Most people know of the kamikaze pilots of WWII who deliberately piloted their planes into Allied ships during the latter stages of the war. Many people also know that the name “kamikaze” is derived from Japanese Shinto belief and means “divine wind.”

WWII documentaries will tell you that the name was adopted because a “divine wind” had twice protected Japan from invasion by the Mongols in the 13th century. The impression is that a huge Mongol fleet twice appeared off the coast of southern Japan and each time, a typhoon occurred destroying most of the fleet.

That’s not the whole story. The reality is that, on both occasions, the Mongols arrived off the shores of Japan and landed sizable forces. They fought pitched battles with the Japanese, some of which they won and some of which they lost. It was then that they were hit by storms which destroyed much of their fleet, making further efforts impossible.

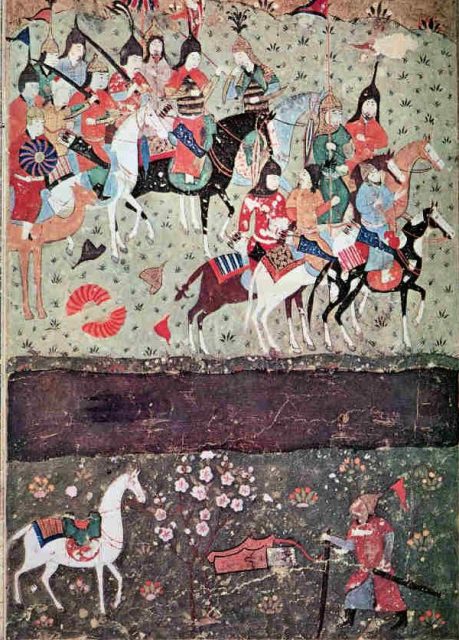

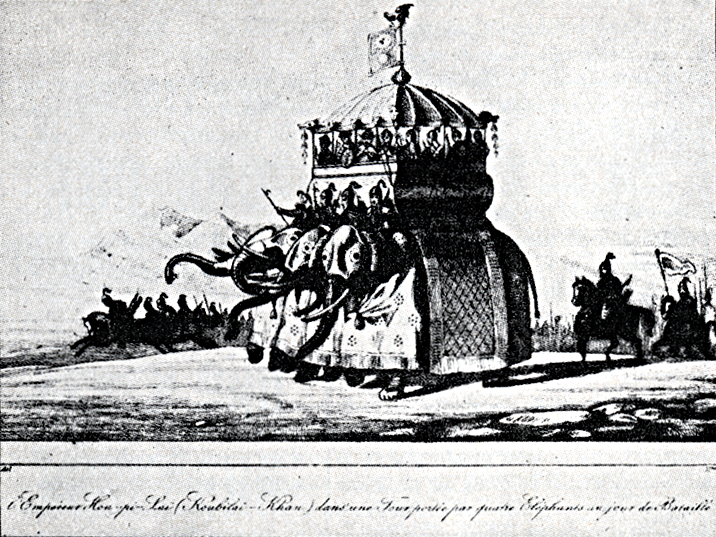

Kublai Khan, the grandson of the Mongol conqueror Genghis, rose to power after a civil war within the family ranks. Though supposedly the “Great Khan,” ruling over all Mongol conquests from China to the gates of Europe, Kublai’s real territory was “only” Mongolia and China.

Despite controlling less land than his illustrious grandfather, Kublai presided over a vast, rich, and immensely powerful empire. As a young man, he had helped subdue territories in the Middle East and then turned to China. He was recognized as a skilled warlord, especially in terms of logistics.

In 1260, Kublai invaded Korea and forced the Korean king both to pay tribute and contribute troops to the Mongol army. Only a short distance across the Korea Strait is the southernmost Japanese island, Kyushu. Kublai soon had his eyes on making Japan a tributary as well.

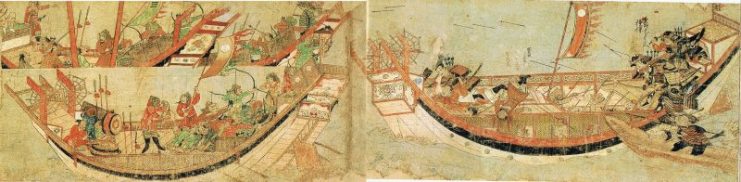

But Japan presented a much more difficult problem than Korea, the obvious reason being that it is an island nation. The Mongols, famous for their cavalry and tactics on land, had very little experience at sea. Even their Chinese and Korean admirals and generals, more familiar with the sea than the land-locked Mongols, had no experience of mounting a large-scale seaborne invasion.

