When not in combat, a soldier during the American Civil War, whether Union or Rebel, often found himself idle for great stretches of time. Writing home or in personal journals was a common pastime for soldiers, then and now.

One such journal, belonging to a William C. Johnson, Private, Company F, 89th Ohio Volunteer Infantry, First Brigade, Third Division, XIV Army Corps, carried two trends throughout his writing. These trends are reflective of other soldier’s remarks during the war, and give the devastating conflict a distinctly human, personal touch.

The first trend was a constant eye on the weather, out of boredom or, perhaps, a desire for dry boots. The second was the Union Army’s lust for revenge against the state that started it all, South Carolina.

But more than just weather and war, the journal helped establish a culmination of revenge on the first state to secede, the impotence of the Rebel military, and the despair of the Rebel civilian population. This congealing of trends and issues of the war coalesced at the Battle of Bentonville, a small clash in North Carolina between General William Tecumseh Sherman and General Joseph Eggleston Johnston.

The very first dated entry in Pvt. Johnson’s journal began “cold, cloudy, dreary, foggy and rainy….” He would write often about the weather, his eyes on the sky as the army marched across the rebelling south. With warfare decided by the seasons, and the need to keep their powder dry, the Private’s obsession with the weather is understandable; good weather meant an easier march, non-spoiled food, and functioning weapons to protect against ambush.

Most of the journal entries began with a brief description of the weather, ranging from “colder, but clear” to “cool and cloudy.” Near the middle of the journal, when Rebel resistance to the march and “foraging” from local towns increased in intensity, the weather reports tapered off into a short mention within a longer entry, or are not existent at all.

For a private marching through vast tracks of land, simple boredom may be the most likely reason for weather descriptions; if something more interesting occurred, he would write about it.

For a Union Army soldier, another popular pastime besides writing in their journal was foraging for something to eat besides hardtack and beans.

