School football rivalries have long existed, and harmless pranks typically accompany them to boost team and school morale. This is true of the rivalry between the US Military Academy West Point and the US Naval Academy. After years of having their mascot stolen, a group of Naval Academy midshipmen took on one of the greatest mascot-kidnapping missions in military history: the theft of West Point’s treasured mules.

Kidnapping Bill the Goat XXVII

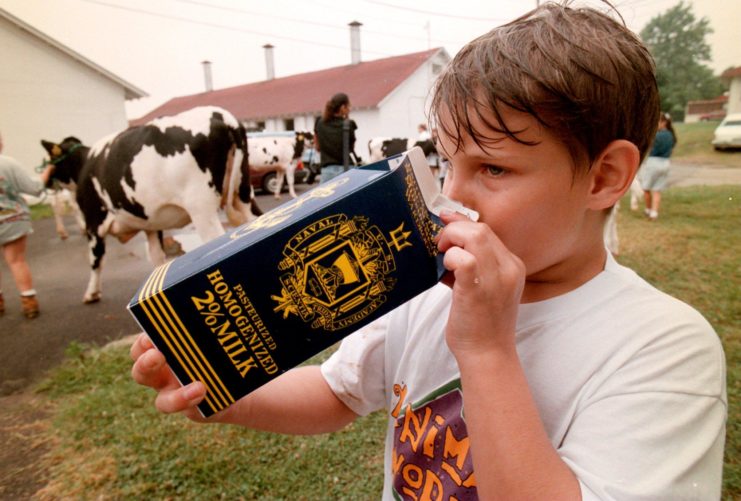

West Point kidnapped Bill the Goat XXVII from the Naval Academy in 1953. Two cadets, Ben Schemmer and Alex Rupp, planned the heist and broke into the Naval Academy’s dairy farm to grab the goat. The farm had been operated since 1911, and was located 20 miles off campus, making it an easy target to infiltrate.

Acquiring the help of another cadet who owned a soft-top convertible, Schemmer and Rupp loaded Bill into the backseat, but not before sedating him with chloroform-soaked rags. They sped off back to West Point, evading those on the lookout for the mascot. When they arrived back to campus, they paraded Bill around the mess hall while the other cadets cheered.

Word spread fast as to who stole Bill, and US President Dwight D. Eisenhower, a West Point graduate himself who’d played on the school’s football team in 1912, ordered the goat be returned immediately to the Naval Academy.

The capture began a new football tradition, one that would hit its pinnacle in 1991 when 17 midshipmen set forth to capture all four of West Point’s mule mascots. The meticulously-planned heist was dubbed “Operation Missing Mascot.”

Preparing to steal the US Military Academy West Point’s mules

Planning for Operation Missing Mascot began in January 1991. The group agreed they needed vengeance for the stunt pulled by the West Point cadets decades prior. They were also aware of the difficulties they would face trying to capture four mules.

The LOG, a humorous magazine run by the Naval Academy, wrote, “Stealing Bill the Goat is one thing. A small farm animal weighing 100 pounds is led out of a remote barn some 20 miles from USNA. An Army mule weighs over one thousand pounds and has to be specially transported … Of course, that is if one can even get on base and successfully infiltrate where the mules are kept.”

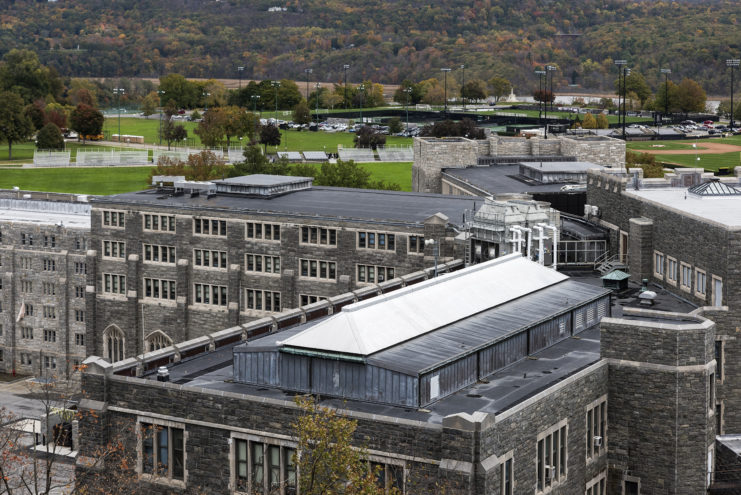

The biggest issue was that the pen where the four mules – Ranger, Trooper, Traveler and Spartacus – were kept was located in the heart of West Point’s campus. The midshipmen wanted to keep the mission as humane as possible and added Weir “Tennessee” Denton to their team, a 67-year-old retired mule farmer who used to work at the Naval Academy’s dairy farm.

