On December 2, 1943, Germany launched an air attack on the Italian town of Bari on the Adriatic coast. The town was important strategically as it was a major shipping port. It was a carefully planned surprise attack involving more than 100 aircraft of the German Luftflotte 2. The planes, which were fast moving Junkers Ju 88 bombers, hit their targets. In the raid which lasted just over an hour, they sank 27 ships, both military and civilian including transporters and cargo ships as well as a schooner.

The port was put out of action for over a year as a result of the damage. An unintended consequence of the attack was a large number of causalities suffering from mustard gas poisoning. Unfortunately, one of the wrecked ships contained a secret cargo of mustard bombs, and the poisonous gas was released into the air and sea as the ship broke up.

Little Pearl Harbor

The attack is sometimes referred to as “Little Pearl Harbor” because the allies were taken completely by surprise. They did not see the port as a likely target for attack. Not only was it inadequately protected but the harbor lights which were on through the night to help with loading and unloading ships marked the area out perfectly for the German bombers.

The Allies lost 17 ships – only one less than at Pearl Harbor. The Port of Bari had been taken without resistance by the Allies on September 11, 1943. However, despite the port’s strategic importance as a means of bringing provisions and ammunition into the country, the Allies had failed to defend it adequately from a possible air attack.

Deadly Cargo

The most famous ship lost in the raid was the SS John Harvey: a US Liberty Ship. It had arrived in Bari with a cargo of 2,000 bombs each containing 60 to 70lbs of mustard gas.

As the port was already packed with ships all waiting their turn to unload, the ship’s commander Captain Elwin F Knowes faced a dilemma. He was aware of his deadly cargo and wanted to offload it as quickly as possible. However, he could not let the port authorities know what the ship carried. Mustard gas had been prohibited by the Geneva Protocol of 1925 following its use in WW1.

He decided to wait his turn. Had he told the harbor master he would have risked being court-martialed for releasing top secret information so not surprisingly he said nothing. Although made for a good reason it was a decision which would turn out to have serious consequences.

The Air Raid

The Luftflotte made their attack on Bari Harbor, and the SS John Harvey was one of their targets. When the ship was hit, there was a massive explosion and the liquid sulfur contained in the bombs was released. It caused contamination of the sea where those who were escaping the sinking ships were trying to swim to safety.

As a result, they swallowed the poisoned water and contaminated their skin and clothes. Simple measures like washing and changing their clothing would have helped to reduce the number of injuries and fatalities. However, they did not know what they were dealing with as initially there was no visible sign of contamination.

The symptoms of mustard gas poisoning start to develop in the 24 hours following contact. The explosion also resulted in a giant cloud of toxic vapor which fell on the decks of the ships which survived the attack as well as blowing across the city.

One ship, which had survived the attack at Bari – the HMS Bicester – set off for the port at Taranto shortly afterward. By the time they arrived the mustard gas that had fallen on the deck of their ship had started to take effect. They had to request help to steer the ship into the harbor as conjunctivitis had temporarily blinded the crew as a result of their exposure.

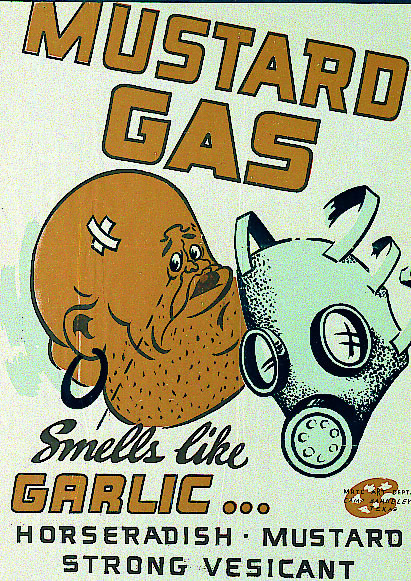

The biggest problem faced by the medical staff trying to treat the victims of the mustard gas was that no one knew the cause of their injuries. Medics were confused by the mysterious symptoms which included breathing difficulties, blisters on the skin and visual problems due to conjunctivitis and a strange garlic-like odor. They were not aware of the effects of chemical weapons and had no experience in dealing with them. Almost all the crew from the John Harvey had been lost in the raid so they could not provide the information needed to treat the patients effectively.

The Aftermath

Despite the fact that people were suffering from the effects of the gas poisoning and the local doctors did not know how to treat them, the US was initially determined to keep the presence of the bombs secret. They sent an army surgeon to the scene. Dr. Stewart F. Alexander recognized the symptoms, and the injured were able to get appropriate treatment. Dr. Alexander was later commended for his work treating the victims of the attack.

The Allies had tried to conceal the truth as they were afraid that if the Axis found out about their secret weapon, it could escalate the risk of serious chemical warfare. The Allies eventually admitted they had developed the mustard bomb to be used in defense, not as the first line of attack.

Despite this admission, deaths resulting from the Allies mustard bombs at Bari were registered as “burns due to enemy action.”

Perhaps the only positive thing to come from the incident was that samples of tissue from autopsies were preserved for research purposes. These were used to help develop the drug based on sulfur mustard which would become one of the first chemotherapy drugs used in the treatment of cancer.