The Civil War mobilized American resources on a scale only matched in WWII. It brought unparalleled destruction to many people. How did an initially restrained conflict between friends, relatives, and neighbors become so devastating?

The Nature of Total War

The phrase “total war” is a difficult one. Carl von Clausewitz described it as “absolute war” or a war without limits, where no distinctions are drawn between civilians and soldiers. Everyone is a target.

In WWII entire cities and their populations were destroyed. The American Civil War never reached that level, but civilian society was deliberately and heavily hit.

A Limited Start

The war began with restraint. The Confederate President Jefferson Davis said, “all we ask is to be let alone.”

Union President Abraham Lincoln looked upon it as putting down a domestic insurrection. A limited force was to be used to reunite the ruptured nations.

Frémont in Missouri

Many in the Union sought a more vigorous approach. It was a chance to eradicate slavery. They believed strong measures were needed to achieve it. However, to some, slaves were regarded as property by their owners and in the laws of the slave states. To free them was to violate their assets.

In 1861 Missouri was the testing ground. It had been caught up in the violence between slave owners and abolitionists before the war and had become brutalized by guerrilla conflict and banditry. John C. Frémont, the Union Army’s commander in the West, placed the state under martial law. Confederate guerrillas were executed, their supporters property seized, and their slaves freed.

Lincoln, looking to avoid reprisals, relieved Frémont of his command but a precedent had been set.

1862

1862 was a tipping point. Over the previous winter and spring, the Union had repeated successes. Then came Confederate counter-offensives. Jackson and Lee in Virginia; Bragg and Smith in Tennessee. They threw back the Union forces and marched north.

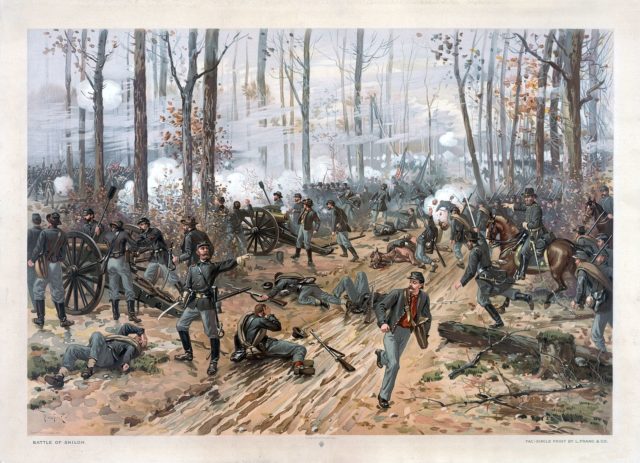

At Shiloh, the Confederates almost beat General Grant. He became convinced that only complete pursuit of war could defeat them.

Emancipation and Total War

Meanwhile, the Union government had given up on protecting the rights of slave owners. They realized they had to face the controversial issue of emancipation – but only in the rebelling Southern states.

In July 1862, Congress declared that any Confederate-owned slaves joining the Union would be emancipated. In September, Lincoln announced the Emancipation Proclamation declaring that if the Southern states did not cease their fight, then all slaves in the Confederacy would be free with effect from January 1, 1863.

To the Confederates, it was an attack on their property. Also, in placing the rights of slaves above those of owners, they believed the Union was precipitating a slave rebellion. Total war was one step closer.

East Moves West

From early in the war, the fighting in the west had been less restrained. The violence and lawlessness pushed Union generals to retaliate against civilians and their property. Far from Washington, those commanders got away with more.

In the summer of 1862, two of them, Pope and Halleck, were brought east. There they extended the scope of military activities. Among other things, Halleck wrote to Grant telling him to seize the property of Confederate supporters and to “handle that class without gloves.”

