War History Online presents this Guest Article from Martin K.A. Morgan

On June 8, 2001 representatives of British Petroleum (BP), Shell Oil Company and the Minerals Management Service (MMS) of the US Department of the Interior held a press conference to announce the discovery of a significant and historic maritime wreck site: the discovery of the German submarine U- 166. C & C Technologies, Inc. of Lafayette, Louisiana located the wreck during the month of March 2001 while surveying a planned deepwater pipeline route for BP and Shell.

The tool used to conduct the survey was a state of the art remotely controlled submarine, or Autonomous Underwater Vehicle (AUV), operated by C & C. Sensors on board the 18-foot long AUV, named Hugin-3000, were used to acquire acoustic imagery of the ocean floor as well as to determine precise water depths. At a depth of almost 5,000 feet, in a position approximately 45 miles southeast of the mouth of the Mississippi River, Hugin-3000 detected obviously man-made wreckage.

To Robert Church and Dan Warren of C & C Technologies, the sonar-generated acoustic image of the wreckage appeared suspiciously like a U- Boat. Suspecting that the wreckage of a submarine had been discovered, C & C Technologies, BP and Shell brought the discovery to the attention of the Minerals Management Service. At the time, the MMS was the federal agency that managed the nation’s natural gas and oil resources on the outer continental shelf – the area where the wreckage was discovered. In addition to mineral resources management, MMS was responsible for protecting underwater cultural resources like historic shipwrecks.

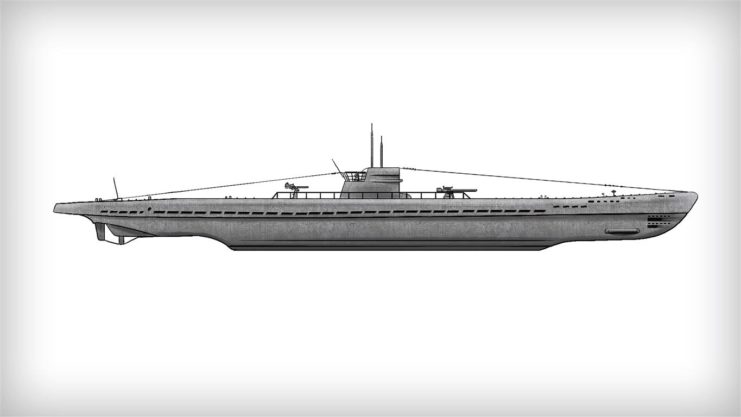

After analyzing the acoustic imagery, BP, Shell, C & C and the MMS reached a decision that further investigation of the sunken vessel was necessary to establish its identity. To accomplish this task, the research vessel R/V Gary Chouest was dispatched to the scene. Through the use of a tethered Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV), Gary Chouest was able to capture video footage of the sunken submarine. That footage revealed the unmistakable lines of a Type IXC U-Boat. Easily identifiable in the ROV video were such objects as the vessel’s conning tower and ‘Wintergarten’ (the railed-in area of the conning tower just aft of command bridge), the forward 105mm gun and the vessel’s anti-aircraft armament – a single 20mm gun in the ‘Wintergarten’ and a single 37mm gun on the aft deck. The ROV footage also revealed evidence of a violent death.

Although the U-Boat’s hull remains largely intact, the bow section of the vessel lies separated from the rest by several hundred feet. The ROV footage captured images of catastrophic damage to the severed bow. In addition to the fact that this portion of the boat is no longer attached to the hull, it appears that an incredible force crushed the deck area – apparently the work of a well-placed depth charge.

Although the battle-damaged wreckage revealed evidence of the fate of U-166, the location of the wreck-site generated the most surprising revelations about the submarine’s fate. Disproving the traditionally accepted theory of the submarine’s destruction, C & C Technologies, BP and Shell discovered the sunken U-Boat 130 miles east of where the US Coast Guard and the US Navy thought it would be. The wreckage of U-166, in an upright and even-keeled position, lies southeast of the mouth of the Mississippi River in a particularly deep area of the Gulf of Mexico known as the Mississippi Canyon.

