It is an amazing testament to the true goodness of humanity that even in the throes of battle, compassion can rise in the hearts of men.

Though soldiers fight together for a united cause, each is an individual with his or her own values at the core that cannot ever be fully controlled. Whether it is for codes of honor, personal sympathy, and empathy, or something else – soldiers sometimes treat their enemies with respect and brotherly love that should be and often is commended.

Kinship and Understanding at Gallipoli

In WWI Turkey, in May of 1915 at what became known as the Anzac Cove on the Gallipoli Peninsula in Turkey, Anzac (Australian and New Zealand Army Corps) troops are battling it out with the Turkish. Men on both sides are terrified of death and destruction both from gunfire and from fear of being buried alive in the trenches.

The Turks have been mostly ahead in this campaign, but when they try to take the beachhead here, they lose around 3000 men – most of them falling in the strip between the lines known as “no man’s land.” The Turks fall back, but continue fighting from their trenches.

Within a couple of days, the odor of death coming from no man’s land becomes overpowering. There is talk of the potentiality for further disease spreading from it. The men on both sides have already suffered great illness including dysentery and diarrhea, and more sickness cannot be tolerated.

Via the Red Cross and the Red Crescent, commanding officers of both sides reach an agreement to allow the Turks to bury their dead on May 20. Because trust is an issue in war, the Anzacs become suspicious that the Turks were using it as an opportunity to advance their goals and open fire on them briefly.

A few days later, a brave group of Turks approaches the Australian line under gunfire until the most courageous of their party comes forward alone and is led blindfolded through an avenue of Anzac soldiers to meet with General Birdwood and form a formal truce. Each side, on May 24th, will create a boundary of Red Cross or Red Crescent flags, respectively, on their front line, through which the enemy will not cross.

On that day, Turks and Anzac soldiers meet and bury the dead together, talk socially, and share small luxuries like cigarettes.

“It was a beautiful day, and exactly at 7.30am the Australians and the Turks began the work of burying the dead between the lines. The Australians had received orders not to go beyond the Red Cross flags and the Turks had received similar instructions as regards their flags, but it soon became apparent that neither side intended to strictly observe the arrangements, because each side fraternised at once, exchanging greetings and cigarettes and souvenirs.” – Colonel Arthur Wellesley Hyman

“This whole operation was a strange experience – here we were, mixing with our enemies, exchanging smiles and cigarettes, when the day before we had been tearing each other to pieces.” –Albert Facey

“We walked from the sea and passed immediately up the hill, through a field of tall corn filled with poppies, then another cornfield; then the fearful smell of death began as we came upon scattered bodies. We mounted over a plateau and down through gullies filled with thyme, where there lay about 4000 Turkish dead. It was indescribable. One was grateful for the rain and the grey sky. A Turkish Red Crescent man came and gave me some antiseptic wool with scent on it, and this they renewed frequently . . .

The Turkish captain with me said: “At this spectacle even the most gentle must feel savage, and the most savage must weep.” . . . Our men and the Turks began fraternizing, exchanging badges, etc. I had to keep them apart. At 4 o’clock the Turks came to me for orders. I do not believe this could have happened anywhere else. I retired their troops and ours, walking along the line. At 4.17 I retired the white-flag men, making them shake hands with our men. Then I came to the upper end. About a dozen Turks came out. I chaffed them and said that they would shoot me the next day. They said, in a horrified chorus: “God forbid!” The Albanians laughed and cheered, and said: “We will never shoot you.” Then the Australians began coming up, and said: “Good-bye old chap; good luck!” And the Turks said: “Oghur Ola gule gule gedejekseniz, gule gule gelejekseniz” (“Smiling may you go and smiling come again”).” – Aubrey Herbert

There are still other great acts of kinsmanship during Gallipoli.

Private Robert Eardley saved the life of a Turkish soldier, and the favor was returned. Eardley had come upon another Brit about to bayonet the Turk, who was without weapons and was already greatly wounded. Eardley talked his fellow soldier out of killing a defenseless man and later, as he was sitting there in the trench with the wounded Turk, dressed his wounds, gave him a pillow, cigarette, and drink.

Later, after a counter attack, Eardley woke up with a severe bayonet wound in a Turkish trench being filled in with dirt. Lying with other bodies, he had been taken for dead. He stood up and saw himself surrounded by Turks ready to stick him through again.

