Most battles are mental challenges carried out by physical forces, wherein a commander must solely focus on how to acquire superiority over the enemy.

But sometimes there is another element, that commanders have to prove themselves to others. Such was the case during the North African theater of World War II in 1943.

“Hill 609,” an otherwise-nameless, well-protected death factory of a hill, represented redemption for the American soldiers and their commander, Major-General Charles Ryder.

The British had been in North Africa since 1940, squaring off against both the Germans and Italians in the region. When they were joined by the Americans in late 1942, they were naturally a little skeptical of the abilities of this newest addition in the war.

Immediately, relations between the American forces and the British were tense. The British thought of themselves as the old guard – scions of an imperial age, a centuries-old global power steeped in warfare and conquest, and well entrenched in their war with the Axis.

The Americans, in contrast, were new and untested. Even despite the Americans’ superior resources and well-trained troops, the British had reservations about their worthiness. These tensions spilled over in spring of 1943 to every level of the military, and they were threatening to poison the efforts of the campaign.

The 34th Infantry, under the command of Major-General Charles Wolcott Ryder, was the first American division deployed to North Africa. Ryder was born in 1892, and graduated the US Military Academy in 1915.

He’d not only seen action in the first world war, but also been awarded two Distinguished Service Crosses, a Silver Star, and a Purple Heart as both a major and a colonel during that conflict. This was no shrinking violet, and no inexperienced grunt.

In November 1942, Ryder led an Anglo-American force of 33,000 men in Operation Torch, taking Algiers in the amphibious assault that would kick off Anglo-American joint operations.

While the mission was a resounding victory there were also some setbacks, and they would set the stage for more conflict between the two armies.

For some, Ryder would never shake the association with these failures and difficulties, although they were no real reflection on his ability.

He enjoyed the full confidence of Major-General Omar N. Bradley, a fellow West Point graduate, and General George S. Patton’s deputy. But even as he had friends in high places, he also had his fair share of detractors.

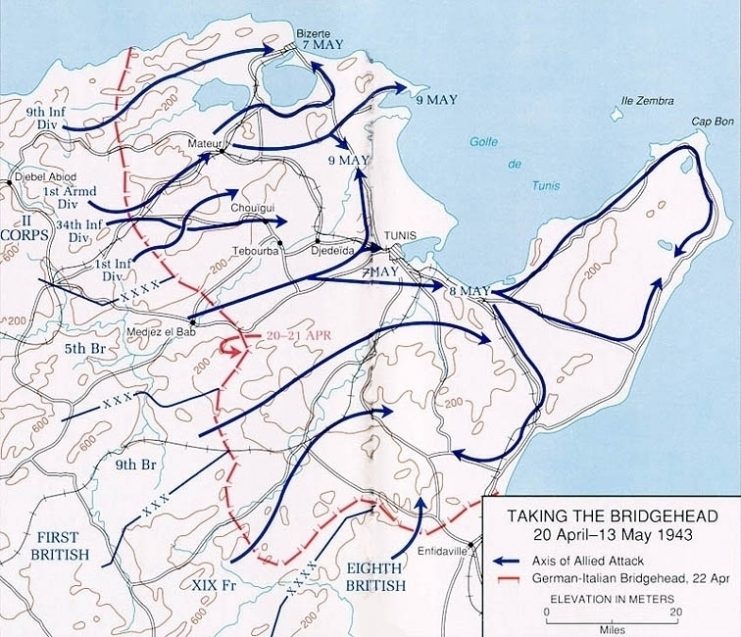

The Axis was on the run in North Africa in March 1943. The fighting at Wadi Akarit on March 6-7 had turned out badly for them, and they were forced to retreat to Endifaville, some fifty miles from Tunis.

This presented the Allies with an opportunity. Lieutenant-General John Crocker of the British Corps realized that if they could punch through at Fondouk, they could effectively cut off any Axis line of retreat.

The task fell to Ryder and the American 34th Infantry to take the pass. Ryder wanted to use encirclement to take Fondouk, but Crocker disagreed and ordered a frontal assault. The consequences were disastrous.

The 34th took heavy casualties in Crocker’s assault and didn’t take the pass. Naturally, Crocker blamed Ryder for failing to complete the plan, and ordered the Americans away from the front lines for retraining.

Humiliated, Ryder and his 34th Infantry withdrew. By this time, the Americans were tired of the patronizing attitude of the British brass, and saw Crocker’s forced withdrawal of Ryder’s forces as yet another example of this behavior.

Worried that the withdrawal would adversely effect not only the 34th’s morale, but the morale of the whole of American forces, Ryder and Patton appealed the decision.

Ultimately, General Sir Harold Alexander, the British commander of the entirety of the ground forces, agreed with them and overruled Crocker. Ryder and the 34th Infantry stayed in the field.

That didn’t end the arguments brewing between the British and American commanders. Patton thought the problems at Fondouk were due to a lack of close air support, while Air Marshall Arthur Coningham believed that the troops themselves were inadequately trained and unfit for battle.

This line of argument continued until General Dwight Eisenhower himself arrived to conclude it, forcing Coningham to apologize to Patton.

Yet throughout this high-level bickering, there were still unanswered questions regarding American efficacy. The first trial by fire had been an unmitigated disaster, and both Ryder and the Americans now had to prove themselves.

The Axis forces had been held at the edge of the Tunisian peninsula, and it was time to finish them off. The Americans were only given a minor role at first, prompting Bradley to go to Eisenhower, who then suggested to British General Harold Alexander to let the Americans assume the risk of taking Bizerte.

To get to Bizerte meant taking Hill 609, one of the best defensive positions in Tunisia. It was also the location of German General Jürgen von Arnim’s Afrika Korps, who had been using its heights to both observe and blast away at the Americans using heavy artillery.

It took three days for the 34th Infantry Division to take Hill 609 in April 1943. They took it despite heavy casualties, and then turned around to face fresh hell in the form of German counterattacks, which sought to take back the hill before the 34th could even establish suitable defenses.

Read another story from us: Life of General Patton in 50 Pictures

Charles Ryder and the 34th Infantry held that hill, restored their glory, and opened up the road to Bizerte. It had been a long, hard road to achieve their welcome, but they were now represented in full force in the African campaign.