During WWII, many British servicemen became prisoners of the Germans. Some were captured during the fall of France and the retreat to Dunkirk. Others were the crews of planes shot down over Germany or specialists caught on commando missions.

The British military and intelligence services provided advice on how to help the men evade and escape their enemy. Without being on the inside, it was hard to offer guidance on how to escape a prison camp. However, there were plenty of lessons learned by former PoWs on how to behave while on the run.

Do Not March

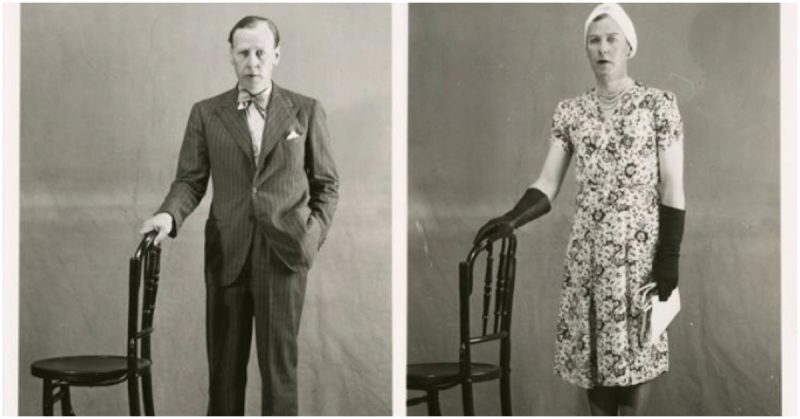

For centuries, marching had been drilled into military personnel. It was a way of instilling discipline and showing pride in their uniform. Even when not on the parade ground, soldiers and airmen tended to hold themselves upright and proudly. When trying to evade an enemy, it was natural for them to use a swift, determined stride, to get away quickly. It was not the way to avoid detection. An army training memo of July 1940 advised escapees to “adopt a tired slouch.” That way they would not draw attention or mark themselves out as military men.

Get on Your Bike

The same memo recommended that escapees try to “collect” a bicycle. Some prisoners had found a bike invaluable in making their getaway. The advantages of a bicycle were obvious. It enabled escapees to move faster without restricting them to roads. Unlike hitching a lift or using public transport, it did not involve interacting with other people who might notice an escapee’s accent.

No doubt unfortunate civilians were annoyed by the theft of their bikes, but with the fate of Europe at stake, it was not a high price to pay.

Do Not Wear a Watch

A wrist watch could be very conspicuous. Not everyone wore them, and they were distinct to each country. Some military personnel wore tough, or high quality watches to help them with their work. A watch might, therefore, identify its user as a person out of place, particularly while fleeing through a rural farming region.

A watch was also a valuable asset, so escapees were advised to keep it in their pocket.

Carry Your Bag Right

The smallest details could give an escapee away. Soldiers typically carried haversacks on their backs. French peasants, however, wore them slung over a shoulder. Escapees were therefore advised to wear them in such a way.

No Walking Sticks

The use of a cane or walking stick by a fit and healthy man was a relatively common sight in Britain, but not in Europe. They were told to ditch the walking sticks, which would mark them out as British.

Change Shoes

Durable, comfortable, high-quality boots are one of the most important pieces of equipment a soldier has. A lack of suitable footwear has severely hampered armies in conflicts such as the Crimea and the French Revolutionary Wars. Soldiers, therefore, take good care of their boots.

It would have been natural to stick with their military boots as quite often an escapee had to walk for hundreds of miles. However, army boots were a dead giveaway to a soldier’s identity. They were advised to get hold of locally popular shoes, such as the rope-soled shoes worn by French peasants. They would not be as ideal to walk in, but they would draw less attention.

Shave

The fashion among French peasants in the 1940s was generally to be cleanly shaven. PoWs on the run in France were advised to remove their beards so they would blend in.

Wear a Beret

To the modern ear, it sounds like a ridiculous cliché – wear a beret to look French. At the time, hats were commonly worn, and berets were hugely popular in rural French areas. With many escapees fleeing through France, the beret was an excellent choice of disguise.

Approach Priests

Early escapees found that priests were often helpful. They were sympathetic to those in need and held a position of responsibility within their communities. Although escapees were advised that priests could be helpful, they were required to approach them with care and avoid being seen publicly talking to one.

As always, staying inconspicuous was vital to staying alive.

Do Not Try to Escape On Your Own

From early in the war, escape networks were set up to help PoWs reach safety. Military personnel were given instructions on who to approach and when to enable them to connect with such organizations.

Once they had made contact, escapees hid and awaited further instructions. They were told not to try to escape back to Britain on their own. The French resistance running the networks knew their local area and were experts in their work. Servicemen stood a much better chance of escaping with them than without.

Obey Instructions

On the same basis, they were ordered to follow to the letter any instructions given to them during their escape. The lives and freedom of other escapees and resistance agents depended upon their actions. Following the advice of local experts was important.

Be Careful With Gifts

Throughout their escape, PoWs were told to be careful about giving gifts. Cigarettes and chocolate were valuable commodities in the prison camps, where they could be used to befriend and even bribe guards. In the outside world, they were even more valuable.

Chocolate was virtually unknown in Germany and occupied Europe due to wartime blockades, so was incredibly noticeable. Cigarettes, often being hard to get hold of, could similarly act as a giveaway. As could the nicotine stains on the fingers of Allied servicemen, who had regular access to them.

Source:

Ian Dear (1997), Escape and Evasion: PoW Breakouts In World War Two;