“I have seen my people prepare for battle many times,” she said, “and this I know: that the Sioux that morning had no thought of fighting.”

American history is full of iconic battles. Most of the more famous ones were of course victories. Scattered within the names of victories such as Yorktown, Gettysburg, Normandy, and Iwo Jima are others: Pearl Harbor, Bataan, Bunker Hill – all defeats, but which have a luster to them for the heroism involved.

One name, however, signifies total defeat and humiliation, unless you are Native American, and that’s Little Big Horn, which took place in late June 1876.

Today the battle is somewhat of a footnote – a monument to one man’s hubris – but at the time, Little Big Horn came as almost as big a shock as Pearl Harbor in 1941, or 9/11. People were stunned.

They couldn’t believe the US Army had been defeated so soundly, especially when many people believed the natives were on the verge of total defeat. Americans couldn’t believe a national hero such as Custer could have been beaten, and so badly. And of course, they wanted revenge – which they got, and which was part of the national tragedy that were the Indian Wars.

Little Big Horn became a by-word for defeat. Actually, the battle’s name wasn’t uttered much, but it did take on a more heroic one: “Custer’s Last Stand,” and those three words became part of the American lexicon.

Let’s examine 10 of the more common myths surrounding Little Big Horn, or “The Battle of the Greasy Grass” as it was known to the Sioux, Cheyenne and Arapaho warriors that took part in it.

Let’s kill a couple of myths up front: Custer did not have long hair at the time of the battle, many people survived (just not from the US Army), and the officers of the 7th Cavalry did not lead a charge with their sabers, which they left behind. Now let’s get to some of the other misconceptions about the battle…

Actually, a number of soldiers survived

Custer led a force of 31 officers, 586 soldiers, 33 Native scouts, and 20 civilian employees. When the battle ended in the evening of June 26, 1876, 262 men were dead on the field, 68 were wounded, and six died of their wounds some time afterward. The units of Custer’s battalion, companies C, E, F, and I, were wiped out.

However, most of the men of the seven other companies present, under the command of Major Marcus Reno and Captain Frederick Benteen, survived the battle.

Custer ignored his Native scouts

A common idea is that Custer, a decorated Civil War hero and perhaps the best-known officer in the West, ignored his Native scouts and totally dismissed their value. This is not the case. He did listen, but they were about as wrong as anyone else.

On the evening of the 25th, Custer was told that there was a large Native village about 15 miles away. Custer believed these men but wanted to wait until the next morning to attack, marching quietly through the night to surprise the Sioux at dawn.

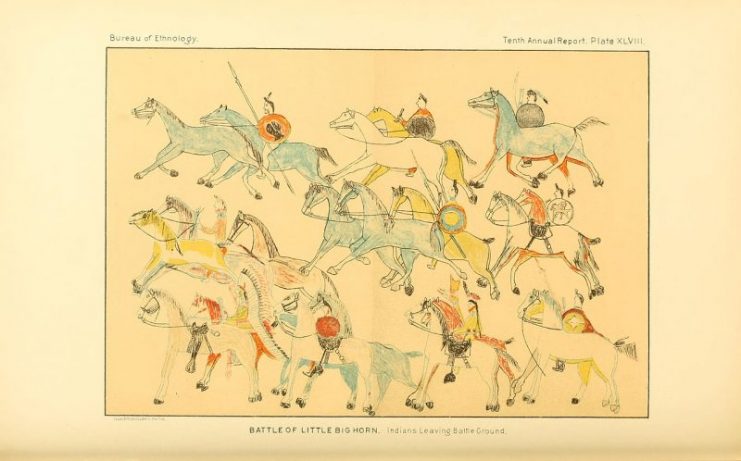

Date between 1880 and 1884

He told one of his scouts, Half Yellow Face, “I want to wait until it is dark, and then we will march.” This scout, a Crow, argued that the Sioux “have seen the smoke of our camp” and pushed for an attack.

Another Crow scout, with the unenviable name of White Man Runs Him, spoke up and told Custer that the enemy had already seen the soldiers. An Arikara scout named Red Star agreed with the Crows and told Custer his should attack and “capture the horses of the Dakotas.” Like the Lakota, these were a branch of the Sioux.

As Custer pondered, some of his men told him about some Natives they had seen rifling through a pack train at the rear of his column. With all of this information, Custer ordered his attack. He did not ignore his scouts.

The Native village was huge

In movies and documentaries, the mobile village is shown to be massive. Many times, infantrymen are shown coming up over a rise to see a gigantic village in the valley below, and they know their “number is up.”

This was not the case. The village was big – estimates from survivors on both sides, combined with the geography of the area and other factors, put the village at about 1½ miles long, along the river that gave the battle its name. From all accounts, there were at least a dozen other Native settlements throughout the West that were bigger.

