War History online proudly presents this Guest Piece from Jeremy P. Ämick, who is a military historian and writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.

For many years, David Russell of Lohman, Mo., has stored a worn military trunk once belonging to his late father, Peyton Russell. Recently, he and some friends were able to pick the lock on the trunk that contained items accrued during his father’s lengthy military career, including diaries that chronicled his service during World War II.

When growing up, Russell recalls his father sharing little information about his time in the Army during the war even though he would later go on to serve more than 30 years as a battalion commander in the Missouri National Guard.

“I spent a lot of time with my father at the armory in Mexico when he was in the (National Guard),” said Russell’s son, David. “But he really kept quiet about his service in World War II, so I really didn’t know many details of his war experiences.”

Born in 1918 and raised in Kentucky, Peyton Russell graduated with a bachelor’s degree in mathematics from Murray State University in 1940, registered for the draft and began teaching for a local school.

His career in education was interrupted when, according to records accessed through the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Russell was ordered to report for a physical and was subsequently inducted into the U.S. army on October 9, 1941, nearly two months prior to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

The 23-year-old recruit was sent to Fort Benjamin Harrison, Ind., where, he explained in his diary, he was given “a mental test, oath, classification, got uniforms issued … (and received) two shots after eating.”

Several days later, Russell and several recruits boarded a train, arriving at Fort Sill, Okla., on the afternoon of October 15, 1941. That evening, he wrote, “(I) bunked with five others in a tent (and) nearly froze sleeping under two blankets.”

He was assigned to the 32nd Field Artillery Battalion and settled into the routines of Army life for the next three months. This cycle of instruction included equestrian training since mounted soldiers could serve as observers for the field artillery and haul light artillery pieces.

In early January 1942, nearly a month after the United States entered World War II, Russell trained for several weeks at Camp Papago Park in Phoenix, Ariz. From there, he continued his training at Camp Hydle at Point Reyes, Calif., until receiving orders for Alaska in August 1942, boarding a troopship in Oakland, Calif.

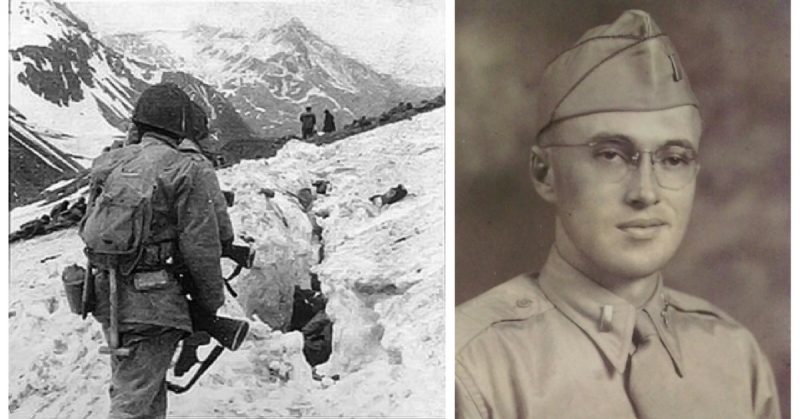

Days later, the battalion disembarked the ship at Adak Island, Alaska. In their camp, the whir of air raid sirens became a regular part of their duty day because of the threat of attack from Japanese planes.

In early October 1942, Russell wrote, “Three bombs dropped within 500 yards and machine gun bullets within 25 feet of my tent.” The following day he scribbled in his diary, “Bombs at 4 a.m., didn’t get up, southwest of camp.”

For several months, Russell remained at his Alaskan duty station performing what he described as “routine Army duties,” much of which seemed to consist of digging drainage ditches. However, on March 31, 1943, he again boarded the USAT St. Mihiel bound for Ft. Lewis, Wash., and then traveled to Ft. Sill, Okla., for officer’s candidate school.

In early 1944, the young second lieutenant was sent to California to complete desert maneuvers with the 491st Armored Field Artillery Battalion and received a promotion to first lieutenant on June 20, 1944. Following a brief period of leave, Lt. Russell and the battalion boarded a troop ship in New York and sailed for England.

The battalion arrived in France in December 1944 and began providing artillery support as the Allied front pushed west into Germany, assisting such entities as the 4th Infantry Division in the recapturing of several cities that had been previously held by German forces.

Russell’s diary in the spring of 1945 chronicles the passage of the battalion through various German communities and, on May 6, 1945, he wrote of their arrival at a “gasthaus” (German-style inn) near the small Austrian city of Gallneukirchen. It was here, he stated, “we enjoyed the end of the war … picking up saddle horses to ride shows” in addition to “souvenir pistols.”

In the months that followed, Russell was transferred to the 144th Field Artillery Group and served with the occupying forces until returning to the United States in December 1945. He was discharged from the Army in early 1946 and, in June the same year, moved to Mexico, Mo., to take a job with A.P. Green Firebrick Company until retiring in 1983.

The veteran married in 1949 and later enlisted in the Missouri National Guard. He retired from the National Guard at the rank of lieutenant colonel with more than 30 years of service to his credit. Sadly, the veteran passed away on December 11, 2003 and was laid to rest in Elmwood Cemetery in Mexico.

While growing up, David Russell recalls spending time with his father as he performed his duties at the Missouri National Guard armory in Mexico. Despite the time they were together, David explained, his father rarely discussed his WWII service but offered a glance into his early military service through his diaries.

“I don’t think he talked about it much because he likely didn’t think his service was all that interesting or as important as the soldiers who participated in D-Day, the Battle of the Bulge or other major battles,” said David Russell.

“It was certainly not that he was ashamed of his service in any way, it was that he was a very humble man. Because of this,” he added, “I really didn’t know much about that period of his military career and this is why it is important for veterans to share their stories before they are lost.”

He concluded, “I am glad he kept a diary because it helped me to understand what he did during the war and ensures his story is in some way preserved.”