We also served!

The words on a monument to the code breakers of World War II to be found at Bletchley Park in Buckinghamshire in the UK.

This once top-secret base or Station X was where at one stage towards the end of the war 10,000 people worked and some how it remained a secret after the conflict even up to the days of the Cold War. The words on the memorial record the fact that although the staff was civilian with military specialists perhaps some would have thought they should be at the front with thousands of others fighting their way across Europe or the Far East. However the work they were doing probably shortened the war by 2 years and saved maybe hundreds of thousands of lives too!

Apart from the main house in the grounds of Bletchley Park and the surrounding buildings are very humble and it is those more basic buildings that the museum wants to save and is saving currently. Only recently over £8m had been spent on refurbishing a set of wooden huts used by the secret code breakers and stripped back to there wartime look. Also what is now the main entrance, shop and café area and the first part of the museum too has even had paint analysis done so they could repaint the exterior and interiors as it was when this extension building was hastily built to house machinery needed for processing vast amounts of data.

The rural retreat for the boffins based there was certainly no picnic in the country. The feeling of the working environment of the linguists and mathematicians that worked there has been captured really well in the 70 year old buildings many a little better than a wooden garden sheds of today.

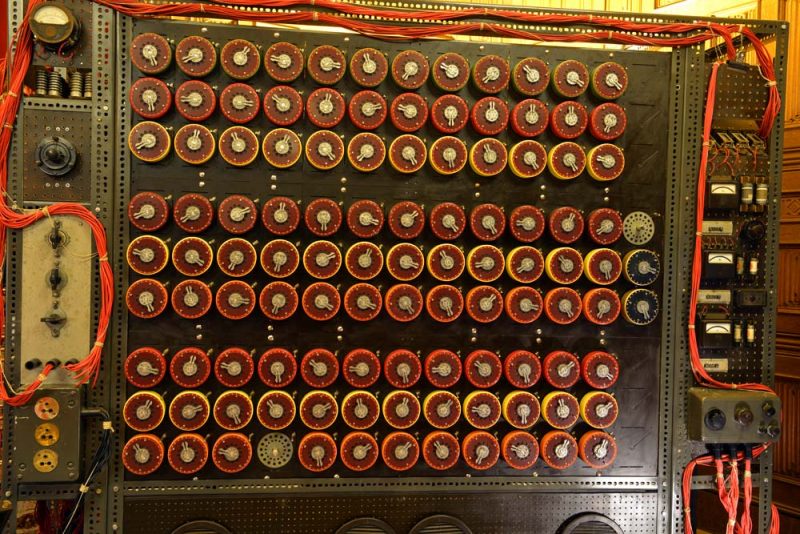

Many of the staff worked under a huge deal of pressure, from the mainly young female radio operators that recorded rapid Morse signals from the German military and at the same time trying to carefully note down every letter in the coded message series, as to miss a letter could turn out to be vital in helping to crack its code for that day. However that was just one part of the operation, those messages needed to be decoded and in the early days simple sheets of letters were used to crack some messages but it was slow painstaking work and so a new method was needed and in the end a machine or rather a very early computer was required to turn around the cyphers much quicker. Hence coming on the scene the brilliant mathematician Alan Turing who was working on Naval signals from the Germans and he and along with a close team helped to design an ‘engine’ to massively speed up the whole process and the Bombe was born, in doing so allowed the allies to know what the Nazis were doing but even more important very quickly so they had time to act.

A team of Polish mathematicians had done some of the initial code cracking of early Enigma machines but Turing and his team moved it to the next level as the Germans increased security on them by increasing the number of coding rotors.

Then the Lorenz cipher machine came into use by the German High command and that required a huge increase in what was needed to calculate machine codes. That was really when the first real computer was constructed called ‘Colossus’ designed by Tommy Flowers. Several were built but later all were destroyed to further maintain the secrecy around the whole code cracking project.

Secrecy about the base was paramount and even commanders in the field from the Navy, Airforce and Army never knew where the information they were asked to act on, came from. This also applied to the Nazis to some extent, as this is where the allies set up many deception plans in order to just let them think that for instance a bombing raid was intercepted by pure chance as a patrol was in the area. Whereas it was sent there with an advanced location warning that had been intercepted earlier.

They even set up fake agent reports coming in from Germany to further wrong foot the Nazi commanders. The largest deception plan of all was the faint to pretend to be attacking and invading the Calais area just before ‘D’ Day when in fact it was hundreds of miles away in Normandy. Cracking what was the Enigma machine codes was the main focus of the station however the museum now is very much focused on what it was like for the actual people who worked there and the complex now has gone to great deal of trouble to give visitors an experience of what it was like to be involved with this vital work.

Small dingy single offices made up a huge amount of the many wooden huts that were built as the code breaking work developed and more and more staff was needed. The huts although they had many people working in them no one knew what the person next door was doing, although they were only a slim partition of a wall away.

Again keeping all their individual secrets, secret!

Workers at the centre were not supposed to talk about their work in anyway to their fellow workers or family and they all had to sign the official secrets act. Many who had been there never spoke about any of their work and took those secrets to their graves. Now much of the their work is in the public domain and there on display for all to see, along with the largest collection of Enigma machines in the world and mock ups of the Bombe machine showing how they looked and what they sounded like in operation. The extensive grounds around the main house make up the museum so it is a good idea to wear outdoor clothes as the site is reasonably large and here even now the grounds have been restored to how they would have looked in 1939.

As the first director of the site Commander Alastair Denniston was operational head of GC&CS (Government Code and Cypher School) from 1919 to 1942 and realised and he knew that the mental strain and concentration needed by them was intense so he wanted them to have the chance to relax and unwind in the more calming landscape when they took their breaks, to think! He himself had great views over the gardens from his ground floor office in the main house, which has been perfectly recreated and is open for visitors.

In the grounds now as you walk around you will hear an audio soundscape of recordings like staff playing games, or tennis a spitfire flying over and even a motor bike dispatch rider arriving. There is an excellent memorial statue to Alan Turing in the first part of the complex and its very detailed use of tiny fragments of slate stunningly created by artist Stephen Kettle that speaks perfectly of the story of the man and his work there. Getting to Bletchley is so easy. Trains direct from London can reach it in around 50 minutes from Euston station. The museum is just a 5 minute and I mean 5 minute walk from the station it could not be easier. If you arrive by car there are plenty of signs in and around the town to point the way and there is plenty of parking on site.

This very popular museum is building visitor numbers with its refurbishment work and numerous exhibitions planned for the coming year. Since last year’s its visitor numbers have increased by around 25%. Certainly there is plenty to occupy visitors of all ages, interactive games for the youngsters as they go around and with the exhibition awash with items from that war period many older or former military visitors will have plenty to be nostalgic about.

Geoff

www.thetraveltrunk.net Facebook Twitter