Suddenly, the Turkish soldier he had saved appeared and threw himself in front of Eardley to protect him.

His friend spoke to the commanding officer who then said “English, get up. No one will harm you. You would have died only for this soldier – you gave him water, you gave him smoke, and you stop bleed. You very good Englishman.”

Eardley said of the moment they parted ways “I shook hands with this Turk (and would give all I possessed to see this man again). As our hands clasped, I could see he understood for he lifted his eyes and called ‘Allah’ and then he kissed me (I can feel his kiss even now on my cheek as if it were branded there or was part of my blood).”

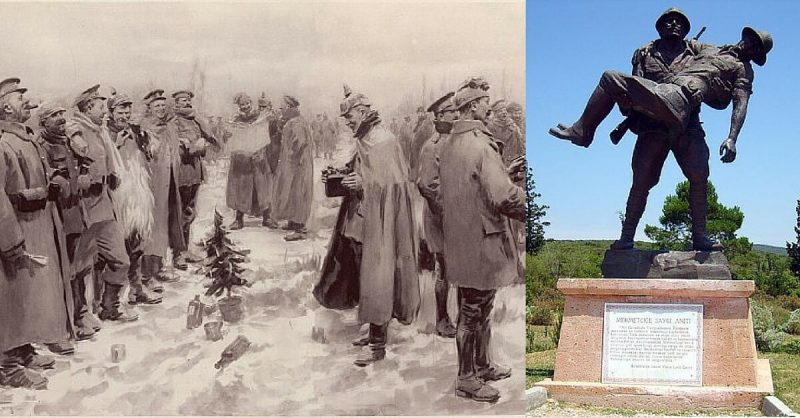

A statue remains at Gallipoli called The Respect to Mehmetçik Memorial which depicts a Turkish soldier carrying a wounded Australian. It commemorates a moment in which the Australian soldier was lying wounded in no man’s land. The firing was going on around and over him until that Turkish soldier lifted a white flag on his bayonet. The fighting stopped long enough for him to run out, pick up the wounded Australian, and carry him to the safety of the ANZAC trenches before returning to his own.

When the fighting was over and done with, both sides respected each other greatly, and the friendship was not lost:

“Those heroes that shed their blood and lost their lives … You are now lying in the soil of a friendly country. Therefore rest in peace. There is no difference between the Johnnies and the Mehmets to us where they lie side by side now here in this country of ours. You, the mothers, who sent your sons from faraway countries, wipe away your tears; your sons are now lying in our bosom and are in peace. After having lost their lives on this land, they have become our sons as well.” – Ataturk, Turkish leader

“I reckon the Turk respects us, as we respect the Turk; Abdul’s a good clean fighter – we’ve fought him, and we know.” – ANZAC poet, Lieutenant Oliver Hogue

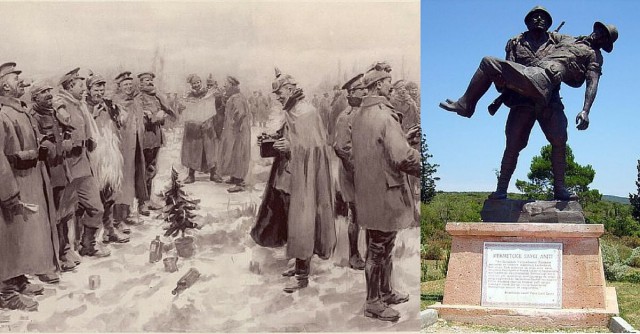

The Christmas Truce

This story is more well-known than the first, but is always worth reflecting on.

In December of 1914, Pope Benedict XV’s call for a Christmas ceasefire is denied by the battling nations of WWI.

