During his service in the U.S. Army’s first African-American regiment in WWI, Henry Johnson survived an epic battle against German enemy soldiers – a fight that left him with an astounding 21 wounds

It was at midnight in the Argonne Forest when Henry Johnson heard the sounds of German troops. He stayed put, ready to defend his army. He stayed close to Needham Roberts, a comrade who was equally fighting the fierce cold in the heart of the night. Both had just arrived in Germany under the France troops.

Johnson closely monitored every step made by the German troops. In the next two hours, the duo remained silent, watching the troop’s movements.

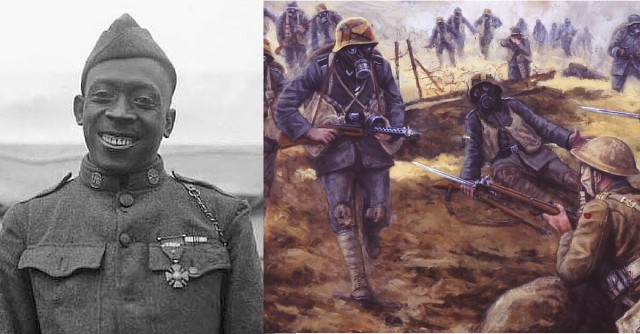

At 2 a.m., the German troops started lobbing grenades at the post where Johnson and Roberts were stationed. The Germans planned to capture some or all of the troops that had just arrived from U.S.A.

Johnson and Roberts fought fearlessly. By and by, Roberts was shot in the knee and disabled. However, Johnson stood his ground. He used the three bullets he had in his rifle and shot at the invading German troops.

Johnson ran out of ammunition. Yet he could not give up. Not until he saved himself—and his comrade-in-arms. He needed to make a quick decision on what else he could do. Quickly, he held his gun tightly. As the Germans got closer to the two, Johnson used his rifle butt to fight them. He mastered all his energy and directed the butt to one German soldier, hitting his head and killing him instantly. When he realized that worked, he used the butt again and hit another soldier. That one, too, died instantly.

As if not enough, Johnson saw other soldiers trying to carry Roberts away. Although he was already injured with gun wounds and grenade injuries, Johnson knew he couldn’t give up. He again attacked the Germans. He killed another German soldier and injured scores of them.

The Germans didn’t give up. One German shot Johnson in the stomach. Johnson fought back, cutting the soldier with a knife. Roberts, although injured and in pain, gave Johnson grenades. Johnson threw the grenades at the retreating Germans. Incidentally, the attacking German unit consisted of not less than twenty-four heavily armed men. In the fierce fight, Johnson killed at least four Germans and wounded more than eight others.

The battle had been so fierce that after the Germans retreated, Johnson fainted from shock. Two hours after the attack, Johnson and his comrade-in-arms Roberts were taken to a field hospital. Johnson suffered injuries on his left arm, back, feet and face, most of which were caused by knives and bayonets. He had a total of twenty-one wounds. Johnson and Roberts were put under treatment.

While in the French hospital, Johnson thought about his early life.

Henry Johnson (aka William Henry Johnson) was born on July 15, 1892 in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, according to his draft papers. Venturing out on his own in his teenage years, he moved to Albany, New York to work tirelessly as a redcap porter at the Albany Union Station. However, that all changed the day Johnson decided to join the United States Army.

From Everyday Harlem to the Trenches of War

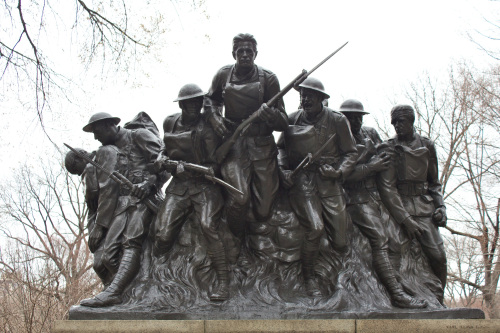

On June 5, 1917, Johnson enlisted and joined the all-black New York National Guard, 15th Infantry Regiment. Stationed in Harlem, the Regiment soon became the 369th Infantry regiment when reassigned in the Federal Service.

Planning to set off for France to join the war efforts, Johnson and his fellow soldiers were met with many trials and tribulations just trying to leave the harbour. Months of attempts and failures to cross the Atlantic tampered the men’s spirits, and damage due to a collision with another ship in bad weather almost derailed the journey altogether. However, at the command of Colonel William Hayward, the men repaired the ship themselves and eventually set sail for France. By the end of December 1917, the regiment had finally arrived.