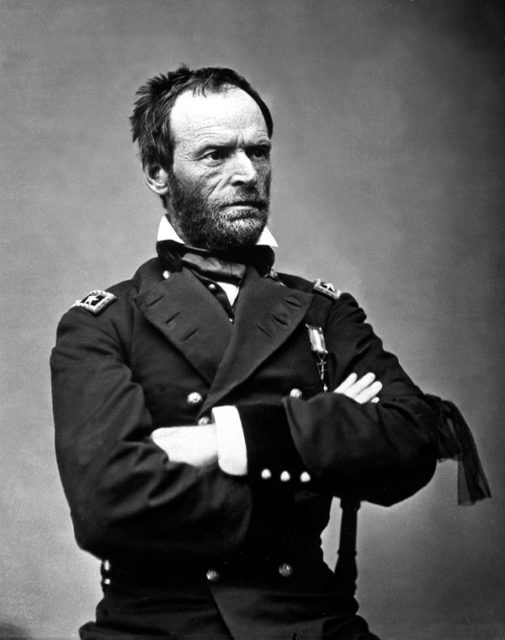

Sherman and the Heights of Total War

Of the western-influenced Union Generals, Sherman was the harshest in inflicting total war. At the start of the conflict, he had seen brutal fighting by guerrillas in Missouri. He regarded the civilians there as dangerous as the enemy military.

Sherman was not merciless, but he was harsh. Houses suspected of sheltering snipers and guerrillas were burned down. The civilian population of Atlanta was driven out. He promised to “make Georgia howl.”

For Sherman, the war was as much about punishing the civilian support base as hitting the military.

Grant and the Vindication of Total War

Grant, the Union’s most celebrated commander, also made his name in the West. His experiences there shaped his approach to the war.

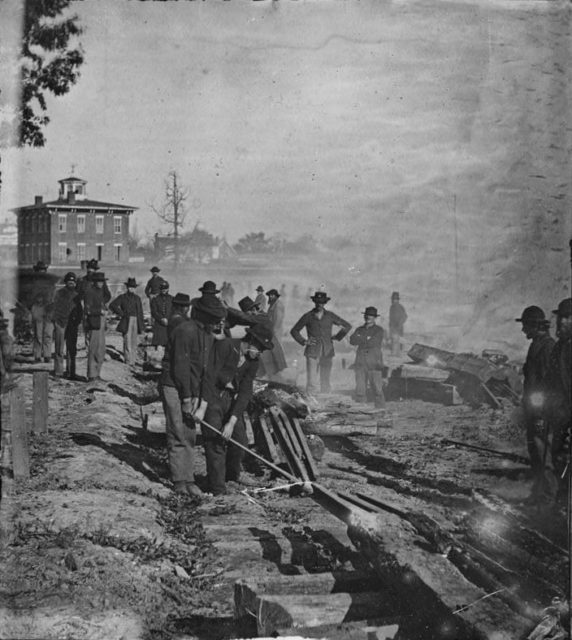

As would recur during WWII, Grant attempted to destroy the economics and morale of the enemy. By tearing up railroads, he deprived their forces of supplies and communications. As they marched through the Confederacy, Grant’s army took their food from the surrounding farmland. What they could not take, they burned. He aimed to demoralize the civilian population, reducing their willingness to support the war.

Bark Over Bite?

For all the destruction, both sides talked tougher than they walked.

People on both sides called for terrible destruction. A Savannah newspaper said, “Let Yankee cities burn and their fields be laid waste.” A Nashville woman prayed to God to let them exterminate the people of the Union. Sherman talked about slaying millions and repopulating Georgia.

There was restraint. Most civilians were protected. Destruction of property depended upon the commander and the circumstances. Even Sherman did not lay everything in sight to waste.

The Staggering Cost

There was more bark than bite, but the bite was still terrible. An estimated two-thirds of the wealth of the Confederacy was destroyed. It was either used in the fighting, ruined by the Union or lost as the monetary value placed on slaves.

A quarter of the white men of military age in the Confederacy were killed, and nearly 4% of the south’s total population died in the war.

It was not Clausewitz’s absolute war but it was a war in which the boundary of destruction was continually expanding.

In the south at least, it earned the title of “total war.”

Source:

John Keegan (1987), The Mask of Command

James M. McPherson (1996), Drawn With the Sword: Reflections on the American Civil War