Over 100 years ago a refugee crisis was going on in Europe that mirrors what is happening in our own time. People were fleeing Russia, Serbia, and Armenia. Belgium alone saw an exodus over 1.5 million.

In August of 1914, Germany invaded neutral Belgium to set up a pathway to France as part of the Schlieffen Plan.

Stories of the German invasion of Belgium reached England featuring stories of horrible atrocities. There was a great outpouring of concern from the British people, and because of a treaty made in 1839 that the Brits would defend Belgium’s right as a neutral nation to deny passage of warring nations, Britain declared war and began making preparations to take in Belgian refugees.

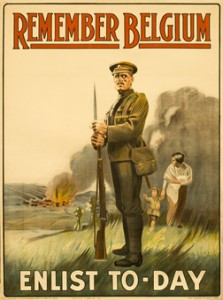

Viscount James Bryce had compiled a report known now as The Bryce Report that alleged terribly violent acts committed by the Germans against the Belgians. It detailed rapes, murders, the killing of children, massacres, fires, and looting. Some historians mark it as propaganda, but the report claims to have gotten its information from first-hand accounts and the diaries of German Soldiers. However it was it intended, it was indeed used as propaganda in Britain and the United States to gain public support for declaring war against Germany.

Following the invasion, one in five Belgians was leaving for safer havens. Most went to the Netherlands and France, with estimates as high as 260,000 seeking refuge in Britain. The rest went far afield to the U.S., Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Spain, Cuba, and Switzerland.

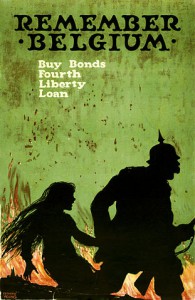

Posters went up all over England that read “Remember Belgium”, “The Rape of Belgium”, “Remember the Women of Belgium”, all of which entreated men to “Enlist Today”. Belgium was referred to as Gallant Little Belgium and its people as “plucky”.

The British government wasn’t sure how to organise the refugee crisis and find housing. The Home Secretary was looking to build camps in Ireland, not certain just what to do. Winston Churchill, then the First Lord of the Admiralty, said they “ought to stay there and eat up continental food and occupy German policy . . . this is no time for charity.”

While the government was uncertain about logistics, the public was clamouring for Belgians to keep in their homes. Several sources liken the sentiments of the civilian population as viewing the refugees as pets. Every home wanted one.

Luckily for the refugees, the government found ways to accommodate them temporarily before going to communities that had volunteered to take them. Skating rinks, public buildings like Alexandra Palace and Earl’s Court, and other similar places were set up as short term housing.

When they arrived, they often arrived in great numbers. One port reported 26,000 at one time.

As many as 2500 committees were formed to help the national and local governments to organise the effort, including official Belgian organisations like the Belgian Legation. Charities were established, and fundraisers held to help in the effort. The Catholic Church set up schools to educate the children in their languages and according to their religion.

The open arms welcome they received in the beginning was heart-warming and full of charity. Poetry was written; paintings were done of the well-heeled British greeting the bedraggled refugees at port with British children offering plates of cookies. Writers like Virginia Woolfe and Agatha Christie were inspired by the refugees. Families posed for photographs with their new refugees, beaming with pride at their own generosity. Brits that took in refugees thought of themselves as upstanding contributors to the war effort.

Everyone thought the war would be over by Christmas and that their new friends would then go home, back to their lives in Belgium grateful for all that had been done for them.

But the war carried on.

As it did so, the previously altruistic volunteers began to resent the Belgians staying with them. The cultural differences led to animosity. Belgians ate horsemeat, drank alcohol at times the British saw as inappropriate, their women didn’t wear hats in public. Rumors and comments regarding the entitled attitudes of the Belgians abounded, one regarding a refugee that paraded about calling himself a duke.

The people who viewed them as pets from the beginning now openly referred to them as “spoiled pets”. Some called them “the Belgian atrocities”. Love was being lost quickly.

Adding to the tension was the second wave of refugees.

