Also known as the Dardanelles Campaign, the Gallipoli Campaign, or the Battle of Çanakkale, was a failed attempt by the Allied forces to capture the Ottoman capital of Constantinople, through the Gallipoli peninsula. The battle took place during World War One, it began on 17th February 1915, and lasted for 10 months, 3 weeks and 2 days, involving British and French forces alongside the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC).

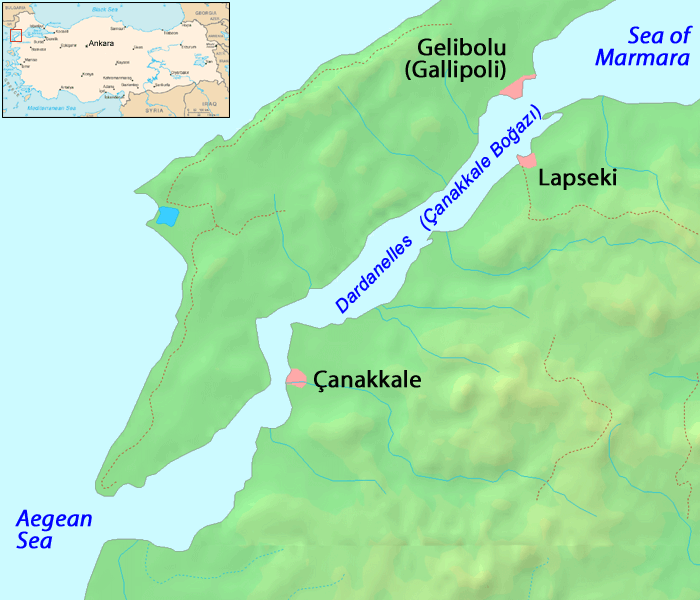

The Gallipoli peninsula was located north of the Dardanelles, a strait that linked the Russian empire to Europe.

By the end of the campaign on 9th January 1916, the Allied Forces had suffered heavy casualties and had to be evacuated from the peninsula.

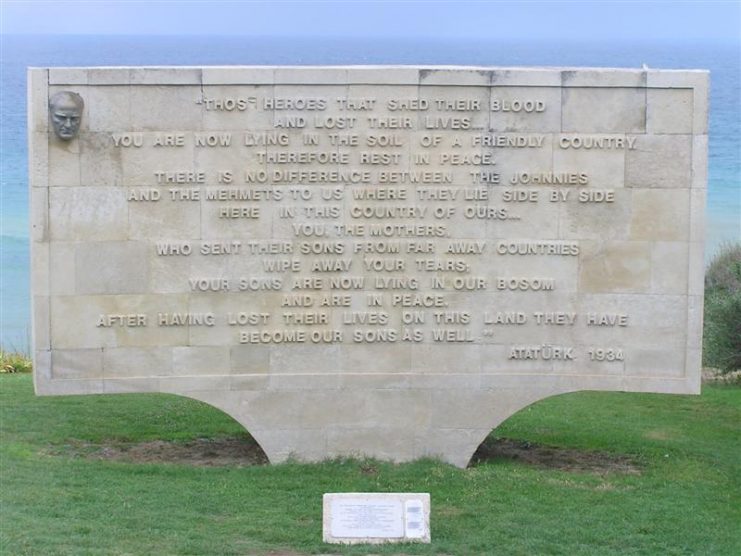

The failure of the Allied Forces invasion of the Ottoman region marked the only major victory of the Ottoman Empire. The struggle formed the foundation for the Turkish War of Independence, which ended eight years later, with the declaration of the Republic of Turkey.

While the war on the Western Front was being stalled, the Allied Powers were considering launching campaigns in other regions of the conflict, rather than continuing with the counter offensive at the First Battle of Marne and First Battle of Ypres which ended with the British suffering massive casualties.

Following the Ottoman entry into World War One through Operation Black Sea in which they bombed the port of Odessa and sank several Russian ships, the Russian empire came under more pressure as the Ottoman forces launched the Caucasus campaign.

Also, after the Ottomans entered World War One, they sealed off the Dardanelles which was the last route for movement of supplies after every other route through the White Sea, Baltic Sea, and overland trade routes between Britain, France and Russia had been closed by the German forces and their allies.

France’s initial suggestion to attack the Ottoman Empire was rejected, and Britain’s attempt at bribing the Ottomans into joining the Allied side failed. When Grand Duke Nicholas of the Russian empire called for help on January 2, 1915, requesting assistance with combating the Ottoman offensive in the Caucasus, Britain easily accepted.

Plans began for a naval demonstration in the Dardanelles. They would invade the Ottoman Empire, while at the same time forcing Ottoman troops to return from the Caucasian theatre.

However, there were major setbacks in the plan: The Allied powers had insufficient knowledge about the terrain, and worse, the Ottoman troops were highly underestimated.

On the 17th of February 1915, the expedition began. A British seaplane from the HMS Royal Ark Navy went on a recon mission over the Straits, and on the 19th, a strong Anglo-French task force launched a long-range bombardment of Ottoman coastal artillery batteries in Dardanelles.

The British had originally intended to make use of 8 aircraft for the bombardment but these were unusable due to very poor weather conditions. However, by 25th February, the outer forts have been cleared, and mines removed.

After the initial headway, the Royal Marines were deployed to capture and destroy the guns at Kum Kale and Seddülbahir. The naval bombardment, on the other hand, shifted to the batteries between Kum Kale and Kephez.

The mobility and evasiveness of Ottoman batteries was a cause of frustration for the Allied forces, this was evident as Winston Churchill began mounting pressure on the naval commander to double the efforts of the navy. This prompted Carden to draw up fresh strategies with plans of invading Constantinople in two weeks.

