Every new weapon changes the nature of battle in some way. Certain weapons have come to define war, and to transform the way it is fought from one era to the next.

Sword

The Bronze Age was a period of slow but massive transformation for humanity. Metal working allowed tools of greater sophistication and specific purpose. From swords to ploughshares, the world was being turned on its head.

The invention of the sword was a gradual process, emerging from changes in knives and daggers. Longer blades were manufactured in the Middle East from late in the 3rd millennium BC, appearing in Pakistan, China, the Greek islands and many places in between. Europe’s earliest unambiguously identifiable swords have been dated to around 1700 BC in Crete.

From there, swords spread throughout the world and down the centuries, becoming ever more varied and specialised. But they always retained a special significance. Unlike other early weapons such as bows and spears, they had no role in hunting. These were weapons whose entire purpose was to kill other human beings.

For the first time, war had specialist tools.

Cannon

Though there were many innovations in the three millennia between the sword and the cannon, gunpowder weapons brought transformations on a whole new scale. The first to do this were cannons.

Song dynasty China was a hotbed of experimentation in gunpowder weapons. In the 13th century AD, these innovations led to the emergence of the cannon, which spread quickly through the Middle East and into Europe. Featuring in the Battle of Ain Jalut in 1260, a century later it had completed its journey across Eurasia, appearing in the English armies of the Hundred Years War.

Cannon ended the defensive superiority of stone castles. Sieges bombardments b

ecame more effective, and artillery appeared for the first time on the battlefield.

It was at sea that the greatest change took place. With the aid of cannons, naval warfare shifted from close quarters boarding actions – essentially infantry battles at sea – into ships firing at range, seeking to cripple or sink each other.

Musket

The first widely used gunpowder weapon for individual soldiers, the musket was a terrible weapon to use one-on-one. Slower to load and fire than conventional bows, prone to misfires, and wildly inaccurate, alone the early muskets were more bark than bite.

Used as a mass, they were devastating. A large block of men with muskets could easily hit another block of men, with terrifying effect. And though the longbow or crossbow could be just as deadly as these early guns, the musket was far easier to use. Quicker, easier training meant that more men could be usefully armed. The great equalizer, muskets paved the way for the ever-escalating armies of the early modern era, and the conscriptions that would eventually follow.

Ring Bayonet

The greatest drawback of muskets was that they were of little use in close quarters. Without blades, points or purpose built crushing surfaces, their wielders were at a disadvantage up close. As a result, they were fielded alongside infantry armed with melee weapons. 17th century Europe saw infantry fielded in alternating blocks of pikemen and musketeers. Half the army was no use at long range, and the other half vulnerable at close quarters.

Becoming popular in the late 17th century, the bayonet was a blade that could be attached to the end of a musket, transforming it into a stabbing weapon. Musketeers now had a weapon with enough reach and deadly potential to hold their own against cavalry charges and other close quarter attacks. Early bayonets used a plug system, being shoved into the end of the musket, but this prevented their users from firing just before close combat. The offset ring bayonet, which quickly became popular among European armies, let generals equip all of their infantry the same way, becoming deadly both at range and up close.

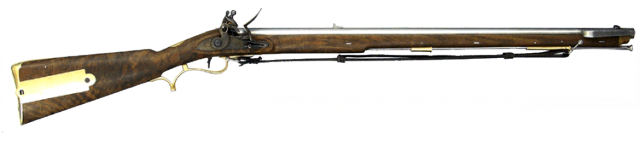

Rifle

Invented in late 15th century Germany, but not widely used until the 19th century, the rifling of gun barrels allowed a further transformation in their use.

Smooth bore weapons such as the musket were wildly inaccurate. By adding grooves to the inside of the barrel, rifling spun the ball, making it travel in a far straighter line. Though initially used by the same large blocks of infantry as the musket, the rifle turned infantry warfare back around. With suitable training and experience, men with guns could accurately hit one another.

Rifling led the way to modern infantry warfare, with individual targeting, loose formations and even snipers.

The Interrupter Machine Gun

It took centuries of development for cannons to allow ships to fight one another, instead of being fighting platforms for groups of infantry. Under the intense pressure of World War One, it took only a year for airplanes to undergo the same transformation.

In the early stages of the war, pilots fought in the skies for the first time. Initially used to scout out enemy forces, they soon became scenes of combat. Pilots took pistols and bombs into the sky, then mounted weapons on their aircraft to attack each other. But they faced a problem – to sight along a weapon, they needed it mounted in line with the aircraft, and doing this created the near certainty of shooting out their own propeller blades.

Several less reliable options were tried before the Germans introduced the Fokker-Leimberger interrupter gun. First fielded in July 1915, its ingenious mechanisms prevented it from firing while the propeller was in the way. Pilots could now use their whole planes as deadly weapons. True aerial warfare had arrived.

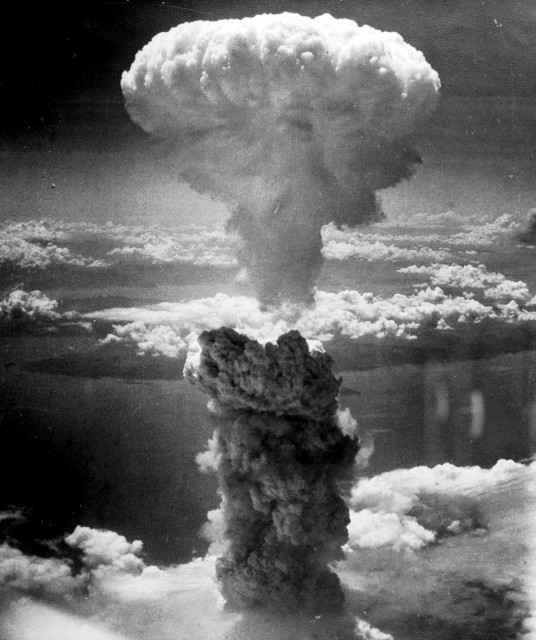

Atom Bomb

Though only used in anger twice, the atomic bomb transformed the strategic and political face of war. The huge scale of its destructive power led to a scaling back of conflicts, as the most powerful militaries in the world stopped fighting each other for fear of mutually assured destruction. Instead they reverted to proxy wars and local conflicts, throwing their influence and resources into other people’s fights in Africa, Asia and Latin America. The increasingly massive wars the great powers engaged in from the 18th to the 20th century came to an end, for now at least.

The shadow cast by the cloud over Hiroshima had ended the vast conflicts the great powers once engaged in. A weapon need not be used to make the battlefield a very different place.