly eighty percent of his force consisted of infantry, a fact which definitely played into his favor in the battle to come.

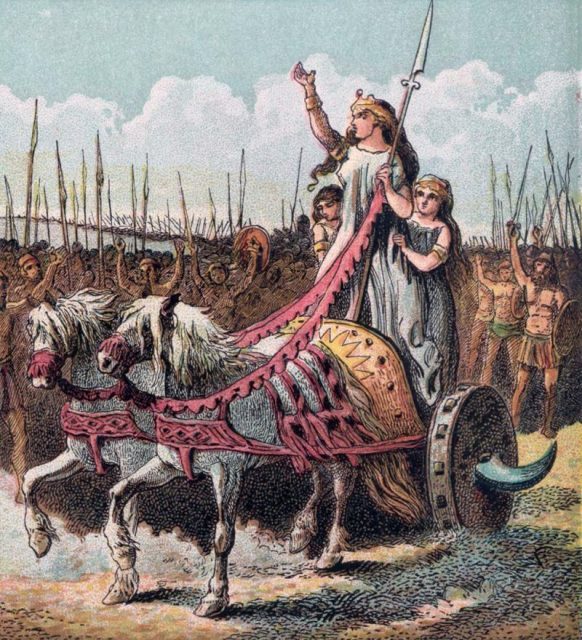

The size of the British army is not known, but Cassius Dio gives the staggering estimate of a quarter of a million. Whether or not this is the inflation of a propagandist is not certain. The Romans were certainly outnumbered, by at least three to one. The majority of the army fought on foot. The Queen, however, led her army from her chariot.

The Terrain

The Terrain upon which Paulinus chose to fight the battle was crucial. He needed to mitigate the numerical superiority of his enemies, otherwise, his soldiers would be surrounded and slaughtered. Therefore, he chose a narrow gorge which emptied into an open plain. Mirroring the Spartans at Thermopylae, he hinged the battle’s outcome on the superior training and discipline of his soldiers.

The Britons, having won an easy victory against the Roman ninth legion earlier that year, were convinced that the battle would be easily won. They placed their supply wagons in a concave ring facing the gorge. This line of wagons was packed with spectators, likely the families of the warriors.

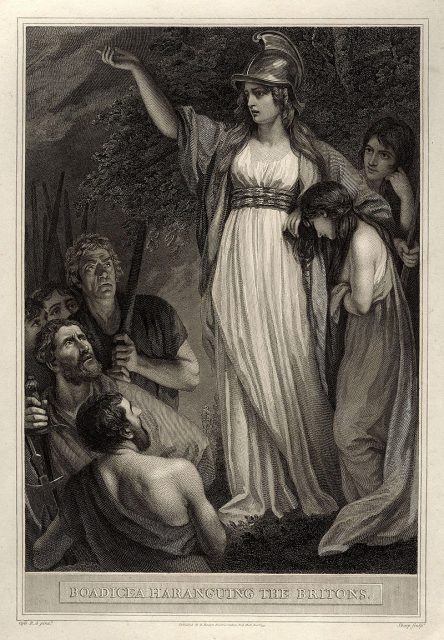

Charismatic Leadership

The leaders of both sides are said to have given speeches before the battle to bolster their warriors’ morale. According to Tacitus, the Queen of the Iceni listed the depredations of the Romans and stated: “Win the battle or perish, that is what I as a woman will do. You men can die as slaves if you like.” It had to have been quite clear that the rebellion was motivated by revenge as well as liberation.

Paulinus is said to have been much less heroic in his speech, stating that “There were more women… than men” and their enemies were “not even soldiers…” The speech was documented by Agricola, a member of Paulinus’ staff.

The Britons Charge

The Britons then charged into the gorge. They lacked the discipline of the Romans; instead, they launched themselves forward in a wild rush. Their style of warfare relied on the impetus of this charge to break the enemy formations.

What cohesion may have existed was quickly broken by the shower of pilum, or heavy javelins, which the Romans sent into their ranks. These were meant to bend on impact, thus rendering shields into which they had become lodged unusable. Many of the Britons possessed little protective equipment other than their shields, which placed them at a disadvantage against the Roman legionaries.

The Romans Exact Their Revenge

At this point the Roman Legions advanced, having thrown their javelins. They pushed forward in ordered ranks, stabbing with their swords from behind their large shields. The Cavalry began to attack the flanks of the Britons. They could not stand up to this advance and fled back to their wagons. However, they were trapped against this barrier. Once they had defeated the British warriors, the Romans climbed over the wagons, and according to Michael Wood, “[they] must have gone mad with bloodlust.”

It is said that as many as 80,000 Britons died that day, while Roman casualties numbered under 1,000. The Romans did not spare the spectators, and many women and children were among the dead.

Read another story from us: 9 Reasons Why Boudica Almost Beat the Romans

The Aftermath

According to Michael Wood, after this defeat, Queen Boudicca poisoned herself, fearing the humiliation of capture by the Romans. Due to his successes at Camulodonum and London, Emperor Nero replaced Paulinus as governor, fearing that his harsh policies would provoke further rebellion in Britain. No further serious threats to the Roman occupation of Britain would arise until the Romans abandoned the island in the early fifth century.