On March 26, 1944, the submarine USS Tullibee made radar contact with a Japanese convoy carrying troops and prepared to attack it despite harsh weather conditions. It was the last time anyone would hear from the submarine, which along with the entire crew seemed to have just disappeared. It was believed to have been sunk by a Japanese destroyer during the attack on the convoy, or perhaps by another submarine.

That was the assumption until after the war ended. Only after Japan surrendered and American prisoners of war were released, did the only survivor from the Tullibee appear to tell the story of the lost submarine. It had not been hit by an enemy vessel, but by bad luck.

Gato-class submarines

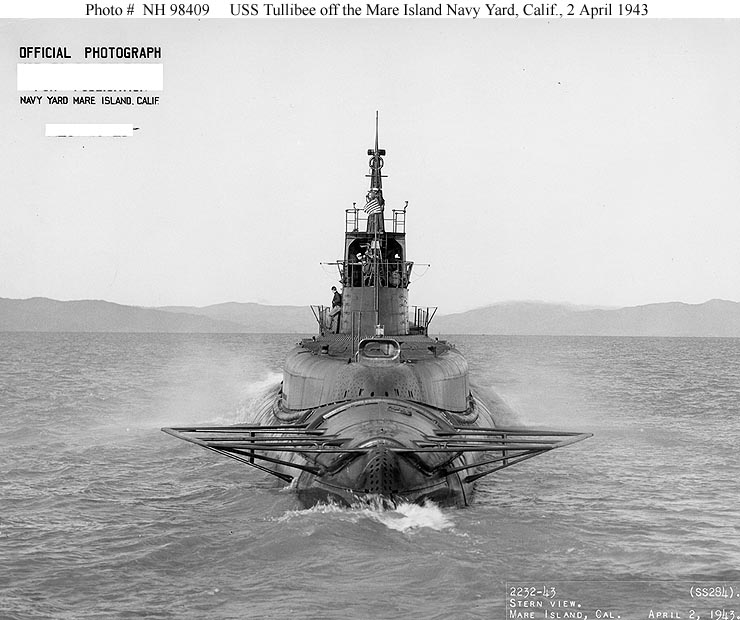

USS Tullibee (SS-284) was one of the U.S. Navy’s seventy-seven Gato-class submarines. These were the first American mass-produced submarines and were a realization of long-standing goals to make a submarine with a longer range and higher endurance. These qualities quickly became necessary to meet the demands of missions in the Pacific theater of World War II.

With a length of 311 feet 8 inches and total displacement of 2,424 tons, Gato-class boats were quite large. Since there was room for a huge fuel bunkerage, they were capable of conducting 75-day patrols from Hawaii to Japan and back.

Another significant improvement that increased the boat’s combat abilities was increased diving depth. Gato-class submarines were projected to submerge to a record depth of 300 feet, but in reality they were going even deeper.

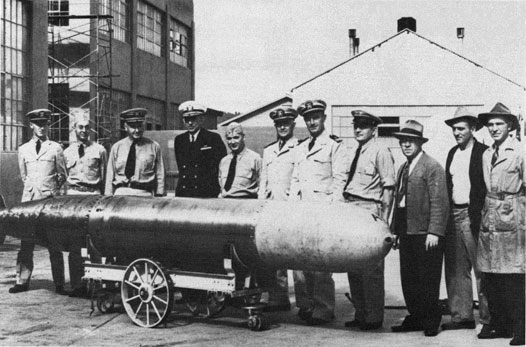

The submarines also had an improved armament, with ten torpedo tubes and twenty-four 21-inch Mark-14 torpedoes. Because patrols were so long, torpedoes had to be used sparingly. For that reason deck armament was improved with one 3-inch deck gun, one 40 mm Bofors gun, and one 20 mm Oerlikon gun.

The first Gato-class submarine to be completed, USS Drum (SS-228) was laid down just before the war on September 11, 1941. The production of the class lasted until April 21, 1944, when they were replaced with improved Balao-class submarines.

Along with the Balao-class boats, Gatos were the backbone of the U.S. Navy submarine fleet during the Second World War. With only 29 losses, the combined 197 submarines of these two classes made a large contribution to winning a war against the Japanese fleet in the Pacific.

