Few things are more important in war than knowing what is going on. Good intelligence, such as that gathered by the British after cracking the Enigma code, can give one side a huge advantage. Poor intelligence gathering and the failure to reconnoiter the territory can be equally decisive in ruining a campaign.

1. Lake Trasimene

Incompetence isn’t a word we normally associate with the armies of republican Rome, armies led by such greats as Marius, Pompey and Caesar. But like any nation, they had their share of failures at the top. The Carthaginian general Hannibal’s success against the Romans was largely down to his own skill, but Romans also played their part.

When an army led by Consul Flaminius pursued Hannibal through Italy in 217 BC, Flaminius was in such a rush to catch the invaders that he failed to set up proper reconnaissance. Marching blindly into the valley of Lake Trasimene, he was ambushed by Carthaginian forces hidden on the valley side. Flaminius’s army was smashed, and Hannibal continued roaming the Roman Empire unchecked.

2. Harald Hardrada Invades England

Even capable commanders have bad days. When these occur during wartime they can be disastrous.

The Norwegian King Harald Hardrada was an experienced war leader, having served in the Byzantine Varangian Guard and proved his worth leading Viking forces. Invading northern England in 1066, he defeated the local militia at Fulford and settled in to wait for the English King Harold Godwinson to come to him.

Hardrada was confident that it would take Godwinson many days to bring his army from the south coast up to Yorkshire, and so he let his army relax along the banks of the River Derwent and strip off their armour in the summer heat. No Norwegian scouts spotted the English army on its forced march north, and so Godwinson took Hardrada by surprise. The Norwegians on the west bank of the river were overrun and, despite one man’s heroic defence of the bridge, the English fought their way across to defeat the remaining Vikings in a bloody battle.

3. General Harmar Harasses the Indians

From the early years of the United States of American, a certain type of military commander relished raiding into native territory. One of these men was General Harmar, who in June 1790 led a force of 1,500 men – most of them irregulars – on just such a raid.

Focused on plunder rather than discipline, Harmar abandoned sensible precautions, believing that the locals were no threat. He split his troops into small groups referred to as “penny packets” and did little to establish the location of native troops.

As a result, two of Harmar’s detachments were wiped out in ambushes. The general hurriedly gathered his remaining forces and retreated to safety.

4. General St. Clair: Harmar Mark Two

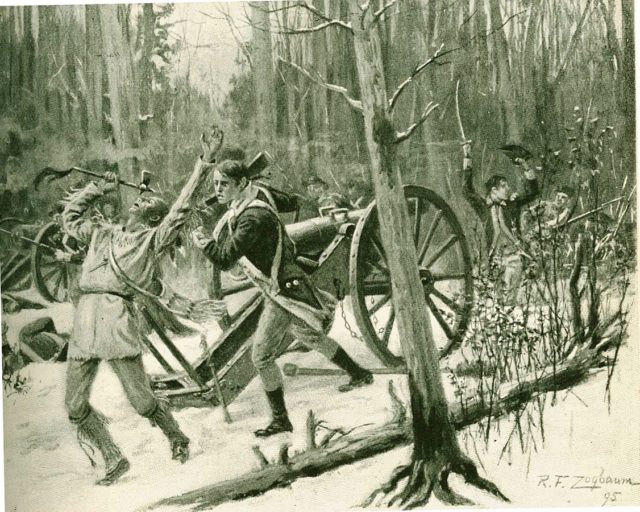

Those who do not learn from history are doomed to repeat it. Unfortunately, those who learn the wrong lesson are also doomed to disaster. And so it was that a year after Harmar’s retreat, General St. Clair set off on another disastrous raid into native American territory.

St. Clair knew what had happened to Harmar, and thought he knew why the other general had failed – his “penny packets”. Instead of dividing his 2,000 men, St. Clair kept them in a single column. He was so obsessed with not dividing his troops that he did not send out scouts, instead marching forward without reconnaissance.

With no scouts out, St. Clair was completely unaware of the force of 1,000 natives approaching his army. On 3 November 1791, these native surrounded the invaders’ camp, creeping up on it unseen. Just before dawn they launched their attack, killing 637 men and forcing yet another force from the United States into a humiliating retreat.

5. Shenck and the “Masked Batteries”

Another way to avoid learning from mistakes is denial.

During the American Civil War, Union General Robert C. Shenck led a patrol through Virginia without any advance guards or scouts providing reconnaissance. In an all too familiar pattern, the force without scouts walked into an ambush and was defeated by Confederate infantry supported by two cannons.

Rather than admit that his incompetence had let him be so easily defeated, Shenck claimed that he had been attacked by hidden batteries of artillery. This lie – or possibly self-delusion – turned into a myth that spread through the Union army, causing fear and undue caution.

6. The Franco-Prussian War

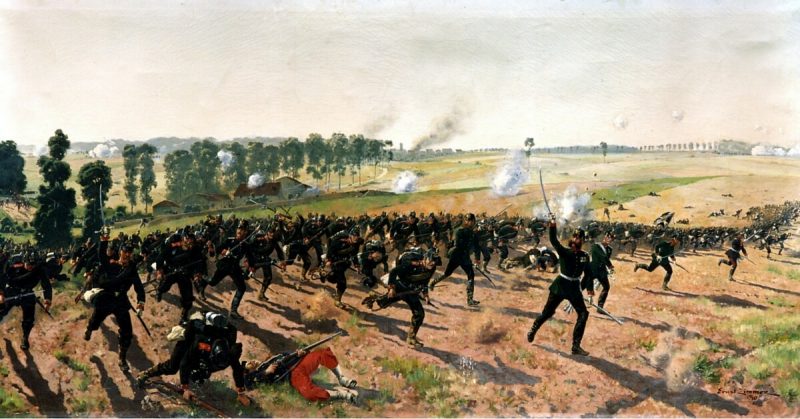

The Franco-Prussian war of 1870-71 is mostly remembered as an example of one professional, competent army defeating a worse run one, leading to victory for the Prussians and their allies. But this isn’t to say that the Prussian approach was flawless.

Both sides repeatedly failed to properly reconnoitre each other, leading to unexpected battles, in which troops unwittingly bumped into each other as they crossed the landscape. Regiments found themselves caught in combat without proper instructions, as they unexpectedly encountered their equally unready opponents.

7. The Battle of Adowa

The Italian desire for African colonies like those of other European powers led them to invade Ethiopia in the late 19th century. Here more than anywhere, Europeans proved their ability to underestimate the locals in the Scramble for Africa. The Ethiopians knew their terrain, could muster substantial armies, and bought modern armaments off the Russians and French.

General Baratieri, leading the Italian troops in 1896, made this fatal error of underestimation at the Battle of Adowa. But he was also brought down by his reconnaissance. His maps were faulty; spies incorrectly informed him that half the enemy forces were away gathering food, and he failed to correctly identify the location of the numerically superior Ethiopian army.

As a result, Baratieri divided his force into four separate columns meant to converge on the enemy. Heading for the wrong place, they were spotted by the Ethiopians and each Italian column was defeated separately.

These battles all underline the critical role of scouting and reconnaissance in battle, which is still important to this day.