Since the 1940s, the final resting place of U-166 was thought to be in 10 fathoms just to the south of Isles Dernieres, Louisiana, not in 800 fathoms at the bottom of the Mississippi Canyon. Since the 1940s, U-166 was thought to have sunk as a result of damage sustained during an air attack. The location of the wreckage proved that not to be the case – necessitating a rewrite of this chapter of World War II history.

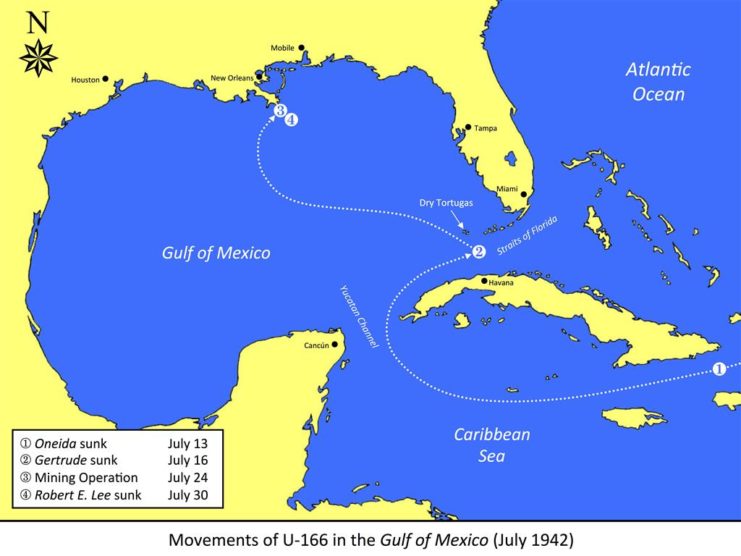

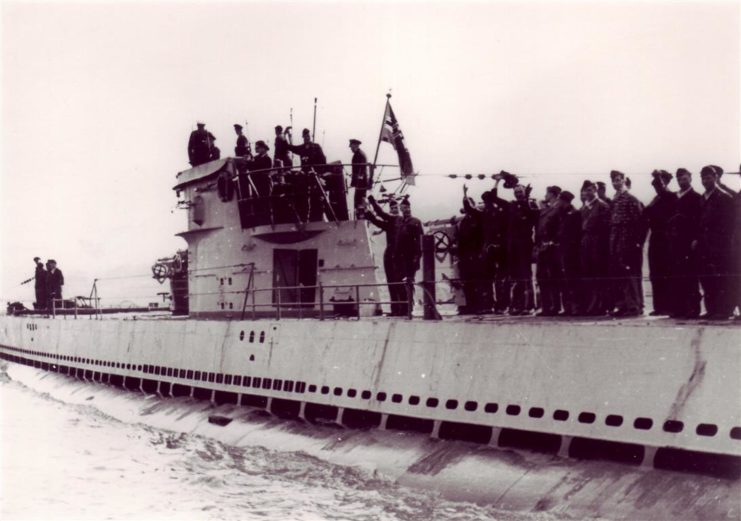

The keel of U-166 was laid down on December 6, 1940 at the Seebeck Shipyard in Bremen, Germany. After completion of construction, U-166 was commissioned on March 23, 1942 with 29-year-old Oberleutnant zur See Hans-Günther Kühlmann, Commanding. U-166 made two voyages during its career. The first, a training cruise, began on March 23, 1942 and ended on 31 May 1942. Following this ‘shake down’ cruise, U-166 was assigned to a combat unit – the Kriegsmarine 10. Unterseebootsflottille (10th Submarine Flotilla). On June 17, 1942 U-166 departed occupied France on its first and only war cruise.