USS Tullibee (SS-284)

USS Tullibee was launched from the Mare Island Navy Yard in California on November 11, 1942, and was commissioned on February 15, 1943. It was just in time for the tides of war to start changing in the Pacific.

After going through the required shakedown cruise, Tullibee sailed to Hawaii on May 8, 1943. Once there, the entire crew had to undergo further training, and the boat had to be tested even more. The result of the tests was two months spent in the Navy dockyard repairing the hull for air leaks, hardly a good omen.

Tullibee on war patrol

Things hardly changed when Tullibee went on its first patrol on July 19, 1943. It was tasked with patrolling the Saipan-Truk traffic lane, searching for Japanese cargo ships. The goal was to disrupt the supply lines of the Japanese stronghold at the Truk Lagoon, where the majority of the Japanese fleet was at the time.

Still inexperienced, Tullibee‘s crew (that consisted mostly of 19-year-olds) showed some confusion when the submarine got engaged in combat for the first time. On August 10, Tullibee spotted a convoy of three freighters with an escort. Commanding officer Charles F. Brindupke decided to attack and fired four torpedoes at two vessels.

However, the attack ended up with one of the Japanese ships ramming into Tullibee, damaging its main periscope. The submarine immediately dived and was attacked with depth charges by a Japanese escort ship. Tullibee managed to escape, but so did the convoy.

It took three attempts for Tullibee‘s crew to conduct a successful attack. On August 22, it sank a passenger-cargo ship and damaged one freighter. The submarine ended its first patrol on September 6 by returning to Midway.

Following patrols were more successful. During the 52 days of its second patrol in the East China Sea in October and November 1943, Tullibee had several successful attacks. It sank one passenger-cargo ship, damaged another, and damaged one tanker.

The third patrol saw Tullibee and two other submarines patrolling the region around the Mariana Islands, intercepting vessels sailing from Truk to Japan.

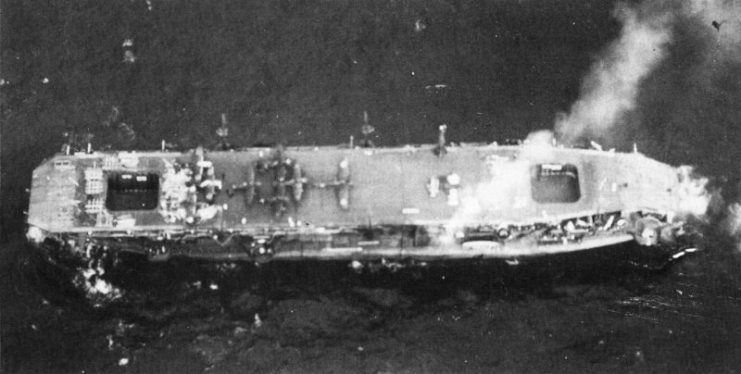

Besides sinking another freighter, Tullibee also managed to damage the enemy escort carrier Unyo. This was the longest of its patrols, lasting for 58 days from December 14, 1943, until February 10, 1944.

Eternal Patrol

It was March 5, 1944, when Tullibee left Pearl Harbor after almost an entire month of rest. A week later, it reached Midway, refueled and set out on its fourth patrol on March 14. The orders were to sail north of Palau Island to participate in Desecrate One — an operation by 11 aircraft carriers against Japanese forces at Palau. It was the last time the vessel was seen.

Tullibee was supposed to serve in a protective role, but it never appeared at its station. It was formally declared lost on May 15, 1944. Even though there was no report or even intercepted Japanese messages to confirm a loss, the sub was believed to have been sunk by an enemy vessel.

Cliff Kuykendall – the prisoner of war

The war continued, and the Tullibee crew of 60 men was written off. Their mourning families were denied any answer as to what had happened. But when the war ended. The answer suddenly came out of nowhere.

The Japanese government surrendered on September 2, 1945. Five days before, the occupation of Japan had begun. Allied soldiers being held in captivity in Japan were all set free. Most of them had been engaged as forced labor in mines across the entire country, such as the copper mine in Ashio.

Among the men who were set free on the 4th of September was Cliff Kuykendall, who had ended up in Ashio after spending 17 months working in several other mines as a prisoner of war. Before he was transported to Japan, he survived the torture while being held as a prisoner at the Island of Palau. He was even tied to a tree for three days while American bombs were falling all around the island during the Operation Desecrate One.

