What began as a routine U.S. Air Force training flight off the coast of Georgia in the mid-1950s unexpectedly turned into one of the Cold War’s enduring mysteries. During a mock combat exercise, a B-47 bomber collided midair with an F-86 fighter. Fearing that an emergency landing could trigger a disaster while carrying a live nuclear weapon, the bomber’s crew made the critical decision to release a Mark 15 thermonuclear bomb into the waters near Tybee Island. The weapon plunged into Wassaw Sound—and was never found.

At the time, military officials sought to calm public concern by claiming the bomb posed no danger, insisting its plutonium core had been removed before the mission. Later declassified documents and expert reviews, however, have challenged that assurance. Some evidence suggests the weapon may still contain nuclear components, raising the unsettling possibility that it remains intact beneath the seabed.

Repeated search operations failed to pinpoint its exact location, and debate continues over whether recovery would be safer than leaving it undisturbed. Shifting sands, erosion, and powerful storms constantly alter the seafloor, complicating any effort to retrieve it. Known today as the “Tybee Bomb,” the lost weapon stands as a sobering Cold War artifact—and a reminder of how narrowly disaster was once avoided.

Mid-air collision over Tybee Island

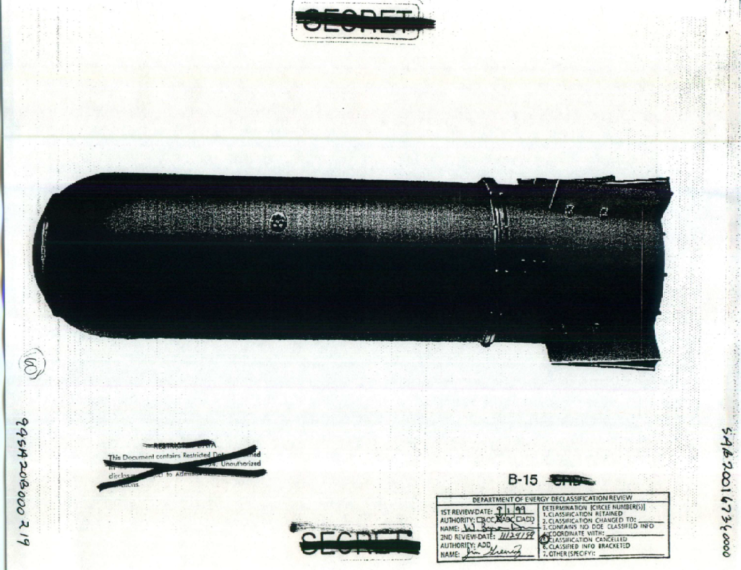

On February 5, 1958, while performing a simulated combat mission exercise, a Boeing B-47 Stratojet was involved in a mid-air collision with a North American F-86 Sabre. The B-47, having taken off from Homestead Air Force Base, Florida, was carrying a two-man crew, as well as a 7,600-pound Mark 15 nuclear bomb.

The F-86’s pilot, Lt. Clarence Stewart, hadn’t seen the B-47 on his radar and descended directly on top of it. The crash between the two caused the left wing of the fighter jet to completely rip off, while the bomber’s fuel tanks suffered heavy damage. Stewart was able to eject before his aircraft crashed, while the pilot of the B-47, Lt. Col. Howard Richardson, sought the closest landing base. Despite the damages to the bomber, the B-47 remained airborne. After dropping 18,000 feet, Richardson regained control.

As for the nuclear bomb onboard the aircraft, he granted the crew’s request to jettison it, to prevent it from exploding during the emergency landing. The bomb was dropped from 7,200 feet, over the shores of Tybee Island. The pilot and crew reported no explosion upon it meeting the water, and they were able to successfully land the damaged B-47 at Hunter Army Airfield, Georgia.

For his actions, Richardson was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.

A search force was sent to find the bomb

Since it went missing, experts have argued over whether the bomb off Tybee Island was actually nuclear. If it had a plutonium core, it would have been a complete nuclear weapon. If not, it likely had a dummy core—meaning it couldn’t trigger a nuclear blast but could still cause a powerful conventional explosion.

The Air Force claimed the bomb’s nuclear capsule had been removed before the flight and replaced with a 150-pound lead dummy. Internal documents from Strategic Air Command backed this up, stating that test flights in February 1958 weren’t cleared to carry nuclear-armed bombs.

That explanation stood for decades—until 1994. A newly declassified document included a 1966 Congressional testimony from W.J. Howard, then Assistant Secretary of Defense. In it, Howard directly contradicted the Air Force’s public stance. He told the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy that the Tybee bomb was, in fact, “a complete, fully functional bomb with a nuclear capsule” that included a plutonium trigger.

If Howard’s testimony is true, the bomb could still be extremely dangerous. A detonation would create a fireball over a mile wide and thermal radiation that could be felt up to 10 miles away.

Yet another search is launched

In 2004, armed with fresh information, Air Force veteran Lt. Col. Derek Duke privately conducted a new search for the long-lost nuclear bomb off Tybee Island. With a small team, he methodically combed the waters of Wassaw Sound, using a Geiger counter to detect any unusual radiation levels.

Their survey revealed that radiation readings near the island’s peak were about four times higher than normal—a potential sign that the Mark 15, if still armed, might be nearby. By tracing these elevated levels, the team was able to outline a target area roughly the size of a football field.

However, an Air Force review of the findings determined the radiation spike was likely due to natural causes, specifically monazite-rich sand deposits. As a result, the bomb’s precise location remains a mystery to this day.

Best to leave the nuclear bomb alone

The Air Force is content with leaving the bomb’s location a mystery, and officials have assured residents in the surrounding area that it poses no threat, so long as it’s left alone. An “intact explosive would pose a serious explosion hazard to personnel and the environment if disturbed by a recovery attempt,” they stated.

More from us: Mars Bluff Incident: The US Air Force Accidentally Dropped a Nuclear Bomb on South Carolina

The next time you go diving near Tybee Island, keep an eye out for the 12-foot long, 7,600-pound Mark 15 nuclear bomb with the serial number 47782. If you spot it, leave the sleeping beast alone!