After clearing port, U-166 headed west toward the Gulf of Mexico to conduct mining operations and merchant warfare against Allied shipping there. Kühlmann and his crew, like others before and after, were destined to be a part of an operation code-named Paukenschlag (which translates as “roll of the drums” or “drumbeat”). Soon after declaring war against the United States on December 11, 1941, Germany launched a submarine offensive against American coastal waters. Through interdiction, this campaign was designed to cripple Allied ability to supply sustained operations overseas. At first Operation Drumbeat targeted the Atlantic coast, but the action ultimately spread to the warm waters of the Gulf of Mexico.

In early May 1942, Korvettenkapitän Harro Schacht’s U-507 became the first U-Boat to enter the Gulf of Mexico during World War II. Before the end of the month, five other U-Boats discovered targets in the Gulf of Mexico to be plentiful and vulnerable. Due to an almost unbelievable alignment of circumstances, the U-Boats enjoyed significant advantages over the ships they hunted. During the early weeks of the battle in the Gulf, German submariners did not face coastal blackouts – instead, they faced quite the opposite. In fact, Korvettenkapitän Schacht made an entry in his ship’s log relating to what he saw of the American coast from the tower of U-507 as it entered the Gulf.

“At the Florida Straits. I’m going to get to my area of operations via Tortugas Bank [just off Key West]. The Tortugas navigational lights burn as though it were peacetime.”

Giving them a further operational advantage, the Germans did not confront escorted convoys either. At a time when coastal lights burned bright, U-Boats found scores of merchant ships sailing alone and defenseless in the waters of the Gulf. Enhancing the force and effect of the German onslaught, many of these targets carried crucially important war commodities – primarily petroleum products from the vast oil fields and refineries of Texas and Louisiana. There was also an appalling scarcity of aircraft available for anti-submarine patrol. Jakob May, who served as a radio operator aboard one of the U- Boats that hunted merchant ships in the Gulf that summer, described the air patrols his U-Boat encountered:

“It wasn’t too dangerous because the Americans were not yet terribly experienced in aerial operations. Several times aircraft overflew us when we were on the surface recharging, but nothing happened. It was evident for us that the Americans did not yet have matters in hand in the Gulf of Mexico.”

With such a strong tactical advantage, the Germans quickly accumulated a dramatic record of success. In fact, during the month of May 1942, more ships were sunk in the area known as the Gulf Sea Frontier (GSF) than anywhere else on earth. Before the end of that month, 41 Allied vessels had been sent to the bottom in the GSF by German submarines.

The damage was more than just physical. The psychological result of this early rash of sinkings was the introduction of a measure of anxiety into the lives of Americans from Florida to Texas. Fed by mariners and coastal residents alike, rumors began circulating about the U-Boats prowling waters that had never before been thought of as a war zone. Although often exaggerated, the spreading public awareness of U-Boat operations was firmly rooted in basic truths about the destructive war being waged in the Gulf. Even to Robert Budlong, living in the remote islands fringing the northern Florida Straits, the presence of German submarines was evidently well known. At Garden Key in the Dry Tortugas, the National Park Service maintained the Fort Jefferson National Monument a distant 68 miles west of Key West, Florida.

Designed to protect the natural deep-water anchorage in the center of the Tortugas, construction of Fort Jefferson began in 1846 and continued into the 1870’s. The product of a massive and expensive engineering project, Fort Jefferson is a masonry fortification of enormous proportions and imposing appearance. Although of great strategic importance during the 19th Century, Fort Jefferson’s military usefulness had waned by the turn of the 20th Century. In 1935, President Roosevelt turned the property over to the Department of the Interior and designated the old fort a National Monument. In his capacity as superintendent of the Fort Jefferson National Monument, Robert Budlong prepared and submitted a narrative report to the Director of the National Park Service each month. In his report for the month of May 1942, Budlong made a telling statement of the anxiety that had become common:

“A total of 121 persons visited the Monument during the month of May. They arrived in 14 boats and 2 airplanes. This month, however, no private yachts came to the Monument; the Gulf has an evil reputation these days.”

