War History Online Presents this Guest Article by Frank Jastrzembski – www.frankjastrzembski.com

Josiah Tattnall cringed as he watched the helpless British steamboats catch fire one by one from the well-directed fire of the Taku Forts. He could not help but feel sympathy for his English counterparts.

Tattnall was serving as the Flag Officer of the United States East Indian Squadron, and acting as part of an Anglo-French fleet sent to the mouth of the Pei-Ho River on June 21, 1859.

He had specific orders from the U.S. government to remain neutral toward the Chinese, even though the British and French intended to take an aggressive diplomatic approach.

Born in Georgia in 1795, Tattnall entered the U.S. Navy in April of 1812 as a midshipman at the age of seventeen. Destined for an apprenticeship in the medical profession, he chose instead to pledge his life to the sea. He became notorious for his rash behavior.

Following the War of 1812, he hunted down privateers in the Caribbean for a number of years. In one noteworthy incident, while in Valparaiso, Chile, he challenged a British officer to a duel who insulted his country, shooting the offender in the leg.

At the siege of Veracruz during the U.S.-Mexican War, he received praise for “his most noble and heroic conduct.” While aboard the Spitfire, he came so close to the castle of San Juan D’Ulloa that Commodore Matthew Perry had to order him back at the risk of losing his vessel.

Tattnall reluctantly pulled back, reportedly exclaiming in disgust, “Not a man killed or wounded!” For his brave conduct during the war, members of his home state of Georgia awarded him a ceremonial sword.

With forty-five years of seafaring experience under his belt, Tattnall was given command of the U.S. naval forces in the East India and China Seas on October 15, 1857. Negotiations with the Chinese had gone from tense to unstable as the British, French, and Americans attempted to force the Chinese to ratify one-sided trade agreements.

Tattnall arrived at the mouth of the Pei-Ho River with his flagship, the Powhatan, accompanied by the recently purchased light steamboat, the Toey-Wan.

The Pei-Ho was too shallow to allow the Powhatan to travel up the river, leaving the Toey-Wan as the only American vessel able to transport the American minister with a message from President James Buchanan to Peking. At the mouth of the river, Tattnall met twenty-one Anglo-French steamboats under the overall command of Admiral John Hope.

At the head of the Pei-Ho River lay the Taku Forts garrisoned by Chinese soldiers. To his dismay, Admiral Hope discovered that barriers had been built across the mouth of the Pei-Ho, blocking access upriver to Peking.

Hope intended to muscle his way through the obstructions when the Chinese defenders refused to remove them. Hope rammed one of the barriers with his gunboat, the Plover, cutting a path through which the remainder of his light steamboats and gunboats could pass.

The Chinese replied by opening fire from the forts on both sides of the river. Within fifteen minutes, Tattnall knew that the British vessels would be all but destroyed by the crossfire of the forty guns that reigned down upon them.

Only nine of the forty men on the Plover remained capable to tend to their guns, causing Hope to row while under fire to the Opossum to resume the fight.

Within a short time, Hope was wounded when a shot smashed into the Opossum, propelling an iron chain into the air and smacking him in the side of his body, causing him to break three ribs. Though disabled, Hope remained lying on the deck until he ordered his men to move him to the Cormorant.

Tattnall and his American sailors sat aboard the Toey-Wan out of harm’s way observing these events unfold. Reserve boats loaded with British sailors drifted near Tattnall’s vessel, unable to row to their countrymen’s aid due to the strong tide.

A British officer came aboard the Toey-Wan to report the desperate situation to Tattnall. Unable to bear the butcher any longer, he shot back to the British officer’s delight, “I’ll tow your reserves into action. Blood is thicker than water!”

Defying the neutrality that existed between the Chinese and his county, Tattnall towed the British boats into the hottest point of action. He left the Toey-Wan aboard a small barge with a handful of picked men and rowed up to the Cormorant.

A Chinese shot hit the barge, and John Hart, described as “one of the finest seamen who had ever served,” was hit in the side of the head and knocked unconscious by a splinter from a shattered oar.

He died from the wound, destined to be the only American fatality. Tattnall greeted the protracted Hope as if in a parlor rather than under intense fire, offering his services to Hope, “apart from actual engagement in battle.”

Tattnall’s small barge soon sunk from the Chinese shot that had struck it. He was forced to catch a ride with a passing British steamboat back to the Toey-Wan. As he was about to board the British vessel, he turned around and noticed his sailors were manning a British gun and returning fire on the Chinese forts.

“What do you think you are doing,” he asked, “Don’t you know we are neutrals?” One bold sailor proclaimed, “Began you pardon, sir, they were very short handed at the bow gun, sir, so we gave ’em a help for fellowship’s sake.”

Despite Tattnall’s efforts, the shattered Anglo-French fleet lost the battle. Six British vessels were sunk and an amphibious invasion repulsed. The next morning, Tattnall offered to transport two launch loads filled with wounded men from the battle to safety.

Despite his breach of neutrality, Tattnall was not reprimanded by his government. The British minister conveyed an official “thanks of her majesty’s government and the Lord commissioners of the admiralty for the assistance thus rendered her majesty’s service.” Tattnall returned to the United States after the battle.

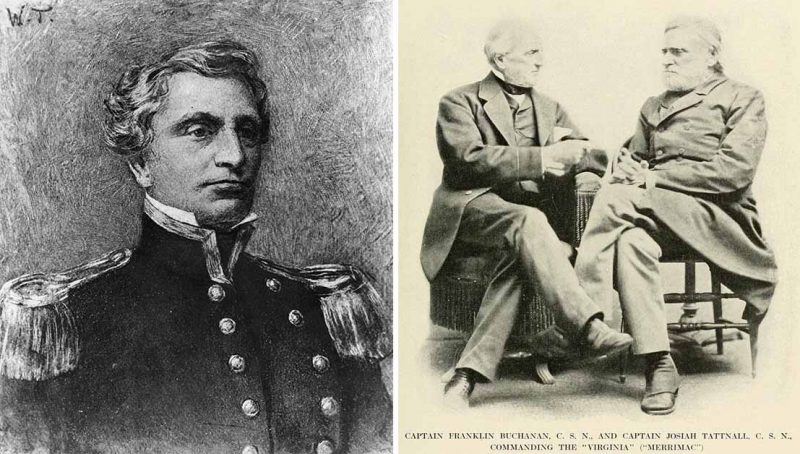

In 1861 with the outbreak of the American Civil War, he opted to join the Confederate Navy, earning censure for ordering the destruction of the famed ironclad, the CSS Virginia.

He died in June of 1871 and is buried in Savannah, Georgia.

Author: Frank Jastrzembski

Further Reading

- Bocock, John Paul. “Blood is Thicker Than Water.” Munsey’s Magazine 22 (October 1899-March 1900): 85-92.

- Boot, Max. The Savage Wars Of Peace: Small Wars And The Rise Of American Power. New York: Basic Books, 2002.

- Curtis, Edith R. “Blood Is Thicker Than Water.” American Neptune 27 (1967): 157-176.

- Jones, Charles C. The Life and Services of Commodore Josiah Tattnall. Savannah: Morning News Steam Printing House, 1878.

- Ward, L. McIntosh. “The First American Embassy to Pekin.” The American Magazine 9, no. 1 (November 1888): 23-31.