In April 2019 the last link to the fabled Doolittle Raiders from WWII was severed with the death of Lieutenant Colonel (ret) Dick Cole, who was co-pilot on bomber No 1 during that famous raid.

Cole will be buried in Arlington National Cemetery, but a memorial service is planned to be held on April 18th at Joint Base San Antonio-Randolph in Texas.

In 2016 Cole consented to an interview for HistoryNet.com about his life and the famous raid. He had been born and raised in Ohio, and said that as a child he would ride his bicycle to the Army Air Corps base at McCook Field so that he could watch the planes.

In November 1940, Cole enlisted in the Army Air Corps as he believed that it would be a good job while the country was in the grip of the Great Depression. After he completed his training, he was sent to Pendleton, Oregon to join the 17th Bombardment Group.

Early in February 1942, he was transferred to Columbia in South Carolina. On arrival, they saw a notice pinned to a board that asked for volunteers for a mission. It seemed everyone was keen to go on the mission, because the entire group volunteered for it.

Cole, who was aged 26 at the time, was one of the airmen selected and he was sent to Eglin Air Field in Florida for his training. Cole said in his interview that they were confined to their isolated barracks on the base and warned not to talk about their training. They only thing they knew was that the mission was to be dangerous.

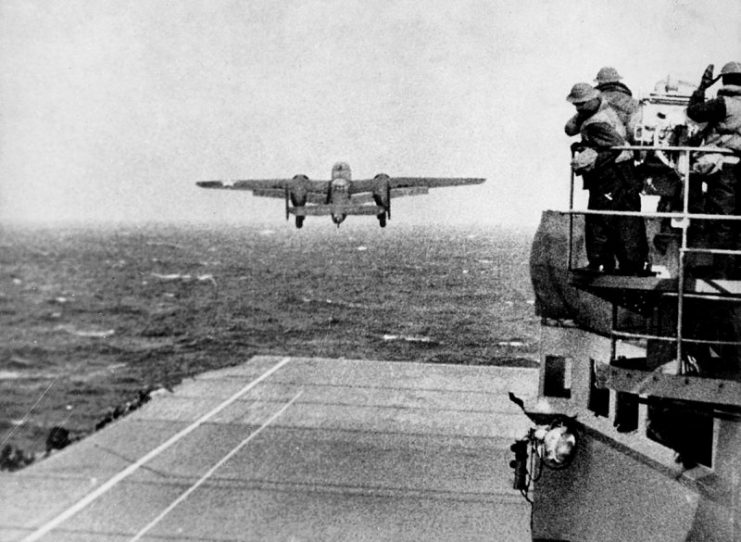

Under normal circumstances, a B-25 needed at least 3,000 feet to take off, but the group was trained to use only 500 feet. Then when future Navy Rear Admiral Henry Miller commenced training them to take off from an aircraft carrier, they guessed they were off to the Pacific to fight against Japan.

Cole, then a 2nd Lieutenant, was moved to co-pilot for Doolittle when the pilot with whom he was scheduled to fly fell ill as did the co-pilot that was flying with Doolittle.

All excess equipment, including the lower turrets and bombsights, was ruthlessly stripped from the planes. Additional fuel tanks were fitted to increase the fuel load to 1,100 gallons (which was double the standard capacity) and the aircraft were loaded onto USS Hornet. They sailed from Alameda, California on April 2nd, 1942, and two days later they were told that the target for their mission was Tokyo.

The announcement caused great excitement, but soon the realization of what they were getting into sank in, and the room became quiet.

When the flotilla ran into a Japanese “picket ship” and the weather deteriorated, with waves breaking over the bow and causing the planes to slide around on the deck, the decision was made that the raid would be launched early.

Navy Admiral William Halsey decided that the rough weather was in their favor, to a degree, as the strong wind increased the carrier’s speed from 20 to 35 knots, which would make the take-off a little easier.

After four hours of low-level flying at around 200 feet, the aircraft reached Japan. As the No 1 bomber, piloted by Doolittle and Cole, reached Tokyo the weather was clear, bright and sunny. Doolittle climbed to 1,500 feet and their bombardier, Staff Sergeant Fred Braemer, released the payload of bombs. Cole remembers being jostled around a little bit by anti-aircraft fire, but he didn’t think they had been hit.

Doolittle intended to land in Chuchow, China to refuel and then continue on to western China, but they ran into an enormous thunderstorm. The Chinese heard the engines of the plane and, thinking they were Japanese planes, turned off the lights on the runway. Doolittle and his crew had no choice but to fly on until they ran out of fuel and then bail out.

Fifteen of the aircraft reached China while the sixteenth landed in Vladivostok in the USSR. Of the 80 men who took part in the raid, 77 survived the original mission. Eight were captured by the Japanese and three of those eight men were executed. The airmen that landed in the Soviet Union were jailed for over a year before their “escape” was arranged through Iran.

Cole and the rest of the No 1 bomber crew were picked up by Chinese troops. After the raid, Doolittle was concerned that the strike had been a failure due to the high number of planes lost and the fact that the attack itself did very little damage and caused few casualties. He was completely wrong as the boost to the morale of the American people was considerable.

The raid also successfully sent a clear signal to the Japanese people that the Japanese islands were not safe from an American aerial attack and that the US was fully prepared to strike them. That caused the Japanese to pull back from India and Australia to boost their forces in the Central Pacific.

The Japanese believed the strike had been launched from Alaska, so they sent two of their aircraft carriers to patrol off the Alaskan coast. That would even the odds for the Americans during the battle of Midway.

After the raid, all the Raiders received the Distinguished Flying Cross, and Doolittle received the Medal of Honor. When Cole was asked what he thought of Doolittle, Cole said that he had “the highest order of respect from one human being to another” for Doolittle.

After the rescue, Cole continued serving in the Far Eastern theater of China, Burma, and India. In June 1943 he volunteered for Project 9, which led to the creation of the 1st Air Commando Group.

It is apparent that Cole continued to enjoy great popularity in the Air Force right up until the day that he passed away. In 2016, he was given the honor of appearing on stage to announce that the Air Force’s next stealth bomber, the B-21, would be named the Raider. In 2017 the home of the 319th Special Operations Squadron at Hurlburt Field in Florida was renamed the Richard E. Cole Building.

When Cole turned 103 on September 7th, 2018, Air Force Chief of Staff General Dave Goldfein along with his wife, Dawn, called to wish him a happy birthday.

Read another story from us: The American Doolittle Raid And The Brutal Japanese Reprisals

Cole was a much-decorated officer, and by the time he retired he had accumulated an impressive list of decorations. He had a Bronze Star, the Air Force Commendation Medal, and the Distinguished Flying Cross with two oak leaf clusters. Additionally, in 2014 he was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal by President Barack Obama.

To the end, this gentleman of the skies was humble and said that he and his fellow raiders did not feel like heroes. He said that they were just doing their job and were part of a much bigger picture. They were happy to help when America needed them.