Considering that the 41 ships sunk in the Gulf that May represents the highest loss of allied shipping for any single month during the entire war, that evil reputation certainly seems well deserved.

Caught off guard by the initial surprise of Paukenschlag, the Americans were in full recovery by the time U-166 arrived on the scene in July 1942. Although the U-Boats had devastated allied shipping in the Gulf in May and June, with the arrival of July the worthwhile targets were becoming more and more scarce. Joining the slow and vulnerable solitary freighters and tankers, armed US aircraft and surface vessels began conducting organized anti-submarine warfare patrols. This inhospitable environment was the destination of U-166 when it departed occupied France on June 17th.

Crossing the Atlantic did not happen without incident, though. During the middle of the night of June 20th, U-166 was illuminated by an airplane searchlight and attacked with aerial bombs. The bombing did no damage and the U-Boat continued on its journey toward the Gulf of Mexico. In compliance with orders, Oberleutnant Kühlmann reported his fuel level upon passing 50 West on July 3rd. After successfully crossing the Atlantic, U-166 began combat operations in the Caribbean Sea as it approached its patrol area.

The submarine spotted a convoy consisting of two steamers and two destroyers on July 10th and attacked firing six torpedoes – all of which were misfires. On July 11, 1942, the submarine scored its first victory when it sank the 84-ton sailing vessel Carmen near the Dominican Republic. On July 13th, U-166 briefly pursued a convoy and, late in the day, attacked and sank the 2,309- ton American merchant freighter Oneida in the Windward Passage close to the extreme eastern tip of Cuba. On the following day, U-166 entered the Gulf of Mexico through the Yucatan Channel. Oberleutnant Kühlmann then steered the U-Boat to the vicinity of the Florida Straits – an area that only ten weeks earlier had been full of targets. At 4:00 a.m. on July 16, 1942, U-166 intercepted the 16-ton trawler MS Gertrude south of the Dry Tortugas.

Gertrude was en route between Miami and Havana with 40,000 pounds of onions. Oberleutnant Kühlmann allowed the crew of the Gertrude to abandon ship and then he ordered the crew of U-166’s 105mm deck gun to sink the vessel. The U.S. Coast Guard rescued the three survivors on July 19th. Kühlmann was not finding the same large, valuable and unarmed targets that his predecessors had found near the Tortugas just two and a half months prior. At that point, Kühlmann steered U-166 toward its patrol area – operational area DA-90, the grid sector that covered the mouth of the Mississippi River on Kriegsmarine nautical charts. After entering area DA-90, U-166 laid nine anti-ship submarine mines 600 meters off of the jetties of the Southwest Pass of the Mississippi River during the night of July 24th/25th.

Although the presence of such mines may seem a menacing threat, they never did any damage to Allied shipping. After completing the mining operation, the vessel steered back out into the open waters of the Gulf to continue hunting. On July 27th, the submarine transmitted a message to Kriegsmarine headquarters announcing the completion of the mining mission. That message was the last transmission that U-166 would ever send.

