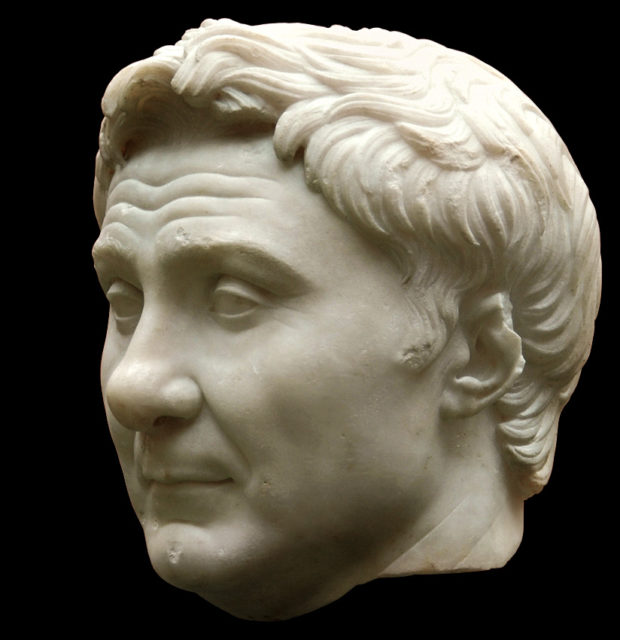

Cnaeus Pompeius Magnus (c.106-48 BC) is remembered as Julius Caesar’s sometime ally and later enemy in both politics and war. Pompey, who Pliny compared in his military skill to Alexander the Great, was a formidable commander in his own right.

Origins

The son of Cnaeus Pompeius Strabo, Pompey came from a family of influence but not huge status. His father was wealthy and had served in the official positions of quaestor, praetor, and consul. They were not a part of Rome’s established aristocracy. Pompey himself had never held any public office when, at the age of 23, he first raised an army.

The Unelected General

In 83 BC, Rome was being torn apart by civil war. Pompey, using the fortune left to him by his late father, raised three legions from his family’s estates and the veterans who had fought for his father. Pompey had served on his father’s staff, and so had some experience of military command.

Roman generals were usually elected, but these were unusual times. Siding with Sulla, Pompey fought well in Italy, Sicily, and North Africa, bringing success for his allies and the title of Magnus, or “The Great,” for himself.

Despite his achievements, Pompey chose not to seek election to the Senate and the authority that would bring. Instead, for the next decade, he acted as a military commander outside the formal institutions of the Roman state. During that time, he made himself useful, putting down trouble across the Roman territories.

Spartacus and Crassus

In 73 BC, a group of gladiators led by Spartacus launched a slave revolt. It was an event that shook Rome to its core. These supposedly inferior people put the Roman legions to flight and terrified citizens, especially the wealthy ones.

In 72 BC, another man who had served Sulla in the civil war, Marcus Licinius Crassus, was put in charge of suppressing the slaves. Crassus succeeded. Spartacus was killed in battle and thousands of his adherents crucified.

Pompey, returning too late to fight Spartacus, caught and massacred the last of his fleeing followers. He tried to use this to claim he had been the one to put down the revolt; leading to friction with Crassus.

Then they realized they could do better by working together. Combining for an election campaign, they used Crassus’ vast wealth and Pompey’s popularity to win the powerful positions of consuls.

Pirates

After four years of Roman politics, Pompey returned to action in 67 BC. Provided with 500 warships, 120,000 infantry, and 5,000 cavalry, he went to subdue pirates threatening Roman grain supplies in the eastern Mediterranean.

It was another hugely successful campaign. By showing mercy to the defeated, Pompey extracted information from beaten Pirates, winning a swift and almost bloodless victory.

The East

The following year, Pompey used his public popularity to have himself voted governor of the province fighting Mithridates of Pontus in the East. Usurping the former commander, Lucullus, Pompey finished a war the Romans were already winning. Mithridates committed suicide when his son turned against him.

Using his authority as governor, Pompey roamed the Middle East, carrying out military campaigns and administrative reforms. He intervened in local squabbles as an excuse to expand Roman power, involving himself in a Judean civil war and capturing Jerusalem.

The First Triumvirate

Pompey had fallen out with Crassus again. Even without him, he remained the most powerful man in Rome, without political rival. Many in the Senate feared his unchecked power and radical actions.

Worse was to come for Pompey’s opponents. Another rising star, Julius Caesar, was making them nervous with his popularity. Bringing Pompey and Crassus back together, Caesar formed a secret political alliance between the three men, known as the Triumvirate. Between Crassus’s wealth, Pompey’s military might, Caesar’s political legitimacy, and their popularity, they were unstoppable in their domination of Roman politics.

Political Troubles

Although powerful, the Triumvirate was troubled. Three such ambitious and strong-willed men inevitably came into conflict. Around 58 BC, the political puppets and street thugs acting for Caesar and Pompey in Rome clashed, tearing the two men apart. Crassus brought them back together in 56 BC, helped by the fact that Pompey was married to Caesar’s daughter Julia.

In 54 BC, Julia died giving birth. The following year, Crassus was killed in a campaign at the Battle of Carrhae. Political violence continued to bloody the streets of Rome.

In 52 BC, Pompey married the daughter of Publius Metellus Scipio, an opponent of Caesar. Their alliance was crumbling.

Civil War

Caesar wanted a political office. To gain it, he had to return to Rome without the armies he had gathered on his campaign in Gaul. Fearing that Pompey might not protect him from the violence of the city, Caesar decided to return with his armies.

In 49 BC, Caesar and his army illegally crossed the Rubicon River into Rome’s heartland. A civil war had begun.

In the space of two months, Caesar drove Pompey out of Italy. While Pompey crossed to Greece, Caesar, and his followers put down supporters of Pompey and the Senate in Spain and North Africa. Then Caesar turned his eye to finishing off his rival.

On August 9, 48 BC, the two men clashed for the final time at the Battle of Pharsalus. Pompey, once a great commander, was defeated by the greater tactical skill of his former ally. Defeated, he fled the field.

The End

Pompey sailed to Egypt. With the Empire in turmoil and Caesar on the rise, he had enemies everywhere. On September 28, he was assassinated. His head and body were handed to Caesar. The last triumvirate wept for his fallen opponent.

Pompey was one of Rome’s most successful military commanders. In the end, being one of the most successful was not enough. Not in the face of the most successful.

Sources:

Kate Gilliver, Adrian Goldsworthy and Michael Whitby (2005), Rome at War: Caesar and his Legacy.

Adrian Goldsworthy (2003), In the Name of Rome: The Men Who Won the Roman Empire.