War History Online presents this Guest Article from Richard F. Johnston

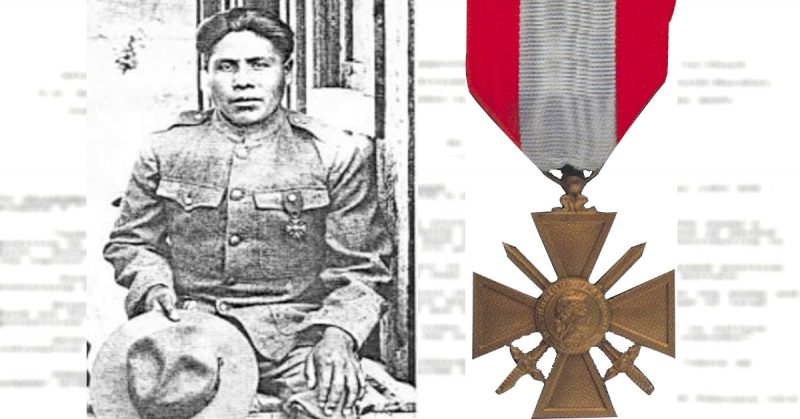

When World War I broke out, Choctaw Indian Joseph Oklahombi from Wright City, Oklahoma, felt it was time to “Do his duty”. With a name which translates to “Man Killer”, he knew he must uphold his name and follow in the footsteps of his ancestors. After completing basic training as a 26-year-old army private, he along with his fellow Choctaws were shipped overseas as part of Company D, 141st Infantry, 26th division.

Arriving in Champagne, France in September 1918, a frontal assault is scheduled to begin on October 8th at 5:30 am near the village of Saint-Etienne-à-Arnes. Lacking grenades, he carves one out of a potato and waits impatiently with his patrol composed of 23 men. With his adrenaline pumping and tiring of the wait, Joseph charges “over the top” earlier than the others and lets out a blood curdling war cry.

Making his way through the barb wire, crossfire from 50 machine guns and exploding shells, he attacks a German machine gun nest and shoots several soldiers before taking over the position. Later, his patrol catches up to Joseph but they’re all pinned down by German counter attacks for four days without food and water.

When re-enforcements finally arrive, the patrol has accumulated 171 prisoners and their weapons(machines guns and trench mortars) Lt. Ford, recommended each soldier be awarded the Distinguished Service Cross but so many had been previously been awarded that the citation was lowered to that of a Silver Star.

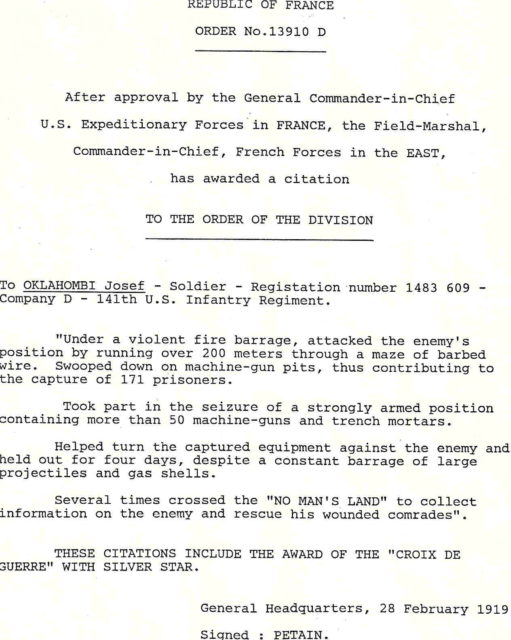

Here is Joseph’s French citation translated into English:

“Under a violent barrage he dashed to the attack of the enemy position covering 200 yards through barbed wire entanglements. He rushed on machine gun nests, contributing to the capture of 171 prisoners. Took part in storming a strongly held position containing a number of trench mortars and helped turn the captured guns on the enemy and held said position for four days, in spite of a constant barrage of large projectiles and gas shells. He crossed No Man’s land many times to get information on the enemy and rescue his wounded comrades.”

For this bravery, he was presented the French Croix De Guerre medal with Silver Star (given at the division level). As the war was grinding to a bloody end, Joseph’s unit had suffered 75% casualties and the current offensive had stalled. Apparently, the Germans were tapping the communications lines and intercepting most all radio transmissions. Thus, they knew what the Americans were about to do and blocked their every move.

An American officer noticed a group of Choctaws (including Oklahombi) talking in their native tongue and got an idea for thwarting the Germans by allowing the Choctaws to control all the communications. This worked brilliantly as the enemy had no idea what they were saying and the last major offensive by the Americans was successful, resulting in a shortening of the war and saving lives.

Due to the prejudices of the times, no minority soldier was ever recommended for a Medal of Honor. In addition, American Indians weren’t given U.S. citizenship until 1924.

It wasn’t until later, that the Dept. of the Army in 1992 was asked to review Black American records and as a result, upgraded two black soldiers’ medals from a distinguished service cross to the highest medal.

Many have attempted and are still attempting to get Oklahombi’s Silver Star upgraded to a Medal of Honor but because prejudice against minorities was very evident at the time and witnesses of his other acts of valor weren’t documented by his fellow soldiers, upgrades to date have been futile. Asked by Oklahombi what he thought of Army he quipped “Too much salute, not enough shoot!” Contributor – Nellie Garrone.

Richard F. Johnston

Photos provided by the author.