Enter SS Robert E. Lee

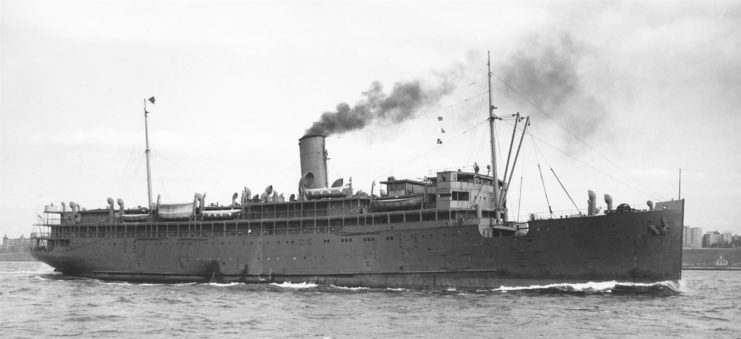

On July 30, 1942, U-166 crossed paths with the SS Robert E. Lee East-South-East of the Southwest Pass of the Mississippi River. The 5,184-ton commercial passenger/freighter had departed Trinidad the previous week carrying 131 crewmembers, 6 U.S. Navy Armed Guards and 270 passengers – some of which were survivors of other ships sunk by German submarines earlier that summer. Robert E. Lee entered the Gulf of Mexico through the Yucatan Channel and then proceeded to Key West, arriving there on 29 July. From Key West, Robert E. Lee sailed to Egmont Key at the entrance to Tampa Bay with the intention of entering the bay. However, no harbor pilot was available to guide the vessel into the inner harbor that night, so the Robert E. Lee proceeded on toward New Orleans.

When the Robert E. Lee was 45 miles southeast of the mouth of the Mississippi River the following afternoon, a single torpedo struck the ship’s starboard side aft of the engine room, causing the ship to sink within 15 minutes. Of the 407 people on board the ship, 10 crewmembers and 15 passengers perished. However, Robert E. Lee was not steaming alone. She was in convoy with a naval escort that swiftly responded to the attack. Within minutes PC-566, a US Navy patrol craft, charged after a periscope that had been sighted. PC-566 acquired sonar contact with the submarine, passed over the contact and released a pattern of five depth charges.

After the detonation of the first five depth charges, PC-566 doubled back, acquired sonar contact with the diving target again and released five more depth charges. With almost fictional poetic justice, PC-566 became an avenging angel when one, if not more than one, of those ten depth charges caused fatal damage to U-166. The joint BP/Shell/MMS confirmation expedition in 2001 proved that the bow of U-166 was blown off during PC-566’s depth charge attack. This damage resulted in the loss of the submarine and all 52 members of its crew.

The wreckage of U-166 lies on the bottom within one mile of the wreckage of its last victim – the SS Robert E. Lee. The close proximity of the two wrecks has proven that both vessels met their end on that fateful July afternoon. The close proximity of the two wrecks makes it obvious that, for more than 70 years now, historians have been passing on an incorrect explanation of the demise of U-166. Since World War II, the accepted belief had been that U-166 survived PC-566’s depth charge attack. According to the old, inaccurate, account of the last days of U-166, the submarine limped away from the scene of the crime following the sinking of Robert E. Lee and sailed to the west.

Enter V-212

The now abandoned theory of the loss of U-166 held that the U-Boat was 130 miles to the west two days after the Robert E. Lee sinking. This old hypothesis suggested that U-166 was on the surface of the Gulf just to the south of Isles Dernieres, Louisiana on the afternoon of August 1, 1942, when a U.S. Coast Guard patrol plane spotted, attacked and sank the sub. The Coast Guard plane, a Grumman J4F-1 Widgeon seaplane (bearing the hull number V-212) based in Houma, Louisiana, was thought to have fatally damaged U-166 with a single 325-pound depth charge. V-212 is now in the collection of the National Museum of Naval Aviation in Pensacola, Florida, where it is displayed with a sign crediting it for sinking U-166. While it is now obvious that this J4F-1 Widgeon did not sink U-166, a fascinating new theory has emerged to explain what V-212 did do.

On that date, Chief Aviation Pilot Henry White and Radioman 1st Class George Boggs, Jr. were on routine anti-submarine patrol when they spotted a surfaced submarine and attacked it. As the Widgeon made its approach, the submarine began a crash dive to evade the attack. When Boggs released the depth charge, the U-Boat was already completely submerged but still visible beneath the water. Boggs observed the depth charge enter the water close to the vessel and then detonate. Within a few minutes, White and Boggs observed an oil slick on the surface and reported that the submarine had been damaged. Later, the Coast Guard credited the two men with sinking Kühlmann’s boat. Based on the reports of these two men, it is obvious that they did indeed attack a German U- Boat, but as the evidence now shows, that boat was not U-166.

