“Shrapnel” is a term that did not originate in WWI, but which was certainly popularized by the war.

For better or worse, the First World War forever changed the way that subsequent wars would be fought, and profoundly affected international relations between a number of prominent world powers – but it has also had a lasting impact on less obvious aspects of human existence, such as language.

Many terms that either had their origin in the trenches of the First World War, or were popularized and the brought into the civilian lexicon by the servicemen who fought in the war, are words we still use today – words like “basket case,” “cooties,” “strafe,” and a number of others.

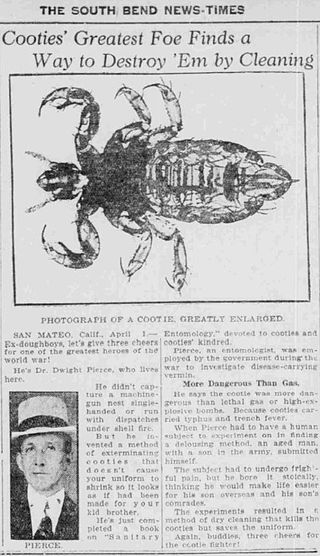

“Cooties,” for example, is a term we now associate with kids and playgrounds, but the origin of the phrase was a little darker than mere childhood slang. The trenches of the First World War were, among other things, quite filthy and unhygienic places, and parasites of all sorts thrived there.

Head and body lice proliferated in the trenches, and rare was the soldier who did not get at least one infestation of “cooties” – as the lice came to be known – during his time on the front.

It is thought that the word either came from the Malay word “kutu,” which means louse, or from earlier British regional slang in which the term “coot” was used to describe a type of waterfowl that was associated with parasites.

“Basket case” is a term that saw widespread use in the 20th century, particularly in the ‘80s and ‘90s, popularized by teen movies such as The Breakfast Club or through songs like Green Day’s Basket Case. The actual origin of the term is very dark, however.

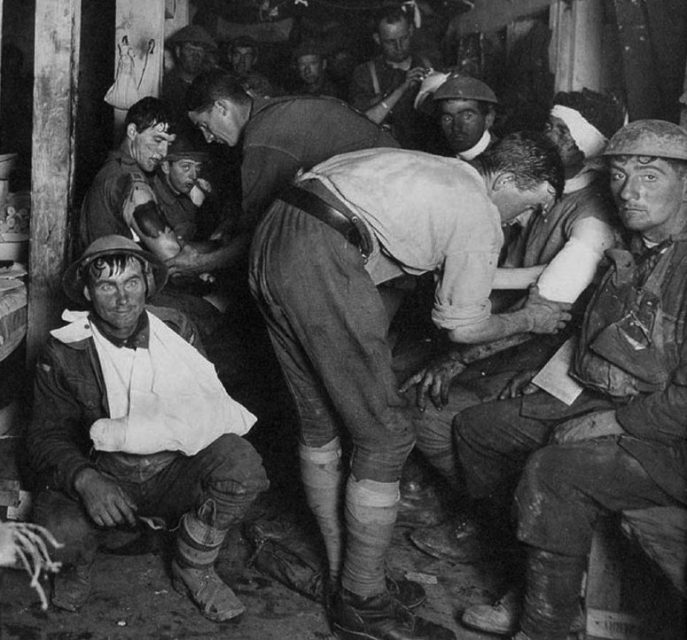

During WWI, the term “basket case” was used to describe troops who had to be transported from the battlefields in baskets rather than stretchers, due to all four of their limbs being blown off (which would mean that they would likely roll off a standard stretcher).

However, in 1919 the Surgeon General to the US Army issued a press release stating that no such “basket cases” existed, and the stories that men had had all four limbs blown off (and survived) were merely rumors. Nonetheless the term stuck, although its meaning changed quite drastically over the decades following the war.