The Natives under Sitting Bull set up an ambush

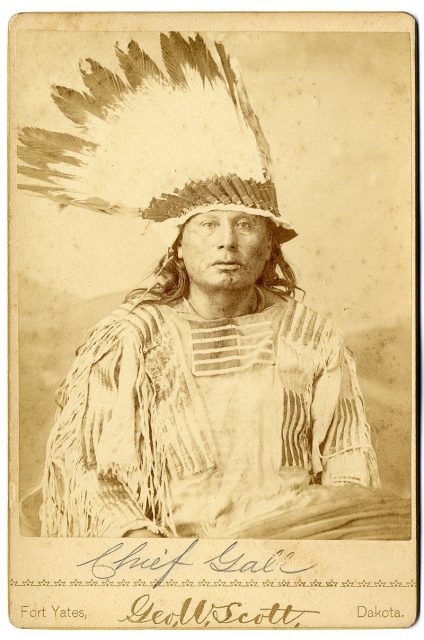

Aside from Custer, the most famous personality of the battle was the Lakota chief, Sitting Bull, who became one of those rare things in war – a respected enemy.

One of the native women, Pretty White Buffalo, later gave an account of events. “I have seen my people prepare for battle many times,” she said, “and this I know: that the Sioux that morning had no thought of fighting.”

Another, Antelope Woman, later known by her Americanized name of Kate Bighead, recounted that there were scores of naked men, women and, children in the river, bathing or playing. Others were fishing downstream. Everyone was having a good time.

In fact, far from planning an ambush, the Sioux and their allies were unaware of Custer’s approach, though they believed a force of soldiers to be in the area. Sitting Bull himself was caught up in the initial confusion of Custer’s appearance.

His wife Four Robes grabbed their twins and sprinted for the hills when soldiers were first reported. In her panic, she left one child behind and had to go back to retrieve it. Later they called the child “Abandoned One.” Custer had actually surprised the Sioux, not the other way around.

Custer’s tactics were poor

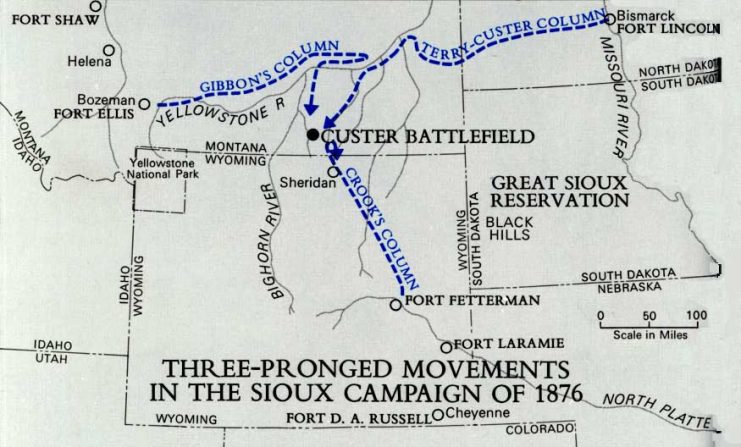

Though many a tactical thinker throughout history has written that dividing your force in the face of the enemy is a mistake, many others have used the opposite tactic to surprise, flank, and trap the enemy. The most famous instance of this in American history is Lee and Jackson’s attack on Union forces at Chancellorsville. At Little Big Horn, Custer tried a similar approach.

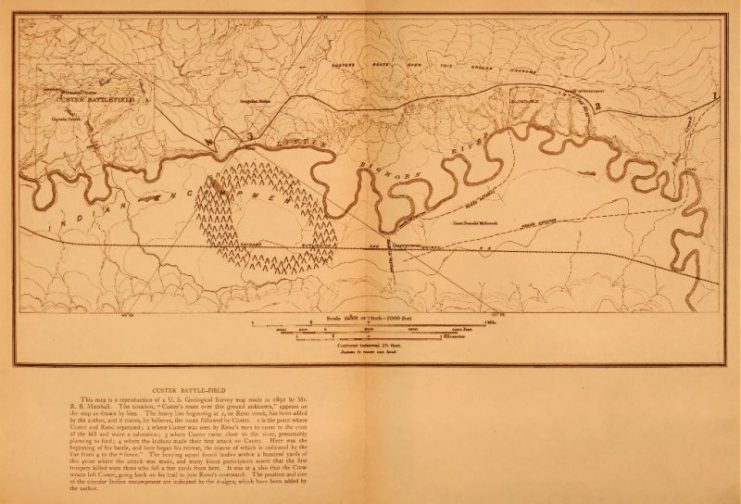

Custer’s subordinate, Major Reno, attacked the southern end of the village, while Custer circled to the north along the bluffs of the river. Sometimes, however, planning doesn’t translate into victory. Paraphrasing boxer Mike Tyson “Everyone has a plan, then they get punched in the mouth.”

Reno got punched in the mouth: the Sioux got things together after the initial surprise and pushed Reno back across the river, further separating him from Custer.

At that point the famous warrior Crazy Horse rode up to where another warrior, Short Bull, was helping drive Reno across the river. Short Bull told him: “Too late! You’ve missed the fight!” Crazy Horse replied: “Sorry to miss the fight, but there’s a good fight coming over the hill.”

