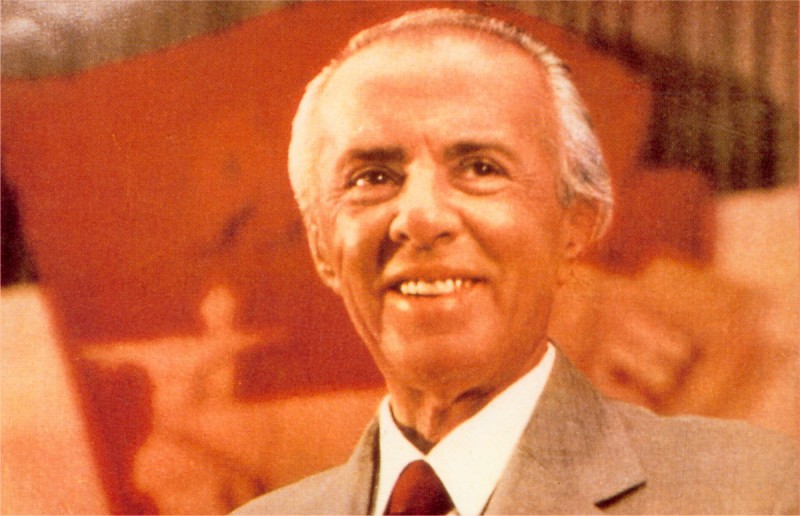

Well-groomed and ramrod-straight, he had a great head of healthy, white hair. He easily could have been marked as a retired head teacher or postmaster. However, Nesti Vako was arguably the most important engineer working under the former Albanian communist dictator infamously known as Enver Hoxha – a paranoid dictator who ordered Vako’s colleagues to build about 750,000 or so bunkers.

For 25 years Mr. Vako worked as head of surveillance for the Sigurimi secret police. There is no denying how important he was. For many Albanians living under Hoxha at the time, the Sigurimi were synonymous with torture, execution, and arbitrary imprisonment. Plus, they knew that the agents resided in the House of Leaves; this is where I met with Mr. Vako.

The old Sigurimi’s headquarters in Tirana, along with Mr. Vako, looked nothing like what I was envisioning. This structure could have been mistaken for a bishop’s residence since it was just a solid red brick house with copper drainpipes and limestone window frames. The name of the house derived from the ivy leaves that covered the front at one point.

Nesti Vako willingly gave a tour of the deserted house that was going to be made into a museum. In fact, some of the exhibitions are already there. This includes a German-built recording machine, bugs in spectacle cases, and broom handles and suitcases with hidden cameras. Some would joke that the only things missing were the lit cigars and a James Bond Aston Martin with pop-up machine guns. Mr. Vako certainly had a creepy history, or resume if you will, but he was likable. He came off as sincere when discussing his role in protecting people from “insurgents” and “terrorists”.

Upon the suggestion that perhaps people needed to be protected from the Sigurimi, Vako bridled resentfully. He said, “The prosecutor general had to sign an order for the surveillance to take place; there was a time limit on how long you could spy on someone. There was nothing illegal.” He did come around to admitting that the communists did make a lot of mistakes.

Mr. Vako explained, “For example there was this crazy system of farm collectivization, when people had their pigs and sheep taken away. But this was not Enver Hoxha; this was just some official attempting to advance his career.” There was another ex-secret policeman on site named Adrian Pepaj who claimed they stopped saboteurs from killing people by blowing things up. During the four-decade reign of Hoxha, the country lived in virtual isolation.

The dictator is now suffering the tyrant’s ultimate embarrassment as he has become a tourist attraction. Like the House of Leaves, his old place of residence is dilapidated in the center of Tirana. There are plans in motion to also make that a museum. Hoxha’s personal nuclear bunker on the outskirts is a large underground cavern which is already open to the public.

Germany likes the initiatives taking place and is even helping to financially support the communist-era relics. The German ambassador to Albania is Hellmut Hoffmann, who deems all of it a good start. However, he expressed some regret that, “None of the original sites where the terror really took place have been turned into commemorative sites. Probably the most notorious forced labor camp, called Spac, about two hours drive from Tirana, is rotting away. They have basically demolished the characteristics of a labor camp and there are no plaques – nothing at all.” Hellmut’s emphasis is on former victims who are looking for more to happen when it comes to commemorating the past.

The Albanian Ministry of Culture is partially run by Genc Bejleri, who oversees the work being conducted at the House of Leaves. He points out that there are some people who lived a relatively easy life under the dictator, but the majority of people genuinely suffered. Under Hoxha, if a father did something considered as bad, then he was labeled as the enemy. But the punishment did not stop there; his sons and daughters would also suffer persecution for the duration of their lives. For example, going to university would no longer be an option.

Albania suffered through plenty of dark days under the dictatorship of Albania, but the country has made impressive strides. A landmark decision was rendered five years ago awarding Albania membership in NATO. Currently, the country is being considered for European Union (EU) membership as well. Since the EU has built new prisons and roads in Albania, it could be said that they are literally “paving the way” for an eventual membership.

However, political corruption and the judiciary are still tied up with the legacy of the past. Albania is working to meet the EU standards, but thousands of people have already left, believing they will be better off living in a different European country.