He arrived Palau on the Japanese destroyer Wakatake, which had picked him up in the open sea north of the island. He was the only survivor from the USS Tullibee.

After he was set free, Cliff revealed the mystery of the missing submarine.

Hit by its own torpedo!

On March 26, 19-year-old Gunner’s Mate 2nd Class Cliff Kuykendall was on lookout duty on the bridge when a convoy of a troopship, three freighters, and three escort ships was spotted on the radar. It was pouring rain but commanding officer Charles F. Brindupke was determined to attack.

It was only at the third attempt that he managed to fire two torpedoes at the troopship. Kuykendall was standing on top of the bridge waiting for the explosion when the submarine was struck by a huge explosion. Cliff went sky high and ended up in the sea.

As he was struggling to stay on surface, he watched as his boat was going down and his mates were screaming for help. It was only his lifebelt that kept him alive.

When all sounds were gone, Cliff remained alone, floating for the whole night. The next day he was picked up by the Japanese destroyer.

As he was reporting on what happened that day, Cliff was sure that Japanese escorts were far enough away not to be able to attack his submarine. It was not sunk by Japanese, he told. The only logical conclusion was that one of the fired torpedoes made a circular run and returned to hit and sink the submarine.

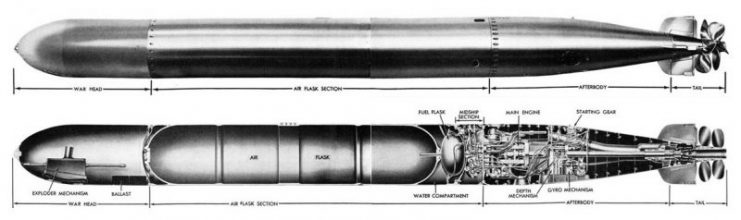

The Tullibee was armed with Mark-14 torpedoes, which were known to have such failures.

Mark-14: the torpedo that goes round

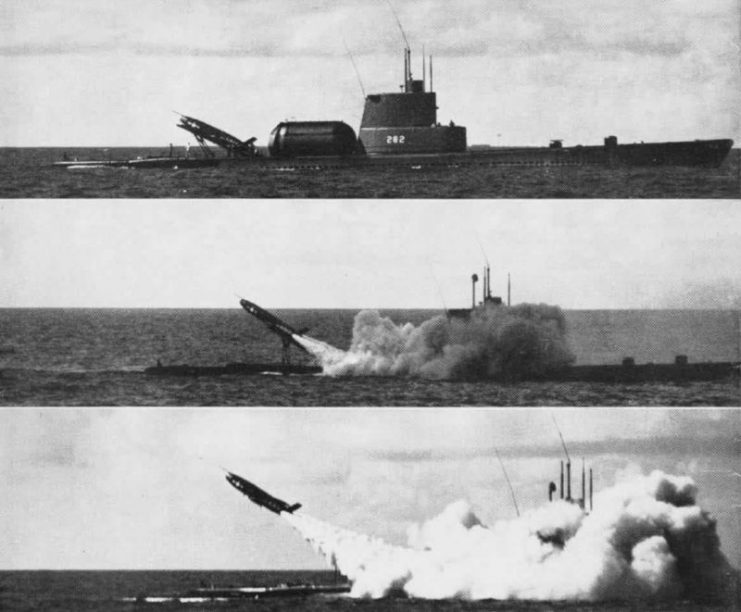

The weakest point of the US Navy submarine force was definitively the Mark-14 torpedo. It was developed during the Depression Era in the 1930s when the industry was down on its knees. This allowed the entire project to pass with numerous bugs unnoticed.

In short, the weapon was highly unreliable. It tended to run too deep, to explode prematurely or not explode at all. However, the most lethal drawback was the torpedo’s tendency to run a circular course that returned it to submarine from which it was fired.

The circular run was a result of the failure of the gyro system that was responsible for straightening the rudder of the torpedo once it was fired. If the rudder was not straightened, the torpedo wouldn’t make a straight course toward the target but would instead make a round trip back to the spot from which it was fired.

During World War Two, there were 24 recorded incidents of a circular run. In 22 cases, submarines managed to evade the torpedo. The USS Tang and USS Tullibee didn’t.