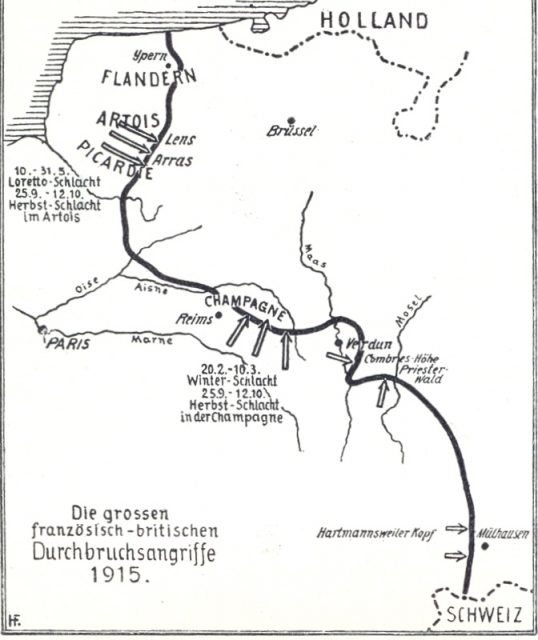

The goals of the First World War were more personal for the French than for their British allies. The Germans had invaded parts of France and continued to hold them for most of the war. The French were, therefore, eager to drive the Germans back, leading them to launch offensives such as the Second Battle of Champagne.

Planning the Autumn Offensive.

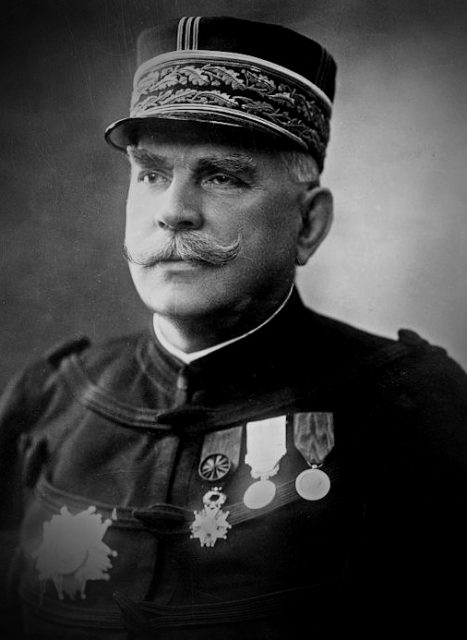

The Battle of Champagne was part of a great offensive planned by Marshal Joseph Joffre, the French Commander-in-Chief, for the autumn of 1915.

Joffre’s plan was for the Allies to launch two attacks at the same time, at separate points on the fighting front. An Anglo-French force would attack the Germans in the north-easterly region of Artois. Meanwhile, the French would launch an advance all of their own, an advance that became the Second Battle of Champagne.

The French Advantage

Joffre mustered 500,000 French troops in the Argonne, an area in eastern France. By concentrating all this manpower along a 10-mile section of the front, he created a situation where they outnumbered the Germans by three to one. Theoretically, it would give them the advantage in the ensuing battle, thanks to the sheer weight of manpower.

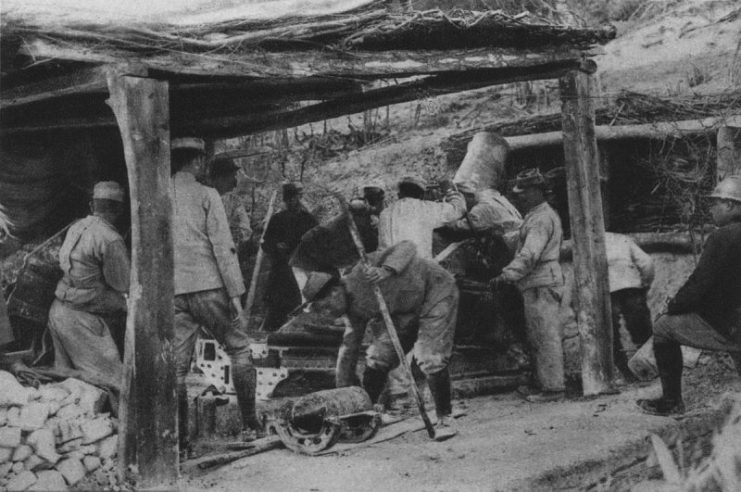

To make the most of this advantage, Joffre preceded the attack with a heavy bombardment. For four days, 2,500 French guns rained shells down on the German lines where the attack was due to take place. The ground was torn apart by explosives, turning it into a mess of dirt and shell holes.

Now the great advance could begin.

