There were plenty of positions during World War II that put a serviceman’s life at risk. Arguably one of the worst was being the ball turret gunner. Small, tight, difficult to escape from and with minimal visibility, the ball turret was the definition of danger. Designed in the 1930s, it was equipped on many US aircraft during the conflict. Eventually, it was abandoned in future aircraft designs, leaving the immense dangers it posed behind.

Which aircraft equipped the ball turret?

The ball turret was initially developed by two separate companies, Emerson Electric and the Sperry Corporation. Development of the latter’s design was soon halted, with Sperry’s design being preferred.

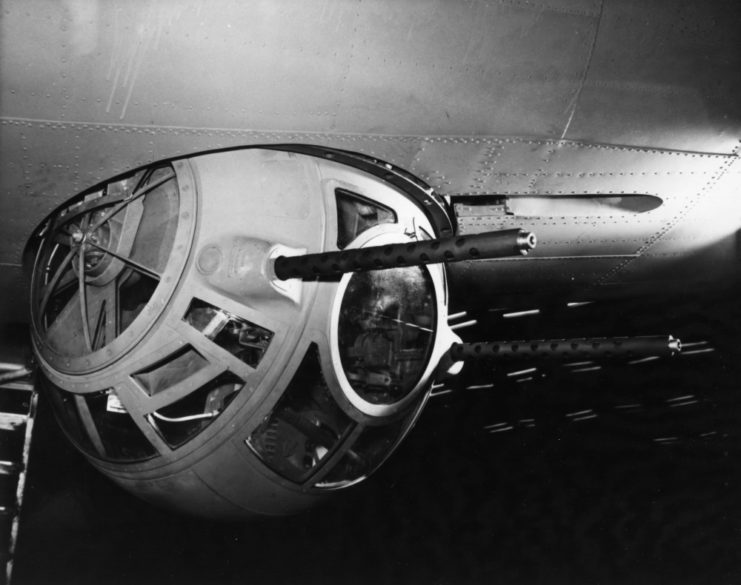

The ventral ball turret was a hydraulically-operated, altazimuth mount addition to the two main aircraft that housed it: the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress and Consolidated B-24 Liberator. The implement was also equipped by the PB4Y-1 Liberators operated by the US Navy, as well as the B-24’s successor, the Consolidated B-32 Dominator.

Ball turret specs

Despite being rather small at only four feet across, the ball turret still packed a punch. There was actually a reason for its compact design, as it reduced drag while in the air. They were surrounded by armored plates, which kept them protected during mid-air enemy action. On the flip side, their position underneath meant they were vulnerable, should the aircraft be shot down.

It was equipped with two Browning AN/M2 .50-caliber machine guns, a Sperry optical gunsight and two ammunition cans with 250 rounds each. The turret also rotated 360-degrees, allowing the gunner to locate targets and stay on them, regardless of their position. Given the cramped nature of the ball turret, the Brownings’ handles were difficult to maneuver, so a pulley system was developed to allow for easier operation.

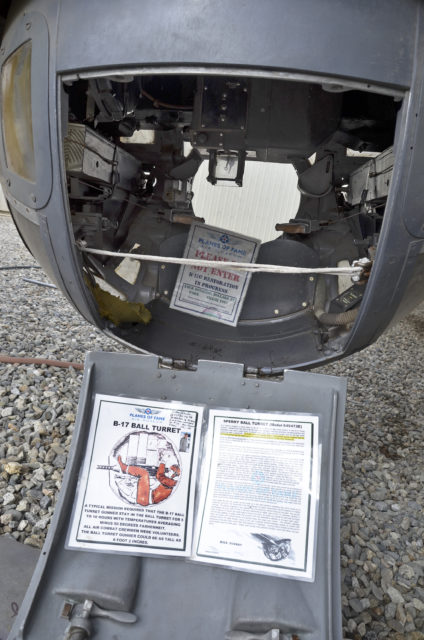

Ball turret designs varied, depending on the aircraft. The B-17’s conventional landing gear meant the implement featured a non-retractable mount, while the B-24’s tricycle landing gear required the installation of a vertically retractable mount. This kept the ball turret from hitting the ground during unstable takeoffs and landings.

Best airmen for the job

Aerial gunners were trained in US Army Air Corps schools that popped up across the United States in 1941. At their height, the schools were pumping out 3,500 graduates a week, producing approximately 300,000 by the end of the Second World War.

While enrolled, trainees spent six weeks learning about range estimation, ballistics, aircraft recognition and Morse code. It was an intense position, meaning they had to be prepared to make quick and often life-saving decisions. To ensure they could shoot targets in the air, recruits first underwent shooting practice on the ground, before advancing to tester aircraft.