On the other side of the Korea Strait in the period 1266-1281 were the Japanese samurai, ostensibly ruled by the shogunate (military dictatorship) based in the city of Kamakura.

In the late 1200s, the shogunate was a complicated structure. For the first century of the Kamakura Shogunate, power was “shared” between two great families: the Minamoto and the Fujiwara. After a complicated series of political maneuvers and battles, a new title of “Shikken” (a type of regent ruling in the name of the emperor) was given to the ancient Hojo clan, who ostensibly had authority over all of the country.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w2y9wDxEJzw

That power was limited, and in reality, local warlords both large and small ruled the country, generally allied with one of the two other powerful families. Those warlords and families controlled their own private armies.

What made things even more confusing was that all along the coasts of southern Japan, pirates raided both one another and shipping in the Pacific along the coasts of Korea and China. This gave Kublai Khan the excuse he needed to demand that Japan yield to his power and become a tributary state, as the Koreans were.

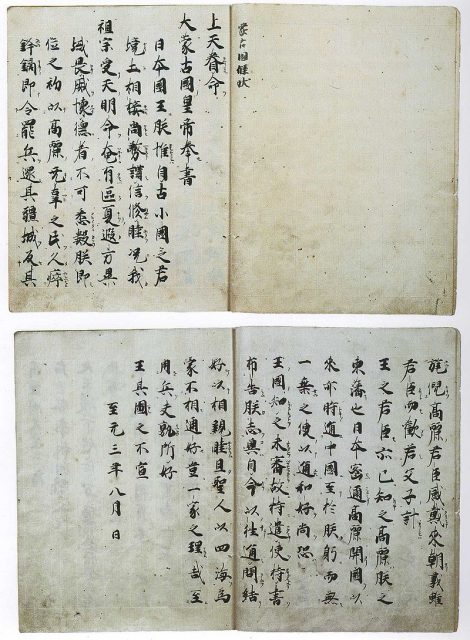

In 1266, Kublai sent a letter to the Japanese via trusted diplomats. The note politely listed grievances Kublai had with Japan, not least of which was that they had never recognized his over-lordship of China and Korea. The last line of the note politely but ominously threatened war: “Nobody would wish to resort to arms.”

The Japanese did not reply and the diplomats returned to the Khan empty-handed. Two years later, more Mongol diplomats arrived and again went home without an answer.

Each time, while the diplomats waited offshore (they were not permitted to land), the Japanese debated what to do. After the second note arrived, the Shikken and the leaders of the most powerful families were in rare agreement: preparations to defend Japan had to be undertaken.

For the next six years, the Japanese prepared their southwestern coasts for invasion.

The Khan was preparing as well. No answer to his letter was more disrespectful than an outright “no.” It implied he was not a person worth replying to. Kublai immediately ordered the building of a great fleet in Korea and summoned armies from all over his empire.

In 1274, the Mongol army (including not just Mongols, but Koreans and some Chinese) boarded hundreds of ships and crossed the Korea Strait. For centuries, historians both West and East claimed Kublai’s fleet numbered in the thousands with the men aboard reaching over 100,000. This would have rivaled the D-Day invasions 600 years later.

Today, both Chinese and Western historians number the fleet in the hundreds with the army aboard reaching somewhere between 25,000 and 40,000 men. Though not the monstrous army many believed it to be for so long, Kublai’s force was still huge for the time, and many of its men and leaders were battle-hardened.