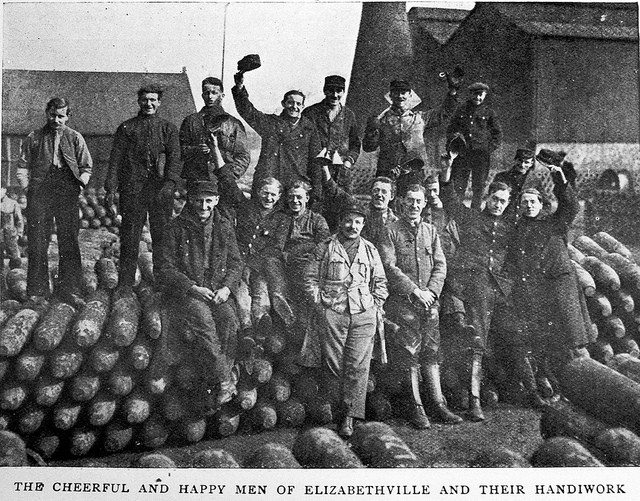

This time around, it was the British government that took full command of bringing in refugees to work in munitions plants. Britain was fast running out of explosives and needed fast turn-around in the factories and so brought in refugees that were tiring of the conditions in the refugee camps of the Netherlands. They had heard that Belgians in Britain were living normal lives in homes in British towns and villages rather than in overcrowded refugee camps. They were more than ready to come across the channel and work hard.

The Belgians were required to register with local police, carry identification, and keep the police apprised of any moves or changes in their personal circumstances. If they did not, they were threatened that they would be seen as enemy aliens from Germany.

The British government built them fully functioning towns around munitions plants. Some were designated as official Belgian colonies and were sovereign. The government helped married men find and relocate their wives and families to their new homes. They were provided with English language classes. They had houses, stores, and places of entertainment. They also had running water, electricity, and even indoor toilets – things the nearby British neighborhoods didn’t have.

Though they worked hard and contributed much to art, building, and the war effort, the nearby villagers began to resent fully that the Belgians were well fed and lived nicely while they were suffering.

In reality, while the Belgians did have comfortable homes, their society, and were doing well in comparison to those back home, they worked in munitions plants. TNT caused terrible health problems and injuries, and even death came from working with explosives and in industrial environments. Riots broke out due to political tensions between refugees speaking different languages, and from friction from trade unions upset at the Belgians for accepting lower wages and terrible working conditions.

They also faced disregard and condescension not only from the people of Britain but from the government. Newlyweds weren’t allowed to live together until they showed that they could demonstrate English lifestyles. People suspected the men of being German spies and were very wary of Belgians that did not enlist in the war. Belgians in London were beaten by men that believed they were German spies.

Some communities that had taken in refugees complained that the Belgians viewed the charity as their right and expected more than what was freely given, even to the point of wanting more than what the British themselves had. The refugees were now seen as ungrateful and lazy. The anti-Belgian sentiment was rising so much that riots broke out in protest of refugee support.

The war and the tension lasted four years. When it ended, Britain could not merely send them home immediately, although the government and the people wished it to be so. First, however, the soldiers had to be brought home and cared for, and the Spanish Influenza epidemic managed.

When it was time, the government lost no time in getting things done. The second wave munitions workers were sent back first because they were skilled workers that could rebuild Belgium and have it ready for other returning refugees. The remainder was given limited time free transportation while at the same time having their aid cut off. All but 9800 of them returned to Belgium, and quickly. Sadly, they were not received well at home, either; being seen as somewhat traitorous for having sought safety abroad rather than remaining at home for the fight.

Some British families did form strong bonds with the refugees they supported and remained in contact with them after the war, having reunions and sending correspondence to keep in touch. Many married Belgians who then chose to remain. The King of Belgium awarded the Medaille De la Reine Elisabeth to the volunteers of the town of Preston for their support of refugees and Belgian soldiers.

The temporary towns they occupied in Britain became ghost towns in the beginning. Slowly, they became free unauthorized housing for the indigent until the 1930s when they began to be torn down. Elisabethville, the most famous colony, even lost its cemetery to time, without even the headstones to mark the graves.

The refugees are mostly forgotten in Britain, but websites and societies remain to help descendants and those interested in history to learn more about that time and the people who lived it. There are memorials and statues, and the finer work that they created, but for the most part, they only remain in traces within photographs and archived diaries.

For a look at how they are remembered by those that do, this video is about an Irish town looking for the descendants of the Belgians that contributed to lasting prosperity in their town.

Sources:

- Paxman, J. (2014). Great Britain’s Great War. Penguin Books, Limited.

- http://belgianrefugees.blogspot.com/2013/12/jeremy-paxmans-great-britains-great-war.html

- http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-28857769

- http://www.bl.uk/world-war-one/articles/refugees-europe-on-the-move

- http://www.mylearning.org/preston-takes-in-wwi-belgian-refugees/p-4624/

- Christophe Declercq – Belgian Refugees in Britain –http://www.onserfdeel.be/frontend/files/userfiles/files/BelgianRefugees%202.pdf

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Birtley_Belgians

- http://beyondthetrenches.co.uk/remembering-elisabethville-the-belgian-refugee-colony-of-durham/

- http://www.bbc.co.uk/guides/zcn3b9q

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Committee_on_Alleged_German_Outrages