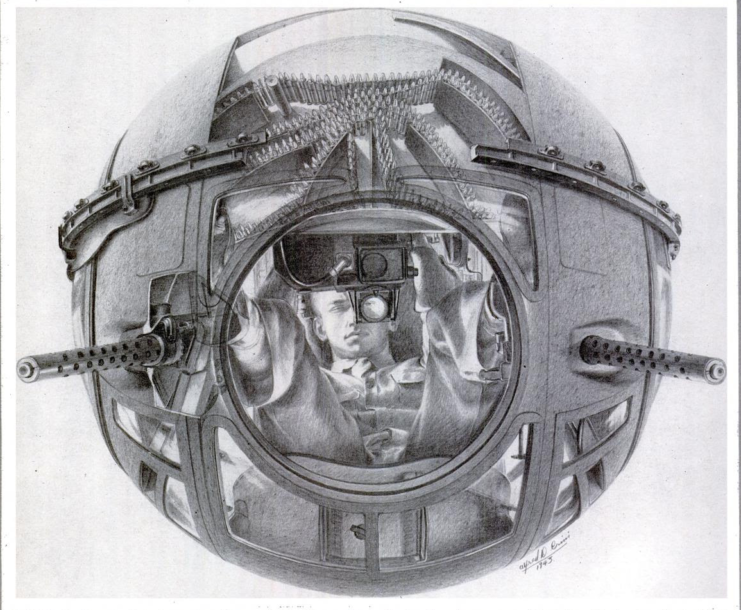

Due of the size of the ball turret, the gunners best suited to take the position were typically the smallest airmen in a crew; taller individuals would have struggled in the cramped, tiny spaces. Wearing flak jackets and electrically-heated flight suits, the gunners were ready to enter the uninsulated sphere, which, if they didn’t react quick enough, would make them vulnerable to enemy fire.

Taking on the enemy in a cramped ball turret

To climb inside the ball turret, gunners had to enter through a door located in the floor of the aircraft, positioning the ball so its guns were pointed toward the ground. They then placed their feet on the heel rests inside and lowered themselves. To fit, they assumed a fetal-like position, with their knees bent close to their body and their backs and heads up against the rear wall. Some had to maintain this position on missions of up to 10 hours, a rather uncomfortable prospect.

The gunner held two joysticks in either hand, one to pivot the turret ball and the other to trigger the firing mechanism for the Browning machine guns. Foot pedals on the floor controlled the gunsight between their legs and operated an intercom, which served as the only form of communication between them and the rest of the crew.

Small windows allowed the gunner to see below the aircraft, but not above.

Problem with parachutes

The small size of the ball turret didn’t allow for additional equipment to be housed within. As a result, the parachute needed in the event the aircraft was gunned down was placed just outside of the turret door.

Unfortunately, this wasn’t a very good place for it, as the gunner needed to open the turret door, enter the fuselage and strap themselves in – all before the aircraft crashed. To negate the danger, some gunners wore a chest parachute, but this typically wasn’t the norm.

Dangers of landing

Another problem with ball turrets was they never fully retracted into the aircraft. This meant that, not only where they easy to spot and a potential target for enemy aircraft, they also exposed gunners to potentially fatal situations.

When not in full operation, the turrets still stuck out of the bottom. This made it difficult for the aircraft to land safely. It was critical the ball turret gunner assume a particular position for belly landings – otherwise, the sphere would hit the ground far before the landing gear and pose a threat to their safety. As well, when landing on water, the turret was the first part to become completely submerged; while the implement was meant to be waterproof, this wasn’t the case.

Poet Randall Jarrell, who served in the US Army Air Forces, outlined the terrifying and grim nature of being a ball turret gunner in his poem, The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner. He wrote, “When I died they washed me out of the turret with a hose.”

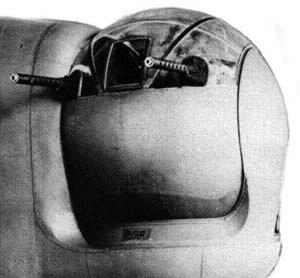

ERCO developed a second-generation ball turret

Toward the end of the Second World War, ERCO’s ball turret became the preferred implement for two bombers operated by the US Navy, the Consolidated PB4Y-1 Liberator and PB4Y-2 Privateer. Unlike previous iterations, this ball turret served two purposes during low-level attacks on Japanese targets: fire suppression and strafing for anti-submarine warfare, as well as defense against bow attacks.

More from us: The Hughes H-4 Hercules Was An Absolute Mammoth Of An Aircraft

Similar to earlier ball turrets, the ERCO version’s machine guns were operated by handles. They used the standard Navy Mk 9 reflector sight, allowing for adequate aiming capabilities.