Greek fire was a real weapon which has achieved near-legendary status. An incendiary device deployed against advancing Arabs by the defenders of Constantinople; it became famous for its devastating impact.

The method used to make the weapon was lost, and later imitations seldom replicated its power.

What was Greek fire and how did it fit into the history of war?

What Was Greek Fire?

Greek fire was a flaming liquid. When launched against an enemy’s ships, it set them on fire with an intense flame that was extremely difficult to quench. It could devastate a fleet or a troop of soldiers.

The most famous and strategically important use of Greek fire took place in 672AD. Ships from Constantinople used it against an enormous Arab fleet which threatened to overwhelm the city. By defeating the Arabs, the Byzantines halted the westward advance of Islam and saved their city for another seven centuries.

We do not have a record of how the incendiary used that day was made. Centuries later, the chronicler Anna Comnena recorded that the fire was indeed used.

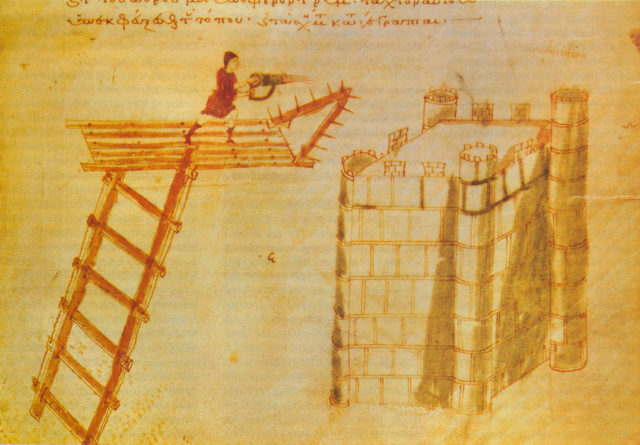

She understood other incendiary weapons used by her fellow Byzantines. One such example was a blowgun using combustible resin and sulphur, but she did not have the recipe for the fire used in 672AD.

The majority of modern scholars who have studied it believe the liquid used was probably a combination of quicklime and naphtha or turpentine.

Quicklime becomes incredibly hot in contact with water. On contact with sea water, it created enough heat to ignite the inflammable naphtha or turpentine. Lighter than water, this burning liquid would have stayed afloat and burning as the Arabs struggled to put it out.

Where did Greek Fire Come From?

Little is known about the invention of Greek fire. One thing that seems clear is that it was not invented by the Greeks, but was imported from the Middle East.

The arrival of Greek fire in Constantinople is attributed to Callinicus, an architect from Heliopolis in Syria. Having seen his home region overrun by the fast and aggressive expansion of the early Islamic empire, he fled to Constantinople. Arriving there in 660AD, he brought the recipe with him.

Only a few decades old, Islam and its adherents were tearing through the eastern Mediterranean at an incredible rate. To men like Callinicus, it looked as if this new faith-fuelled empire threatened the existence of Christendom. He hoped his weapon could turn the tide.

Callinicus’s hopes proved well founded. He provided the Byzantines with the recipe, and they were able to halt the Arabs.

How was Greek Fire Used?

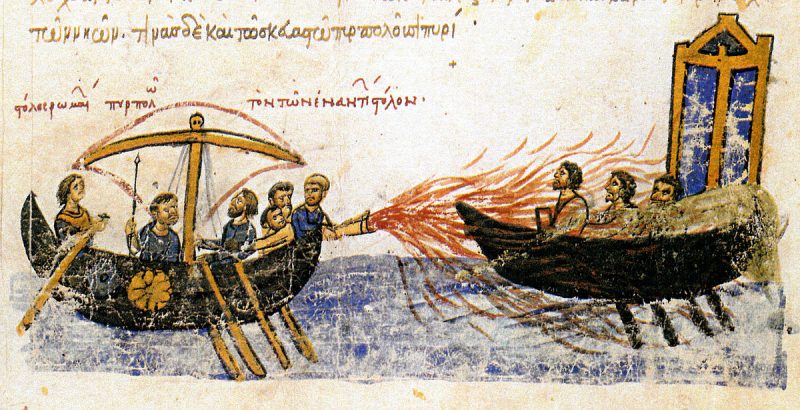

Our best source for information about the Byzantine military and the source of our most detailed description of Greek fire in action is Anna Comnena. Writing centuries after the event, she described how the ships were specially fitted out for the battle of 672AD.

Each ship was equipped with a metal sculpture of a lion or other beast at its prow. These were composed of iron and brass, with terrifying visages around open mouths.

To an approaching enemy, they would have looked like a piece of elaborate Byzantine ornamentation, meant to unnerve enemies and emphasize the strength and ferocity of the fleet.

Rather than wait for the invaders to come to them, the ships sailed out of the harbor to prevent the Arabs getting into the city. The ships with the metal sculptures took the lead. As the fleets grew close, Greek fire was pumped along tubes running through the gilded beasts, spraying out of their mouths and across the Arab ships.

The animals seemed to spew fire across the startled invaders. Many ships were set alight. Unable to extinguish the flames, the survivors turned and fled. Constantinople was saved.

Why is Greek Fire Not Better Understood?

In the days before modern weapons technology, bows and slings were the only alternatives to deadly close quarters melees. The psychological effect of Greek fire was as devastating as its physical impact. It gave the Byzantines a huge advantage, and they kept its recipe a closely guarded secret.

Though the deployment of Greek fire remained relatively rare, the Byzantines made sure to keep fire in their arsenal. There is a record from 900AD of a fire launched from tubes which created vast noise, smoke, and destruction, burning any ships it hit.

Centuries after the fight which made Greek fire famous, Anna Comnena was still writing about this Byzantine weapon, as well as recording the fire-spewing blow gun.

Like the atomic superpowers of the Cold War, the rulers of Constantinople kept the construction of their weapon a closely guarded secret. No-one else was able to replicate the recipe.

Then came gunpowder. Now everyone could access weapons of fire and destruction. The Byzantines themselves turned to gunpowder, and Greek fire became a curio of the military past.

Its recipe was forgotten. If it was written down, the recipe has since been lost or remains hidden away in the corner of an archive, waiting to be discovered by future generations of historians.

Later Imitations

Due to its terrifying capability, the concept of Greek fire seized the imaginations of men who had never seen it in action. When the European Crusaders fought against Islam from the 11th century onward, they sometimes found themselves attacked with fire weapons.

The chronicler Jean of Joinville recorded a barrel-sized container with a tail of fire that was fired from a catapult, exploding in a burst of flames. Faced with a fire weapon in the exotic east, he assumed it was Greek fire.

In reality, this was probably a barrel of naphtha – a generic term for petrol, coal, and natural gas derivatives.

With a fuse lit at one end, it would smash open on impact, and the contents ignite. A less chemically sophisticated weapon than Callinicus’s one, but still deadly.

The legend of Greek fire lives on to this day, and weapons like it have been invented, such as napalm.

Source:

- William Weir (2006), 50 Weapons that Changed Warfare.