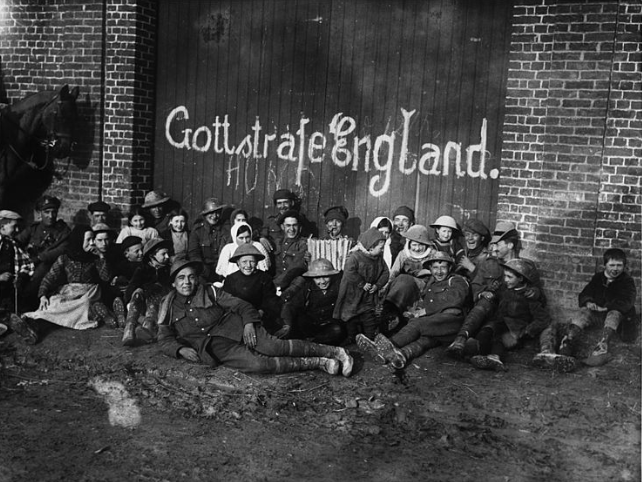

“Strafe” is a word that is popular in both military parlance and video gaming-speak. It is another word that had its origin in the First World War, but it did not come directly from the English-speaking troops.

Instead, the word is directly lifted from German, in which it means “punish.” This was because the phrase “Gott strafe England!” (“God punish England!”) was widely used in German propaganda posters.

English-speaking Allied troops soon began using the word “strafe” in a mocking sense, to make fun of the German propaganda. Soon its meaning shifted, and it began to be used to describe various types of assault, often those involving machine guns. Toward the end of the war it began to be most often used to describe the action of firing a machine gun from a low-flying aircraft.

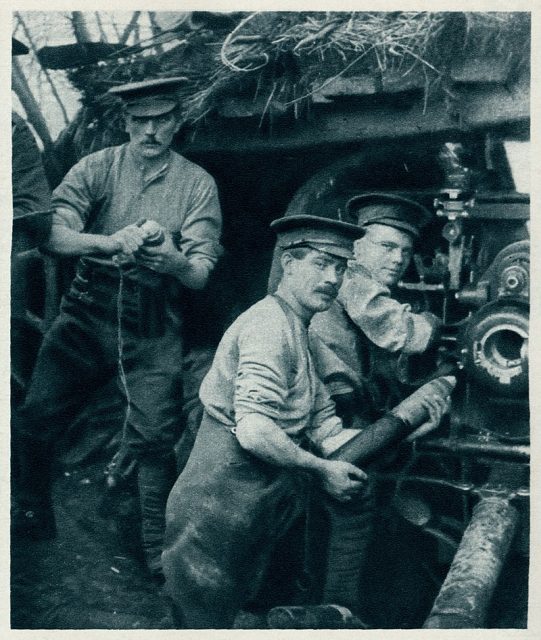

“Shrapnel” is a term that did not originate in WWI, but which was certainly popularized by the war. It also had its original meaning changed by the many people who used it during WWI to the extent that the meaning of the word actually changed. While “shrapnel” is now understood to mean pretty much any fragment of a bomb or an explosive shell, prior to WWI this was not the case.

“Shrapnel” was actually a very specific type of anti-personnel artillery shell that exploded in mid-air, blasting out lead balls, invented in 1806 by British General Henry Shrapnel. During the First World War, the word saw widespread use as a catchphrase to describe any bomb or shell fragments, and this meaning has stuck.

Finally, another word that comes directly from the First World War that everyone, especially anyone with an interest in anything military knows, is the word “tank.” The word and its origins are far older than WWI, of course, but the use of the word to describe a heavy armored vehicle – now one dictionary definition of the word – did come from WWI.

The British were the first to develop tanks, and this was a project they shrouded in secrecy. To prevent information about the battlefield vehicles they were developing being leaked, they decided to give the vehicles a codename. At first the totally innocuous term “water carrier” was suggested, but this was soon changed to the equally innocent-sounding word “tank.”

When these vehicles, these “tanks,” first rolled onto the battlefields of WWI in 1916, though, they were anything but innocuous. For whatever reason the codename stuck, and the word “tank” gained a completely new meaning.

There were also a number of stranger terms that were used widely during the war, but which fell out of use quickly after it was over. “Doolally” meant insane or crazy, while a “poodlefaker” was a playboy or an excessively vain man.

“Pear drops” was a term used as slang for poison gas, rather ominously because of the smell. “Gaspers” were cigarettes, but this term was mainly used by officers rather than enlisted men.

Read another story from us: “Taking Flak” & Other English Expressions That Have Their Origins In WW2

While some terms that were widespread during the First World War have faded from general use, many seem to have stuck and show no signs of dropping out of use any time soon. So, as you go off to do whatever you need to do, remember to wash your hands to keep the cooties away, watch out for shrapnel when seagulls are flying overhead, and don’t let life get to you so much that you become a basket case!