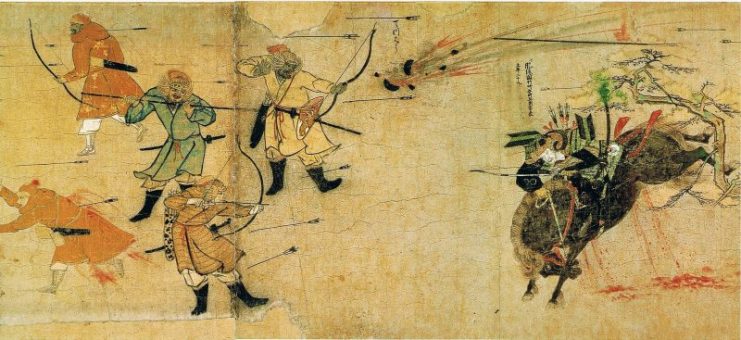

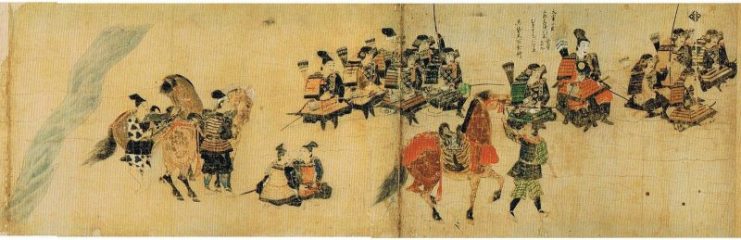

The Mongol-led force landed first on the small island of Tsushima, hoping to use it as a staging area for the main effort. The 200 samurai unsurprisingly all fought to the death, hopelessly overwhelmed. Here, a significant difference in the tactics of each force was made apparent.

The Mongols and their allies were used to fighting over vast distances, mostly on flat, featureless plains or deserts. This called for large numbers of troops, cavalry, and skill at maneuvers.

The Mongol armies fought as a group, using group tactics and eschewed the individual one-on-one fighting that the Japanese samurai both prided himself on and considered honorable.

In many of the large Japanese battles (especially of the early samurai era), leading warriors fought man-on-man. Helping your comrade by stabbing his opponent in the back was considered both cowardly and disrespectful – did you not believe your comrade capable of beating his foe?

In the initial stages of the invasion, the massed Mongol tactics and superiority of numbers overwhelmed and confused the Japanese, who were defeated in the first three battles of the war.

Each of these battles took place on islands off the coast. They were supported by ships carrying catapults which shot flaming and exploding barrels of gunpowder, which the Japanese had never seen before in battle.

After invading the three islands, the Mongols landed on Kyushu, in Hakata Bay near present-day Fukuoka. There they were met by larger Japanese armies who had, to some extent, adapted to Mongol battle tactics. Two battles were fought, both of which resulted in Japanese victories.

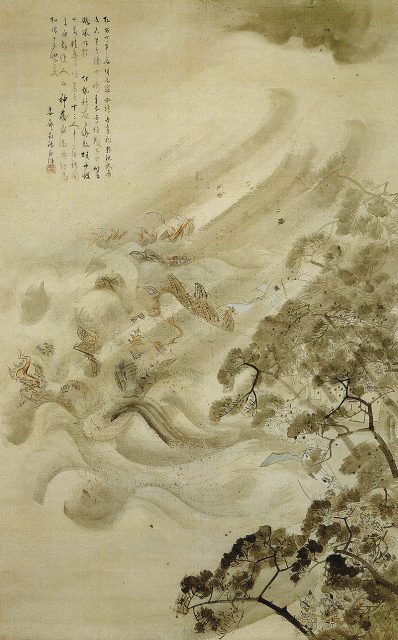

Deciding to head for home to regroup and resupply, the Mongol forces retreated to their fleet. As they set sail, a massive storm blew in, sinking many ships and men and damaging those left afloat.

For the next five years, Kublai finished vanquishing the previous ruling Chinese dynasty, the Sung, who had held onto lands in the south of the country. Finally defeating them, the Khan returned his attention to Japan.

Once again, he sent diplomats with a note demanding that the Japanese recognize his over-lordship. This time, the Japanese, who had spent the last few years building defenses to repel another invasion, were not confused. They sent back an answer to Kublai: the heads of the diplomats.

In mid-summer 1281, Kublai sent an even larger invasion force. They were defeated by the Japanese at each of the five major battles of the campaign.

Making matters worse, the Japanese launched commando-style raids on the Mongol fleet. At times, samurai swam out and stole aboard an outlying Mongol vessel at night, decapitating the crew before swimming home.

Read another story from us: Six Years & a Pile of Bones- The Mongols Take a Chinese City

The Mongols and their allies were forced to live through the hot summer aboard their ships, hoping that the next time they attacked they would be successful. On the night of August 15, 1281, another storm, this time a huge typhoon, hit the coast of Japan. Most of the fleet was destroyed. Those who didn’t drown were slaughtered by the Japanese.

The Divine Wind had protected Japan again. No force would attempt to invade the country again until 1945.