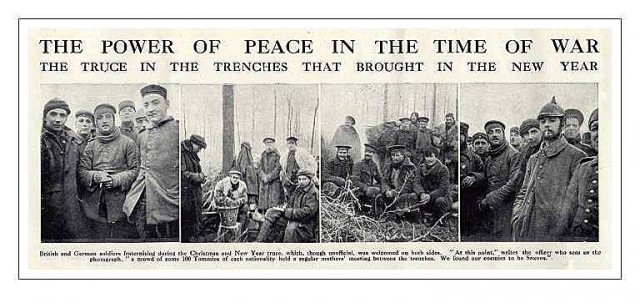

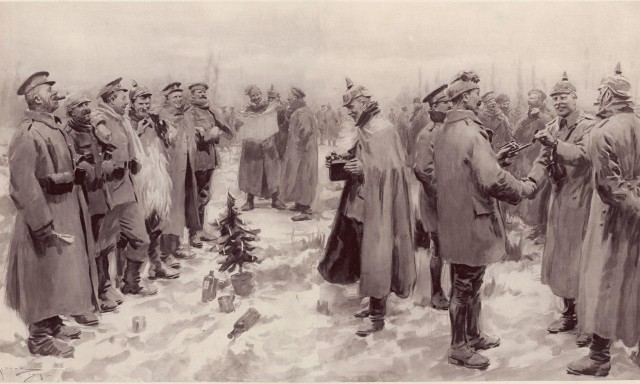

That Christmas Eve, as the Allied soldiers are huddled in their trenches thinking of home, they hear the strains of Silent Night coming across no man’s land from the German lines. At first, they wonder if it is a trick to get them to come out.

The Allied soldiers hesitantly and then fully join in on the song. All of the troops, both German, and Allied are singing Christmas carols together through the night.

Christmas morning the Allied soldiers wonder what will happen next. Slowly, they raise up their heads and quickly duck back down. Raising them again, they see the Germans with their arms raised, waving.

Soldiers from each side carefully trek to meet each other in the middle with wariness and caution. When they do finally meet, they shake hands.

These warring enemies have put aside their commands to spend a holy holiday in friendship. Men on both sides are aware that they are participating in what may be viewed as treason, but for this one day, it is worth it.

There is exchanging of small gifts like cigarettes, shared holiday sweets, and games and more caroling. They enjoy Christmas as closely as they can to the real thing back home.

British soldier, Frank Richards, said this of the day:

“The German Company Commander asked Buffalo Bill (Richard’s commanding officer) if he would accept a couple of barrels of beer . . . He accepted the offer with thanks and a couple of their men rolled the barrels over and we took them into our trench. The German officer sent one of his men back to the trench and he appeared shortly after carrying a tray with bottles and glasses on it. Officers of both sides clinked glasses and drunk one another’s health. Buffalo Bill had presented them with a plum pudding just before. The officers came to an understanding that the unofficial truce would end at midnight. At dusk we went back to our respective trenches.”

On a humorous note, is Frank’s account of the end of the truce:

“During the whole of Boxing Day we never fired a shot, and they the same, each side seemed to be waiting for the other to set the ball-a-rolling. One of their men shouted across in English and inquired how we had enjoyed the beer. We shouted back and told him it was very weak but that we were very grateful for it. We were conversing off and on during the whole of the day.

We were relieved at dusk by the battalion of another brigade . . . We told the men who relieved how we had spent the last couple of days with the enemy . . . They told us that by what they had been told, the whole of the British troops in the line, with one or two exceptions, had mucked in with the enemy . . .They also told us that the French people had heard how we had spent Christmas Day and were saying all manner of nasty things about the British Army.”

- http://www.gallipoli.gov.au/Anzac-battlefield-sites-walk/site-9-johnstons-jolly.php#

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Third_attack_on_Anzac_Cove

- http://www.gallipoli.gov.au/Anzac-battlefield-sites-walk/site-9-johnstons-jolly.php#

- http://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=11243692

- http://www.smh.com.au/news/world/gallipolis-one-brief-shining-moment/2008/05/18/1211049068574.html?page=2

- http://www.gallipoli.gov.au/explore-Anzac-sites/turkish-soldier-memorial.php

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Respect_to_Mehmet%C3%A7ik_Monument

- http://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/news/nsw/the-aussie-pm-turkeys-hero-and-their-unbreakable-bond-forged-at-gallipoli/story-fni0cx12-1226766683343

- Rogan, Eugene -The Fall of the Ottomans: The Great War in the Middle East. 2015. Basic Books

- http://www.history.com/topics/world-war-i/christmas-truce-of-1914

- http://www.eyewitnesstohistory.com/trenches.htm

- Richards, Frank, Old Soldiers Never Die (1933)