A mystery solved

Despite more than 70 years of reporting to the contrary, it is now obvious that the Coast Guard J4F-1 Widgeon (V-212) flown by White and Boggs attacked U-171 on August 1, 1942. The discovery of U-166 wreckage provides undeniable evidence that PC-566 had already destroyed it two days earlier, 130 miles away. However, in addition to the location of the wreckage of U-166, there is other compelling evidence that supports the conclusion that V-212 attacked U-171. To begin with, U-171 was the only other U-Boat in operational area DA-90 on August 1, 1942. U-171 and U-166 were both Type IXC U-Boats and were consequently nearly identical in appearance – making the confusion understandable. Also, it is a matter of empirical fact that U-171 was hunting in the waters south of Isles Dernieres during the period in question. This is known with absolute certainty because U-171 sank SS R.M. Parker, Jr. at 28°37’N 90°48’W just 12 days after V-212’s aerial attack on August 1, 1942 at 28°37’N 90°45’W.

Knowing that U-166 was on the bottom of the Gulf of Mexico on August 1, 1942 when V-212 attacked a surfaced submarine, and knowing that U-171 sank SS R.M. Parker, Jr. at a position only 2.66 nautical miles away just 12 days later, it is entirely reasonable to conclude that U-171 was the target of V-212’s aerial attack. The fact that the aerial attack and the sinking of the R.M. Parker, Jr. took place in such close proximity to one another puts U-171 at the right place at the right time to support the theory and thus has to be recognized as being much more than mere coincidence.

Perhaps the most convincing evidence in support of this theory though is the testimony of U- 171’s commanding officer – Oberleutnant zur See Günther Pfeffer. U-171 sank in the Bay of Biscay on October 9, 1942 after hitting an anti-ship mine. When U-171 sank, the logbooks detailing daily operations went down with the ship. Without that crucially important piece of evidence, reconstructing the U-Boat’s combat patrol in the Gulf of Mexico is an imprecise endeavor. As challenging as that may seem though, a helpful but imperfect piece of evidence exists. After the loss of his ship, Oberleutnant Pfeffer was required to testify before an investigative court of inquiry relating to the disaster.

During those hearings, Oberleutnant Pfeffer entered a statement describing the loss of his ship. The transcript of Pfeffer’s statement also includes a reconstruction of U-171’s daily operations while hunting in the Gulf of Mexico. In this reconstructed log, Oberleutnant Pfeffer described being the target of an aerial attack off the coast of Louisiana. He even revealed the attacker to be a seaplane that dropped a single depth charge.

U-166 and U-171 were the last two German submarines to operate in the Gulf of Mexico during the great U-Boat offensive of the summer of 1942. The Germans sent more U-Boats into the Gulf during 1943, but in much fewer numbers and with far more modest results. Between March and December of that year, only four Allied ships were sunk. The renewed campaign of 1943 did not involve the deep penetrations into the Gulf that were such a part of the campaign of 1942. None of the U-Boats to operate in Gulf waters in 1943 hunted in operational area DA-90 – Pfeffer’s U-171 holds the distinction of being the last German U-Boat to do that during WWII. Because of this significant discovery, the dramatic events of July 30, 1942 are finally understood. Almost 75 years after the fact, this particular episode of World War II history has been re-written and the final resting place of 52 Kriegsmarine sailors has been noted. All the while, the two victims of that fateful day, the SS Robert E. Lee and the U-166, continue to rest on the bottom as they have for more than seven decades – both as war graves.