A mule farmer joins Operation Missing Mascot

Weir Denton was at the dairy farm when West Point cadets captured Bill the Goat a few years prior to the 1953 heist, in the early ’40s. That time, they’d released dairy cows from the farm, and as Denton and others tried to round them up, the cadets stole the goat. When the midshipmen asked him for his help, “Tennessee never forgot that night and leapt at the opportunity to avenge Army.”

A friend of the midshipmen who carried out Operation Missing Mascot, Dan Goldenberg, recalled how important the care of the mules was to those creating the plan. “The guys were determined to do it right and take good care of the animals,” he said. “If you talk to any of the guys who did this, they’ll all talk about being trained how to properly handle the mules.”

Other preparations outside of mule handling included midshipmen entering West Point’s campus dressed as tourists to take photos and gather intelligence. They even fed sugar cubes the mules they were planning on kidnapping.

The first attempt at Operation Missing Mascot failed

The team decided to carry out the mission on November 29, 1991. It began as their intelligence gathering had. The midshipmen dressed as tourists and infiltrated West Point’s campus. However, this time, they were equipped with communications gear that allowed them to stay in contact with one another.

Over the course of the morning, they slowly gathered on the football field located about 100 yards from the pen where the mules were held. They intended to sneak into the area during feeding time, but after a few hours realized the scheduled feeding must have occurred earlier than normal. The midshipmen eventually abandoned the mission for that day.

Following this, the team held a secret meeting on December 3, where it was decided they would carry out a second attempt the following Thursday, December 5. The participants had to change due to it being carried out on a weekday, but they were able to make the necessary replacements and follow through with the short-notice plan.

Infiltrating the US Military Academy West Point

On December 4th, 1991, the new team of 17 gathered at a motel outside of West Point. They dressed in Army uniforms that bore the Army enlisted insignia and military police gear, and divided into two assault teams: Alpha and Bravo. Each had an assault leader, method of entry (MOE) specialists, intelligence and electronics specialists, man handlers, and a door man. There was also a mule-handling team.

The LOG wrote of that fated morning, “Their task: in less than three minutes they were to catch, put in a headlock and then bridle these animals. And of course, all this was to be done in broad daylight – and in the words of the team leader, ‘Look natural and do not draw attention to yourself.'”

When they reached the campus at 9:15 AM, they slipped easily past the unguarded gate and made it to the mule pen four minutes laters. The Alpha team leader convinced a sergeant to let them through the front door after explaining how they were there to load mule feed. From there, they began to lead the animals from their pen to the vehicle.

They couldn’t hide their intentions for long, and the sergeant soon realized what they were trying to do. He yelled, “Call the MPs,” but it was futile, as the handlers restrained the sergeant and others with zip ties and used duct tape to silence them.

“Like clockwork, prisoners were interviewed for knowledge of alarms and MP patrols and, at the same time, the mules were being loaded into the barn from the outside pen,” The LOG explained. In under one minute, the mules were loaded onto the vehicle and the assault teams were ready to retreat.

Operation Missing Mascot almost failed

Other cadets noticed the commotion and realized what was happening. As they hadn’t been taken prisoner, some tried to warn others about the intruders, while the rest attempted to chase them down. The vehicle housing the mules successfully made it off of West Point’s campus by 9:53 AM, but, by this point, the federal and state authorities had been notified. Even three West Point Bell AH-1 Cobras were deployed to help search for the midshipmen.

Instead of driving the mules straight to the Naval Academy, the group drove to Anne Arundel County, Maryland. They remained there until the scheduled football pep rally at 7:30 PM that evening. The midshipmen arrived on campus at 7:15 PM and were met by the federal authorities, who’d figured out who was responsible for the heist.

“We were removed from our vehicles and spread-eagled on the baseball backstop,” the chronicler for The LOG wrote. “It seems we were guilty of grand theft mule.”

A loophole saves the midshipmen

All hope wasn’t lost, however, as the Naval Academy’s command duty officer convinced the authorities to take the midshipmen onto campus by police escort. By doing so, she was able to trick the authorities into entering Naval Academy property. As soon as they entered the campus, she said, “Get the hell out of here, you have no jurisdiction.” The midshipmen had gotten away with it and were able to hold onto the mules for the pep rally.

The following day, the Naval Academy were victorious against West Point’s football team. Surprisingly, the latter never pressed any charges, but the seriousness of what had been done wasn’t overlooked.

Bill Wiseman, a senior who participated in Operation Missing Mascot and later served as a US Navy SEAL, said, “Looking back, we went so far overboard, tying guys up. You would never get away with that today. I’m frankly amazed we didn’t get in a lot of trouble.” Instead of punishment, the midshipmen were awarded “The Order of the Mule.”

More from us: Most Anticipated War Movies of 2023

The schools eventually called a formal truce, but the kidnapping went down in the annals of Naval Academy history as a victory, while also going down in West Point history as a major failure.