Into Action

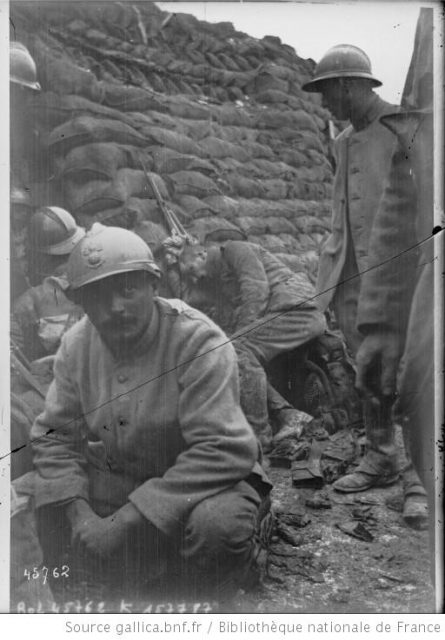

On the 25th of September, French troops poured out of their trenches and across no man’s land towards the German lines. As with so many frontal assaults of the First World War, their commanders had high hopes for the outcome.

As in so many frontal assaults, they were going to be disappointed.

Part of the problem was the same as in almost every battle of the war. The generals were convinced that heavy bombardments would devastate the defenders and smash their defenses, leaving them vulnerable to attack. But in reality, the men could weather these attacks. They headed into deeper dugouts, which the Germans were particularly good at building, and waited there for the artillery fire to end. There were casualties, but most men survived.

Instead of breaking the enemy’s spirit, prolonged bombardments acted as a warning. When the French shelling stopped, the Germans knew that an attack must be coming because they had seen this strategy before. They grabbed their guns, hurried out of their dugouts, and rushed to their places on the front line.

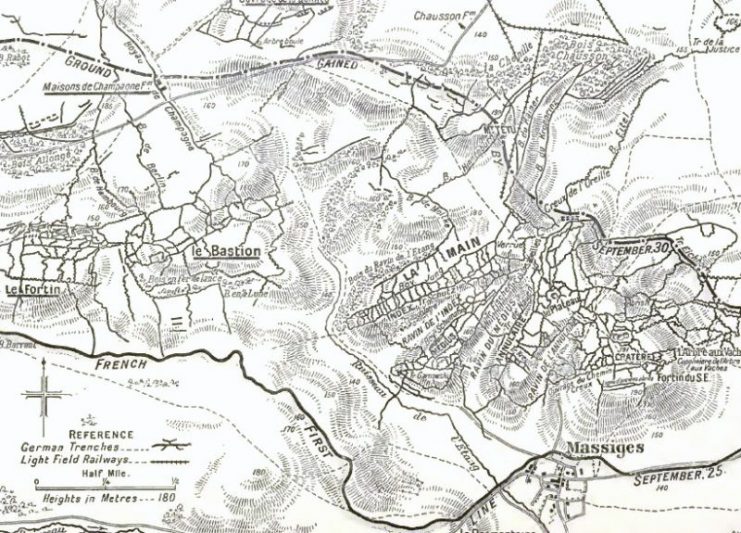

At Champagne, the Germans had the added advantage of holding the high ground. As the French charged, they did so uphill, into the mouths of enemy guns.

Limited Gains

20 French divisions attacked in the first wave, followed by another seven. Against them stood only six German divisions.

Given such numbers, it was almost inevitable that the French would gain some ground. Through trench fighting, they broke through the German front line in four places.

The Germans pulled back, using a strategy of defense in depth, with multiple layers of trenches manned by reserve troops. The French became caught up in trying to fight their way through the lines. They reached the German reserve lines in two places.

It was at these places that the Germans made their main stand. The barbed wire here was intact, unlike in parts of the front line. Anticipating the attack, the Germans had pulled their field artillery back to this line, along with some supporting troops. The French, halted by the barbed wire, came under heavy fire.

Pushing On

On the second day, the French attacked again. They broadened their foothold in the forward trenches until they faced the reserve lines along a 7.5-mile front. In one place, they even managed to fight their way into that reserve line.

Attacks against the reserve line continued over the next few days. On the 28th, the French made another breakthrough, taking control of part of the line. But this made them more vulnerable, as the trenches were on the reverse slope and so out of sight of supporting artillery. On the 29th, the Germans launched a counterattack and retook those trenches.

Attrition

Despite ordering all of his Eastern Army Group to send their artillery shells to the battle, Joffre was running out of ammunition for his big guns. With the troops stalled, he ordered the advance put on hold. The French would consolidate the ground they had taken while they waited for more ammunition to arrive.

Over the following days, the French made some smaller attacks against German positions. But the battle had lost its impetus and there was little to be gained in this way. On the 3rd of October, Joffre changed tactics, ordering his commanders to conduct a battle of attrition. This lasted for a further month with little achieved. On the 6th of November, Joffre officially called the attack to a halt.

Outcome

The Second Battle of Champagne was a huge disappointment for the French. They had expected to make a significant breakthrough but instead had been stopped by effective German defensive tactics. Some ground had been taken, but nothing significant. They had inflicted 85,000 casualties upon the Germans, capturing thousands of men and 150 guns. But in return, they had suffered 144,000 casualties of their own.

Despite this and the other offensives of 1915, the front lines barely moved that year on the Western Front. What the commanders considered bold tactics were just repetitions of what had gone before. There would be no retaking France’s lost ground through such assaults.