However, engaging in the war was only one of many battles Johnson was forced to endure during this period. Unfortunately, he entered the army during a time of blatant racism and bigotry amongst the white American and African-American troops, with discriminatory behaviour prevailing all the way up the commanding line.

While Johnson was still in Harlem, the then 15th infantry of the New York National Guard had been the first all-black regiment to be instituted in the army. However, this regiment was still led by white officers. To create change, an African-American New Yorker by the name of Charles W. Fillmore had introduced the idea of an African-American unit. The governor at the time, Charles S. Whitmore, ultimately decided in favour of the idea, appointing Colonel Hayward to take charge of creating the regiment. For his efforts, Fillmore was then commissioned by Hayward to become Captain.

Despite making headway in the advancement of African-Americans in the army, racist undertones still burdened the war effort. Once the troops had landed in France, Johnson and his fellow regiment were initially detained from combat training, instead merely delegated to labor service duties. Under the command of General John J. Pershing, Johnson and the 369th regiment were apparently ‘loaned’ out to the French army’s 161st division. According to speculation, Pershing made this decision to segregate the African-American troops as a result of the Caucasian soldiers expressing their grievances regarding working next to their black American comrades. Racism amongst early American military forces led to decades of struggles in trying to honor Johnson’s legacy later on.

While turmoil amongst the American infantry was going strong, the French army had a decidedly different approach to their arrival. French soldiers and citizens welcomed Johnson and the Americans, merely being thankful for any reinforcements they could acquire as the war continued to rage on.

A Hero is Born

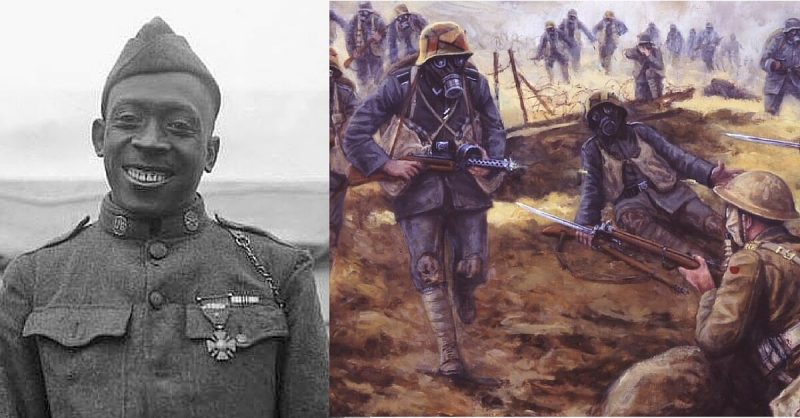

For his valiant efforts, Private Johnson was awarded the Croix de Guerre, a French medal with a star and bronze palm. He was the first American soldier in WWI to achieve this award, and wore it proudly among the other soldiers of the 369th infantry, who later became known as the “Harlem Hellfighters.”

Newly-appointed Sergeant Johnson returned home as a national hero, gaining recognition through his story published in the Saturday Evening Post and New York World. Johnson and his regiment were invited to partake in a victory parade in New York City, and he began a lecture tour around America.

However, when it came time for Johnson to describe the unity among his fellow soldiers, he could not hold back the truth: during a lecture in St. Louis, Johnson detailed the abuse of African Americans at the hands of white soldiers, describing the racial segregation.

In the weeks after, in response to his comments, Sgt. Johnson became a pariah of sorts. His refusal to hide the truth about the army’s behaviour led to him spending the rest of his life in ambiguity.

Sadly, this remained until the day of his death. On September 16, 1927, Veterans Bureau records show Johnson had been granted disability in response to his diagnosis of tuberculosis. On July 1, 1929, Johnson passed away in Washington D.C. and remains buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Remembering the Honest Man

Johnson’s bravery has been commended through countless awards and recognitions since his last day on the battlefield.

In 1919, he was named by Theodore Roosevelt, Jr. as one of the five bravest Americans to serve during World War I. In Albany, New York, Johnson has accrued multiple acknowledgments, including a monument in Washington Park built in 1991 and a Charter school bearing his name in 2007.

And after posthumously receiving a Purple Heart from President Bill Clinton in 1996 and the Distinguished Service Cross in 2003, Sgt. Johnson most recently received his Medal of Honour, awarded by President Barack Obama on June 2, 2015.