During this period, a wireless message was intercepted by the Allies. It was revealed through the German message that the Dardanelles forts were running low on ammunition and were gradually yielding to the Allied bombardment. The sense of victory was heightened, and a plan was drawn up to strike on 17th March.

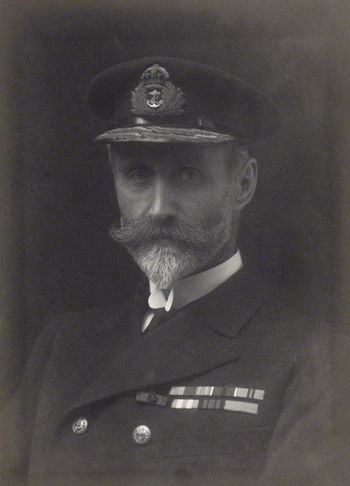

However, before the attack began, Admiral Carden suffered a nervous breakdown and was replaced by Admiral John De Robeck.

On March 18, 18 Allied battleships with an array of cruisers and destroyers began the attack on the Dardanelles. The Ottoman’s defense was fierce. The Allied fleet came under heavy return fire, causing damages to the ships.

Minesweepers were sent along the Straits, but they were forced to retreat under heavy Ottoman artillery fire. A French battleship, Bouvet capsized after striking a mine, sinking with over 600 crew members aboard.

A total of 3 ships were sunk, while another 3 were damaged. This forced Robeck to recall the expedition, in a bid to save what was left of his force.

In the wake of the failed attack, another one was planned. This time, it would be a land invasion. Preparations began for a large-scale landing on the Gallipoli Peninsula. Troops from Australia, New Zealand, and the French colonies joined the British forces on the Island of Lemnos, in the northern part of the Aegean Sea, under the command of General Ian Hamilton.

On the other side of the battle, Ottoman forces were being fortified under the command of German general Liman Von Sanders. Sanders positioned Ottoman troops along the shore, where he expected the Allies to land.

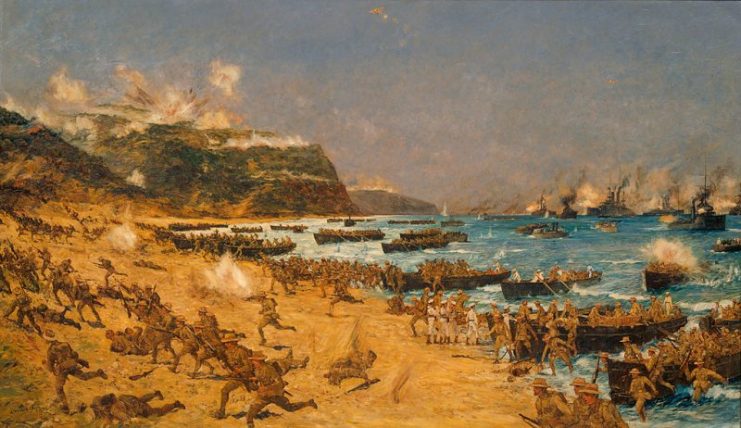

On the 25th day of April, the Allies began the invasion of the Gallipoli peninsula. They succeeded in establishing two beachheads at Helles, the southern tip of the peninsula, and at Gaba Tepe, on the Aegean coast. However, they suffered heavy casualties.

Following the establishment of their beachhead, Ottoman forces launched a counter-offensive in a bid to force the Australian and New Zealand troops back into the sea. They suffered heavy losses with the intervention of British ships and aircraft. The Ottomans suffered 13,000 casualties, out of whom 3000 men died. The Australian and New Zealand casualties were 628, out of which 160 were killed.

Gaba Tepe would be renamed Anzac Cove, in honor of Australian and New Zealand troops who gave their lives while fighting to establish the beachhead there.

The casualties on the Ottoman side were so intense that a ceasefire was temporarily organized by Aubrey Herbert to bury the dead soldiers lying in no man’s land.

The Allies were able to make little progress, but the Ottoman reinforcements from both Palestine and Caucasus fronts made things increasingly difficult. In a bid to break the stalemate, the Allies launched another landing at Sulva Bay on August 6th. The troops at Anzac cove made a diversionary advancement northwards while those at Helles took diversionary actions.

The Landing at Sulva Bay met no serious opposition, but a moment of indecision cost them as Ottoman reinforcements caught up with them and stalled their progress.

With the number of Allied casualties towering, Hamilton petitioned Lord Kitchener, the British War Secretary for a reinforcement of 95,000 men. Kitchener was unable to deliver up to half that number.

The failures at Gallipoli sparked several opinions from the public, with Hamilton being at the center of it all. He was later recalled and Sir Charles Monro was put in his place. Monro would shortly begin requesting evacuation of the troops.

In early November, Kitchener came to the peninsula and finally approved Monro’s request that the remaining 105,000 troops should be evacuated.

The evacuation began at Sulva Bay on 7th December, with the last troops being evacuated on the 9th of January 1916, bringing the campaign to an end.

About 480,000 allied troops took part in the campaign, suffering more than 250,000 casualties with 45,000 soldiers dead.

Also, the Gallipoli campaign sparked some serious political repercussions. It saw the resignation of Lord Fisher, who disapproved Churchill’s move for the Gallipoli campaign. Winston Churchill also resigned from government after the failure and went on to command an infantry unit in France.

The Evacuation of Gallipoli, The Brilliant End To A Disastrous Campaign

Several historians are of the view that the performance of the Allies in the campaign was plagued by over-confidence, poor planning, unclear goals, poor equipment, and logical and tactical deficiencies.