In 1530, the Knights Hospitaller were given control of the island of Malta. 35 years later, in 1565, the Ottoman Empire invaded the island. The Hospitallers drove them off during a siege that lasted over three months. Crucial to the Hospitallers’ success were the defenses they had built on the island. So what did they do to fortify it?

Reinforcing the Existing Defenses

The first thing the knights did after gaining the island was to reinforce the defenses built by the previous owners.

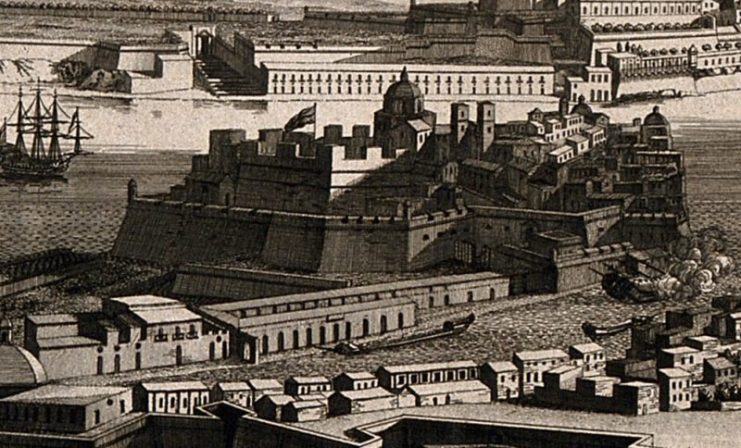

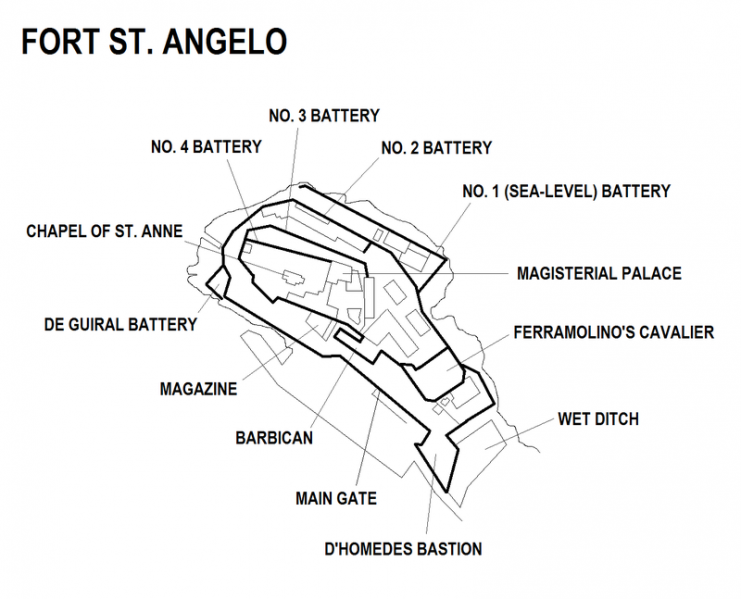

The fort of St Angelo sat on the southern side of the Grand Harbor, the most important landing point on the island. They enlarged the fort’s defenses so that it could better fend off an attack from sea or land.

They also strengthened the walls of Mdina, the old capital city of Malta. This gave them a better chance of holding this crucial strongpoint and population center.

Strozzi’s Survey

After this initial burst of activity, the defenses lay largely untouched for 20 years. Then, in 1522, Leo Strozzi, one of the order’s commanders, surveyed the defenses. He identified the points of weakness and drew them to the attention of the ruling council.

Following Strozzi’s survey, the council and the Grand Master appointed a commission to plan improvements to the defenses. Work would now begin in earnest.

portrait of the Grand Master Jean de la Vallette-Parisot (1557-1568), founder of Valletta

New Forts

One of the most impressive pieces of work undertaken by the Hospitallers was the creation of several new forts.

First came Fort St Michael, quickly constructed at the end of the Senglea peninsula. Designed by Spanish engineer Pedro Pardo, it used a star-shaped design common in the 16th century. This gave the defenders better fields of fire against anyone approaching the walls, as well as helping to deflect projectiles meant to knock holes in the defenses.

