The Romans are rightly remembered as great engineers as well as great soldiers. It was a deadly combination in a siege.

As their empire expanded across Europe and the Mediterranean, many enemies of Rome chose to hide behind the walls of towns and fortresses rather than face the legions in open battle. This, however, proved to be no safer for them, as shown during these four great Roman sieges.

Veii, 405-396 BC

The siege of Veii was one of Rome’s early conquests. Veii was an Etruscan city and close neighbor of Rome.The two competed for influence in the region, and they fought inconclusively for several years.

Then came Marcus Furius Camillus, dictator of Rome. At the time, the word dictator referred to a political and military leader given temporary emergency powers, rather than the iron-fisted leader it now represents. Camillus set about ending the war with Veii.

Laying siege to the city, Camillus set up a blockade camp to cut off Veii. This included several smaller fortified positions and one main camp. When a relief force came to rescue the city in 402 BC, the Romans were driven back to their main camp but clung on there, eventually retaking the rest of the siege works.

After years of siege, Camillus set upon a mine as the way to defeat Veii. Crews worked in six-hour shifts day and night to dig a tunnel beneath the city walls. When it was completed, Roman soldiers poured into the center of Veii. The city fell, and Rome had one less rival in the region.

Carthage, 149-146 BC

For over a century, the Carthaginian Empire was Rome’s greatest rival in the Mediterranean. Then, around 140BC, the Carthaginians were on the ropes. Laying siege to Carthage itself, the Romans set out to tear the heart from the opposing empire.

The siege of Carthage began inauspiciously. The Roman commanders Censorinus and Manilius misjudged where to build their camps, leading to sickness and death among their men. Despite building a road across a lagoon for two vast battering rams, Censorinus was unable to penetrate Carthage’s walls.

Then the rising star Scipio Aemilianus came to take over the siege. He fixed problems of discipline, morale, and supply. He moved the siege works closer to the walls of Carthage, applying pressure to the city and cutting it off from support by land. He had his engineers build a barrier of huge stones across the mouth of the harbor, so blockade runners could not bring supplies to the city.

Bit by bit, Carthage was worn down. An outer fortification was abandoned. Suburbs fell. Finally, after launching attacks around the harbor and building high ramps to the tops of the walls, the Romans broke into the city.

The starving defenders fought tooth and nail in a bitter house-to-house struggle that stained the streets red. Ultimately, they were no match for Rome.

Carthage fell. Its buildings were destroyed, and its citizens carried away. Scipio was determined not to leave a center for future resistance.

Alesia, 52 BC

Julius Caesar’s greatest achievement, the conquest of Gaul, was completed through a successful siege.

In 52 BC, Gallic forces had retreated to the fortified hilltop town of Alesia. The Gallic leader Vercingetorix was gathering forces elsewhere in the region and presented the greatest threat to Caesar.

However, Alesia could not be left unattended while the Romans chased the Gallic chief. Caesar had gambled his political career on conquering Gaul and so his future hung in the balance.

The siege works at Alesia have become the gold standard for how we imagine a Roman siege. They surrounded the town by circumvallation – a complete circuit of both inward and outward facing works that could hold off attacks from inside Alesia and also relief forces from outside.

The strongest sections were incredible works of engineering. The Gauls had first to cross two ditches. Then a field of stimuli – short buried stakes with protruding iron spikes. Followed then by a field of cippi – branches fastened together and set in a trench, their sharpened ends projecting out of the ground like barbed wire. Finally, came a third ditch and behind it, a rampart topped with a palisade and towers. Meanwhile, missiles poured down upon the attackers.

Vercingetorix gathered his forces and tried to relieve Alesia, but was unable to overcome the Roman defenses. The inhabitants of the town were starving and would soon have to surrender. Without them, he stood no chance. He surrendered to Caesar, earning the Roman general a triumph back home and the Gallic chieftain six years in captivity followed by public execution.

Masada, 73-74 AD

In 66 AD, a Jewish revolt broke out against the Roman Empire. Although the central rebellion was crushed at Jerusalem, around 960 rebels led by Eleazer Ben Yair retreated to the hilltop fortification of Masada.

Half fortress, half palace, Masada had been built by Herod the Great as a luxurious refuge for times of crisis. Sitting on top of a rocky, steep-sided hill, it was reached only by a single winding path that could be defended by a handful of men. There were deep cisterns full of rainwater, storerooms filled with supplies, and even space to grow crops. It could not be starved out, nor easily attacked.

Led by Flavius Silva, the governor of Judea, the Roman besiegers outnumbered the defenders five to one. Also, they were all military men, while many inside were civilians, children, and the elderly.

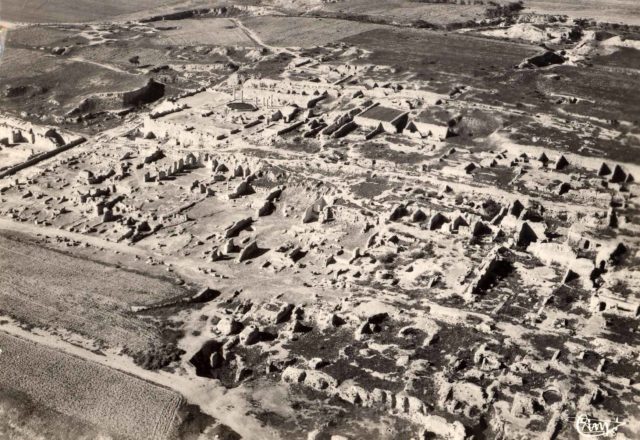

The Romans built a line of circumvallation around Masada, cutting it off from the outside world. It included six small forts, several towers, and two large military camps. Emplacements allowed artillery to fire at the walls and at any rebels who ventured forth.

Setting out from these works, Roman engineers built a long ramp of dirt and rubble on an existing spur of rock. Going from the desert floor to the top of the hill, it created a better route up for the attackers than the existing path. They also built a siege tower with a battering ram which could be hauled up this slope.

However, when they broke through the walls, the Romans did not find a fierce fight. Instead, they found a thousand dead bodies. Rather than let themselves be taken, the rebels had killed their families and then committed suicide.

Some of Rome’s greatest siege works won not through their implementation but through the intimidation their presence caused.

Sources:

- Gwyn Davies (2006), Roman Siege Works.

- Adrian Goldsworthy (2003), The Complete Roman Army.

- Adrian Goldsworthy (2003), In the Name of Rome: The Men Who Won the Roman Empire.