Short Bull looked north to see the “Blue Coats” under Custer to the north. Crazy Horse said, “That’s where the big fight is going to be. We won’t miss that one!”

Custer died at the river

In movies, books and newspaper accounts of the time, Custer is reported to have been shot down in the middle of Little Big Horn as he was trying to retreat eastward across the river.

But by the time of Custer’s reported death in the river, Cheyenne warriors were already there and had been for some time. Custer would not have retreated into a force of waiting Natives. Troops and warriors shot at each other from opposite sides, so Custer knew retreat east wasn’t an option.

A warrior named Standing Bear reported that there was “no fighting on the creek.” Another, Bobtail Horse, stated like many others that the Natives and Custer’s men were both fighting on the east side of the water, and that no troops were near the water.

Among others, a man named White Cow Bull (who also falsely claimed to have stopped an entire cavalry charge in the river) later said that he and Bobtail Horse shot down a buckskin-clad soldier, which was Custer. Bobtail Horse never claimed that, and even doubted that White Cow Bull was there.

Other Natives, both male and female, told stories of Custer being too drunk to fight, or that they had “heard from someone, who heard from someone” that Custer had been shot in the chest in the river.

Crazy Horse’s Charge

One of the iconic images of the battle is that the famous warrior Crazy Horse gathered running braves about him and charged into the battle, overwhelming Custer and turning the tide of the battle. A number of authors have repeated this claim through the years.

Lately, historians, most notably Gregory Michno (whose research into Native accounts, published in his book Lakota Noon: The Indian Narrative of Custer’s Defeat and The Mystery of E Troop: Custer’s Gray Horse Company at the Little Bighorn, was the basis of the quotes in this article) have developed a new theory.

Though he arrived late in the battle against Reno, Crazy Horse and some warriors did engage Reno’s troops. This is near a spot called Calhoun’s Hill, and many witnesses report his being there at the same time that historians have him a mile or so away leading a charge against Custer.

Before he was killed in US captivity just over a year later, during a moment with interviewers Crazy Horse, through his aide Horned Horse, told the story of the battle as it was reported above. The only time that Crazy Horse led any kind of rapid charge against soldiers was towards the end of the battle, as the US soldiers attempted to flee.

The idea of Crazy Horse’s charge comes from a variety of sources. Some were from Natives trying to impress their people with Crazy Horse’s bravery, though they didn’t need to since he was already famous by the time of Little Big Horn. Some were from white soldiers who reported seeing him on horseback, along with other accounts clouded by the fog of war.

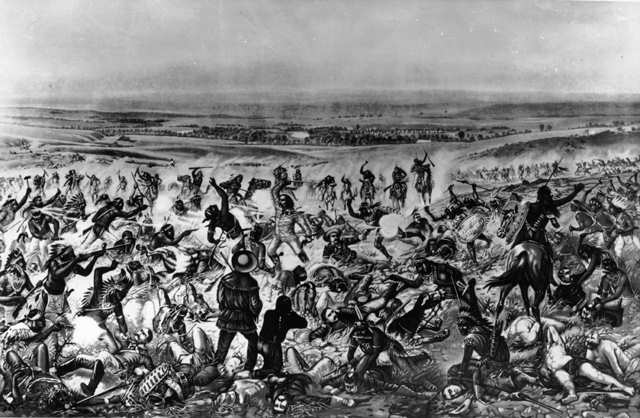

The “Last Stand”

Some people believe that Custer’s men were simply cornered and were essentially overwhelmed. Others have the bulk of his troops in a circle, fighting an organized final stand, like in the famous 1941 movie They Died With Their Boots On.

The truth is somewhere in between. We know that Custer’s men didn’t just roll over – they fought tooth and nail and weren’t overwhelmed easily.

The truth is that there was an assortment of final stands. Natives rushing to the final part of the battle saw evidence of groups of soldiers who had died in place, fighting warriors on all sides. The final one of these stands has been labeled “Custer’s Last Stand.” It actually was the warriors that gave it this label and it stuck.

All the warriors later interviewed had no problem admitting that the soldiers fought bravely and well. Iron Hawk, who was there, said, “The Indians pressed and crowded right in around them on Custer Hill, but the soldiers were not yet ready to die. They stood here a long time.”

The Deep Ravine

Visitors touring the Little Big Horn battlefield today come to a place called “The Deep Ravine” where a historical marker tells them that 28 soldiers were killed there, as Natives shot at them from the sides and top of the ravine.

However, many eyewitnesses said that there were only a few men there, and only a few bodies were found there when the battle ended. Over the years, bones and artifacts from the battle have been found at the battlefield, but one place that they really haven’t turned up is at the Deep Ravine.

Read another story from us: Are We Erasing History?

Historians claiming that people died at certain spots at the battle base their theories on the fact that bones and other objects, like shell casings, have been found in those places. The Deep Ravine has not turned up this evidence. Yet the myth of soldiers being helplessly gunned down in the earth has lived on since the time of the battle, when newspapermen wanted to make clear who the “savages” were.