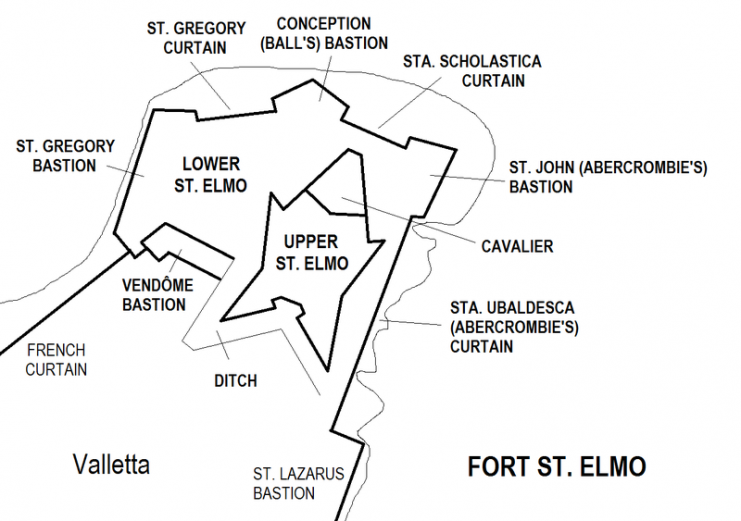

The next fort was built on more difficult terrain on the rocky Mount Sciberras headland. There had long been a watchtower at this position, but now the knights wanted something more substantial.

Another of Pardo’s forts, this one was called St Elmo. It commanded the entrance to two significant harbors – the Great Harbor and Marsamuscetto.

St Elmo was an interesting construction both for its strengths and its weaknesses. It took the shape of a four-pointed star and was built of solid stone, meaning that it could not be undermined. The sandstone and limestone walls were tall to keep out attackers, and deep ditches added extra protection on the landward side. But the haste of its construction meant that it was built of inferior quality stone. It lacked causeways and dikes to protect the defenders once a bombardment began.

Three smaller defensive positions outside the main walls of St Elmo would hold up an enemy approach while the defenders got ready. Of all the forts on the island, it was the most impressive reflection of 16th-century defensive engineering.

Rebuilding Birgu

The order had set up its main base in the small fishing village of Birgu, which was completely transformed by their presence. Arsenals, magazines, and a hospital sprang up alongside a large grain store. Tunnels dug deep into solid rock became home to galley slaves, while chapels and a new church for the Hospitallers appeared in the streets.

Defensive walls were built all around Birgu, totaling three kilometers in length. On the landward side, these included a tall rampart wall. In this wall were two bastions, protruding strongpoints that gave the defenders better fields of fire against anyone trying to storm the walls. Two smaller demibastions defended the ends of the ramparts. Outside the walls, a ditch was carved from the solid rock to block the approach.

Signal Fires and Watchtowers

It was important to spot when the enemy was coming and to spread the word when that happened. To this end, coastal watchtowers which had stood for hundreds of years were restored and brought back into working order.

These towers were equipped with warning beacons. It was a simple system to tell others about a coming attack. A pile of brushwood and faggots was kept at the tower. If an enemy was seen, this fire would be lit. Other towers would pick up the signal and light their own beacons, spreading the news across the island.

Similar warning beacons were constructed at the top of the castle at Gozo, at the city of Mdina, and atop the forts of St Angelo and St Elmo. If an attack came, the warning would spread fast.

Provisioning

By the spring of 1565, the Hospitallers knew that an attack on Malta was imminent. Members of the order came in from across Europe, ready to defend their home.

Provisions were also imported and stockpiled, to ensure that the men could endure through an extended siege. Storehouses were filled with supplies to support a growing army.

Arming Up

As the danger increased, the Hospitallers also prepared the weapons they would need to hold off the invaders. This was the early days of firearms. Gunpowder weapons, though potentially powerful, were also quite primitive.

Larger cannons were installed at the fort of St Michael. With their extra range and power, these increased the fort’s ability to defend itself and to threaten forces heading for other targets. They had enough range to reach the nearby heights of Corradino as well as to sweep the open ground that lay at the base of Mount Sciberras.

Powdermills were kept busy creating the gunpowder the defenders would need. Some of this would be used in cannons and handguns. Some went into incendiary bombs and anti-personnel fireworks, weapons designed to cause fear as well as carnage.

Meanwhile, armorers’ workshops filled with the ringing of hammers on steel as armor was refurbished and blades sharpened.

Ready for War

As the invasion approached, the commanders inspected the defenses again and prepared the men. War was coming. It would be tough, but they were ready to hold Malta and they did.