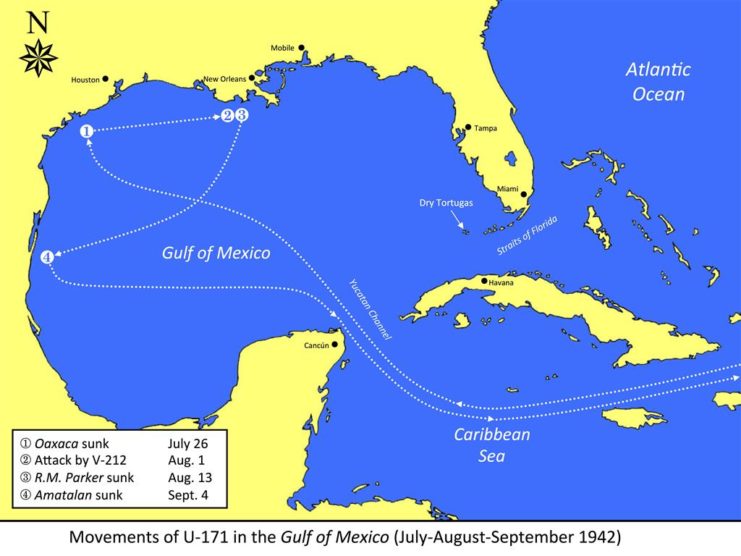

Enter U-171

The keel of U-171 was laid down on December 1, 1940 at the AG Weser Shipyard in Bremen, Germany. After completion of construction, U-171 was commissioned on October 25, 1941 with Oberleutnant zur See Günther Pfeffer, Commanding. Like U-166, U-171 made only two voyages during its brief career: a training cruise and a single combat patrol. Following the training cruise, U-171 was assigned to the same combat unit as U-166 – the Kriegsmarine 10. Unterseebootsflottille. On July 1, 1942, U-171 departed occupied France bound for the Gulf of Mexico to conduct merchant warfare against Allied shipping there. Like U-166, it would be the submarine’s first and only war cruise.

On July 7, 1942, U-171 met U-460 at a predetermined rendezvous point in the middle of the Atlantic. U-460, a Type XIV U-tanker or “Milchkuh” (“Milk Cow”), transferred sufficient fuel and provisions to U-171 to allow the vessel to operate for an extended period of 125 days. Because of this re-supply rendezvous, U-171 remained on its combat patrol longer than any other U-Boat to operate in the Gulf of Mexico. After entering the Gulf through the Yucatan Channel, U-171 proceeded to the waters just off the coast of Texas between Corpus Christi and Galveston. It was there that, just before dawn on July 26, 1942, the submarine sank the Mexican ship Oaxaca. Ironically, the Oaxaca was a former German ship known as the Hamlen. At that point, U-171 sailed east away from the Texas coast, toward operational area DA-90. Thus, during the last week in July and the first week in August, U-171 was moving through the waters just south of Isles Dernieres, Louisiana.

On August 13, 1942, U-171 attacked and sank the 6,779-ton Tanker SS R.M. Parker, Jr. Oberleutnant Pfeffer fired two torpedoes into the 425-foot long ship and then surfaced and shelled the sinking vessel with U-171’s 105mm deck gun. Following that sinking, Oberleutnant Pfeffer experienced no further luck finding unprotected ships in American waters, so he moved U-171 back to the southwest toward the Mexican coast. It was there on September 4, 1942 that the U-Boat intercepted and sank the tanker Amatalan north of Tampico. The sinking of the Amatalan was the last to occur in the Gulf of Mexico during the great U-Boat offensive of the spring and summer of 1942.

After sinking Amatalan, Oberleutnant Pfeffer and his crew began their return voyage across the Atlantic. Although U-171 survived combat operations in the Gulf of Mexico and the dangerous return voyage across the Atlantic, the U-Boat was fated to meet its end within sight of its homeport. On October 9, 1942, U-171 struck a mine while entering port at Lorient in occupied France. As a result of the explosion and the sinking that followed, 22 of Oberleutnant Pfeffer’s crew of 52 perished. Pfeffer himself survived the accident. It remains a significant irony that U-171 survived the many hazards and perils of its extended combat patrol, only to be destroyed within sight of its home base.