“they shot any man, woman, child, cow, hog, or just about anything that moved. Before burning the town they thoroughly looted it.”

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, is one of the most well-known events of the Second World War. Less well-known is the Doolittle Raid, in which American B-25 bombers bombed the Japanese cities of Tokyo, Nagoya, Osaka, and Kobe on April 18, 1942, in response to Pearl Harbor.

Tragically, the Japanese reprisal for the Doolittle Raid – the Zhejiang-Jiangxi Campaign – is barely remembered today, even though it cost 250,000 Chinese civilians their lives.

After the shock of the unexpected Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor had worn off, the United States decided to strike back at Japan.

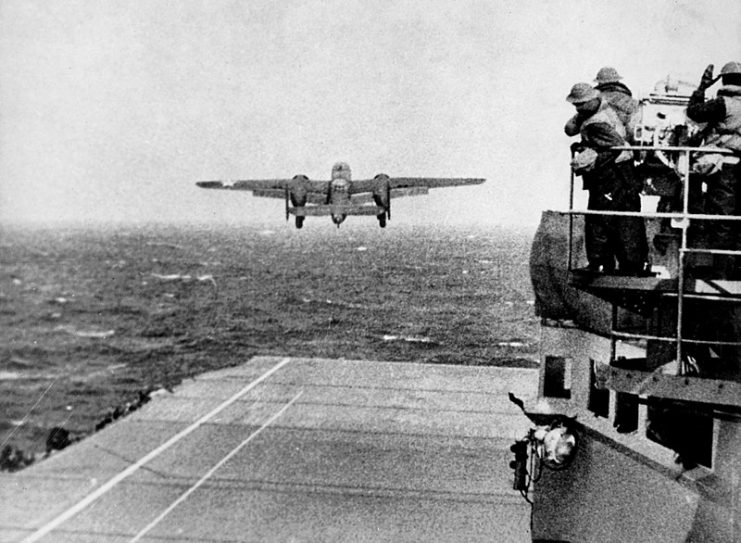

Lieutenant-Colonel James Doolittle of the United States Army Air Force (USAAF) devised a daring plan to strike at the Japanese home islands by launching B-25 bombers from Navy aircraft carriers, which had never been done before.

On April 18, 1942, Doolittle led the raid on the Japanese homeland, bombing a number of Japanese cities with 16 B-25 bombers. The raid, totally unexpected by the Japanese, was a success. Most of the bombers, after passing over Japan, landed in the Chinese provinces of Zhejiang and Jiangxi.

Much of China was occupied by Japan at this time, and as a result of the brutality of their invasion, the Japanese occupiers were much hated by the Chinese. Consequently, local Chinese peasants helped many of the American airmen after they crash-landed their bombers on Chinese soil.

https://youtu.be/k0l1RTiSnaU

The Japanese response to the Doolittle Raid was swift and brutal. In a campaign called the Zhejiang-Jiangxi campaign, 180,000 troops of the Japanese Army’s China Expeditionary Force set out not only to find the American airmen but also to punish anyone they suspected of aiding them in any way.

What followed was on a par with the Rape of Nanjing in terms of violence, bloodshed, and savagery. Japanese troops swept through the provinces of Zhejiang and Jiangxi. They managed to capture eight US airmen, of whom they executed three. The worst horrors, though, were suffered by the Chinese civilian population.

When Japanese troops arrived in a town or village in Zhejiang and Jiangxi, they presumed guilt and complicity with the US airmen on the part of the entire village. This applied to men, women, and children all the way down to domestic animals, regardless of whether any US airmen had even been anywhere near the settlement.

The sentence the Japanese troops imposed for this crime of suspected complicity was death.

The atrocities committed en-masse by the Japanese forces were witnessed by a number of foreign Christian missionaries who lived in some of these villages and towns. One, Father Wendelin Dunker, described the Japanese horrors with chilling clarity:

“they shot any man, woman, child, cow, hog, or just about anything that moved, they raped any woman from the ages of 10 – 65, and before burning the town they thoroughly looted it.”

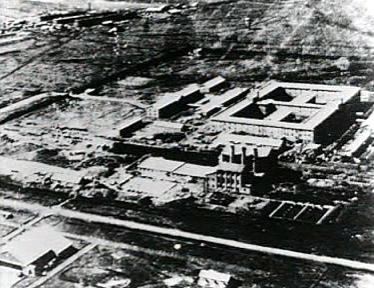

On June 11, the Japanese troops moved from villages and small towns to the city of Nanchang which had a population of around 50,000.

After surrounding Nanchang so that none of the inhabitants could escape, they took the city in an orgy of bloodshed, rape, murder, and looting. The Japanese troops rounded up 800 women and imprisoned them in a warehouse, in which they were repeatedly raped. Men were summarily killed on the streets, and the city was looted.

The Japanese occupied the city for around a month in a reign of barbarous violence and horrific bloodshed and brutality, before burning the entire city down. The process of burning Nanchang took three days; the troops wanted to make sure that they left nothing of it standing but charred rubble.

Other towns and cities in these provinces were taken in a similar fashion, with the Japanese troops laying waste to everything and conducting a campaign of wanton terror, destruction, and looting. In some regions, eighty percent of all homes were destroyed, and the majority of the population were left destitute.

The Japanese troops who participated in the Zhejiang-Jiangxi campaign did not stop at rape, torture, and murder, though. In August, members of Japan’s secret biological and chemical weapons division, Unit 731, attacked the region in a more insidious but equally devastating manner.

Realizing that once they had left the area, it would be reoccupied by both Chinese troops and civilians, Unit 731 poisoned wells, springs, and water sources with cholera, typhoid, dysentery, and paratyphoid bacteria. They also infected food and water rations with these pathogens, leaving them where hungry Chinese troops and civilians would find them.

They even released plague-carrying fleas into the fields.

All in all, it is estimated that 250,000 Chinese civilians lost their lives in this campaign of wanton brutality and bloodshed. Yet another tragedy of the Zhejiang-Jiangxi campaign was that few of the troops and officers involved were ever prosecuted for the egregious war crimes that were committed during this campaign.

Read another story from us: Operation K, the Second Attack on Pearl Harbor Kept Secret for Decades

Field Marshal Shunroku Hata, who orchestrated the campaign, was convicted of war crimes and sentenced to life imprisonment but was paroled in 1954.

Perhaps equally sadly, this campaign of terror has largely been forgotten in the West’s remembering of the Second World War.