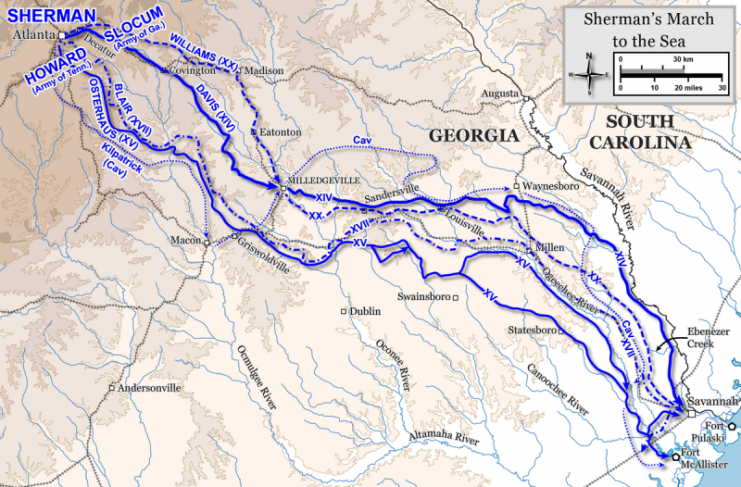

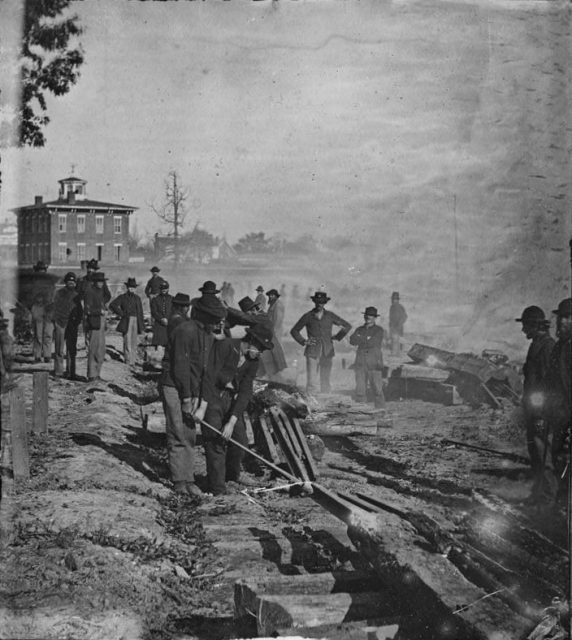

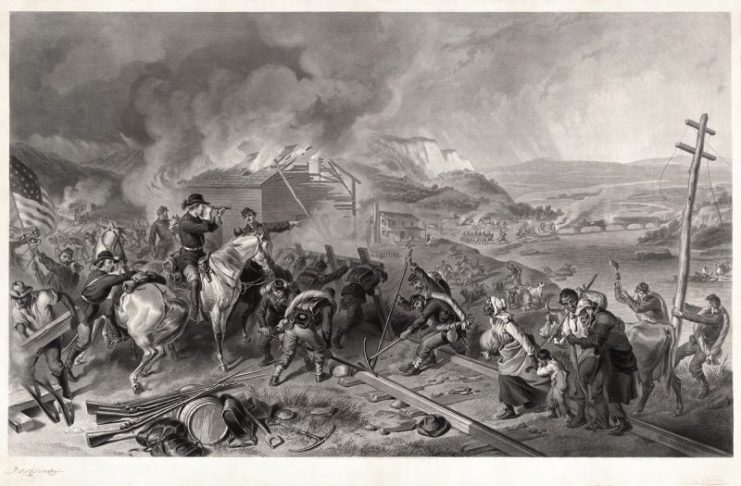

As General Sherman’s army carved a swath of Total War through what remained of the Confederacy, Union forces started grabbing anything not nailed down, particularly upon reaching South Carolina. Pvt. Johnson brought this up in his journal, writing on February 5th (a Sunday), “Weather clear and pleasant… Crossed the Savannah River on the Pontoon Bridge and for the first time in my life set foot on the sacred soil of South Carolina about noon.

As we leave the bridge one of the boys of Company A, near the head of the regiment, stepped out from the ranks and turning around yelled in a lusty voice, “Boys, this is old South Carolina, lets give her hell,” to which there was many favorable response.”

Once the Union forces entered South Carolina, Pvt. Johnson’s journal entries become more detailed, including records of loot acquired from the local populace, and Rebel Calvary skirmishes against General Sherman’s army and the attached cavalry.

The first entry mentioning forage occurred on February 11, where the army obtained “bacon, ham, fresh meat, sweet potatoes, chickens, turkeys, meal flour, molasses, etc.” The same entry mentions early Rebel resistance. “Rebels are in force at Aiken, our cavalry entertaining them with a few little skirmishes occasionally, just to let them know we are around.”

In contrast to the Union smorgasbord of fresh foods obtained from the populace, and the cavalier attitude the soldiers had of the Rebel soldiers, the southerners watched Sherman’s rampage in an air of forlorn gloom.

One citizen, writing from the soon doomed city of Columbia, South Carolina, noted that she “felt utterly despairing.” Despite the rampant destruction and acquisition of personal property, Pvt. Johnson makes no notes of altercations between soldiers and civilians in his journal.

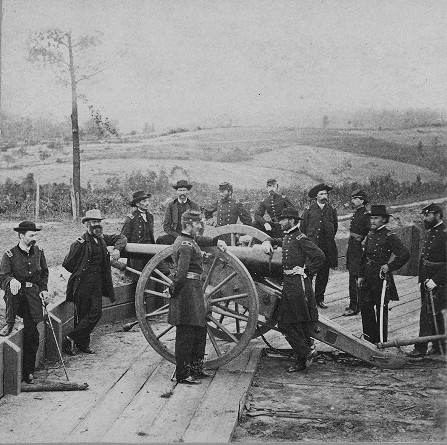

The largest battle noted in Pvt. Johnson’s journal was the Battle of Bentonville, a relatively minor battle in South Carolina where sixty thousand Union soldiers faced off against less than twenty-two thousand Rebels.

Meant to halt Sherman’s advance, the battle was the last between General Sherman and General Joseph E. Johnston, commanding the ragged remains of the Army of Tennessee, who surrendered to Sherman a month later.

The day before the battle itself, Pvt. Johnson noted heavy preliminary cannon fire. The next day, with the Rebels defending as best they could against the Union onslaught, “We came up to the balance of our Corps and found them confronted by a large Rebel force under General Johnston, and soon learned that there had been heavy fighting on yesterday…”

Pvt. Johnson’s unit found itself arriving ahead of the bulk of General Sherman’s Army, and his commander attempted to push through the Rebel defenders without waiting for reinforcements. After the initial previously mentioned Rebel artillery assault, Pvt. Johnson’s Brigade found itself outnumbered by the defenders. Fortunately, nearby reinforcements saved the Brigade for the time being, but only after “our troops had been driven from several hastily thrown up earthworks.”

The Rebels charged this final defense “some seven different times,” but the Union soldiers held the line long enough for the rest of General Sherman’s Army to arrive. Heavily outnumbered, and with General Johnston’s rear threatened by the XV and XVII Corps, the remains of the Army of Tennessee retreated, ending the Battle of Bentonville.

For the victorious Union soldiers, the beleaguered Rebels, and the civilians of the so-called Confederate States of America, the Battle of Bentonville was the signal that the Civil War neared its end. As for Pvt. Johnson, he survived the war, earning a promotion to Sergeant and reassignment to a unit of Colored Troops. He died in 1917 from illness, a common end for a veteran of one of America’s deadliest conflicts.

Cited Sources:

Company F Roster, 89th Ohio Volunteer Infantry.

Dan L. Morrill, The Civil War in the Carolinas, Charleston, S.C., (Nautical & Aviation Pub. Co, 2002).

Mary Boykin Chestnut, Ben Ames Williams, ed., A Diary in Dixie, (Harvard University Press 1980).

William C. Johnson, “Through the Carolinas to Goldsboro, NC,” Library of Congress Archives,

Washington, D.C.