A major conflict in Europe from the 14th to the 15th century was The Hundred Years War. The House of Plantagenet, respectfully the Kingdom of England, fought against the House of Valois – the Kingdom of France – for 116 years. They clashed in a total of 55 battles, for control over the lands of France.

The warfare that took place from 1337 to 1453 resulted in few peace treaties and territorial changes in the two kingdoms. However, we can point out 3 significant English victories that changed the situation on the island and the continent during the exceptionally long war.

The Battle of Crécy

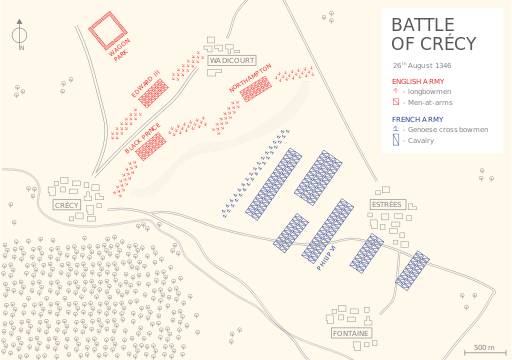

On the 26th of August 1346, 12,000 English longbowmen defeat a much larger French forces of cavalry and crossbowmen, near the village of Crécy , Northern France. The Battle of Crécy, won by the Englishmen under the command of Edward III, would be marked down in history as an occasion when the use of the longbow completely turned the tide of battle. Edward was also able to make use of the higher ground, putting the French at a further disadvantage.

The English army was divided into three divisions, the back of the center led by Edward, the vanguard by the infamous Edward of Woodstock – also known The Black Prince – and the rear by William de Bohun, Earl of Northampton. All three had longbowmen wings and an infantry center. Their tactical advantages lay in the speed and range of each longbow, their position on the hillside and, perhaps most importantly, the fact that the troops were well rested.

The french were not so lucky. Their force was exhausted, working with poor terrain and, at least in part, comprised of crossbowmen – a unit without the same range as the English longbowmen. Their first line carried crossbows, followed by several cavalry troops under the leadership of Philip VI of France and John of Bohemia.

In no time, the Genoese were routed and thrown into disarray and under caught beneath volleys of English arrows. The cavalry units launched an attack on the center, but it soon became clear that they stood no chance of breach the enemy position. In the end, Philip fled the battle and his flag the Oriflamme was captured. Estimations show that no more than couple of hundred Englishmen were killed, while the casualties of the french go beyond the thousands. The victory gave Edward III the opportunity to besiege the french village of Crécy and for Calais to remain in English hands for two more centuries.

Battle of Poitiers

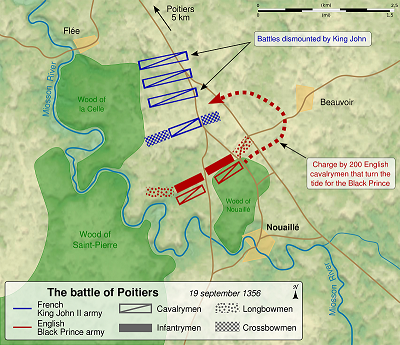

Some 10 years later, on 19 September 1356 near Poitiers in France, another major battle between the English and their enemies took place. Edward the Black Prince again led a decisive victory against a much larger French army, which would throw the Kingdom of France into chaos.

As the French knights launched their attack on the Englishmen, thinking their foes were withdrawing, they were caught in a deadly rain of arrows, demobilizing and killing many of their horses. Even though the armor gave the knights some advantage, as it was thick enough to protect them from the English arrows, it was not enough. The cavalry units a disastrous end.

After the failed cavalry charge, the infantry also tried to somehow break the strong English defensive line. They failed, however, and many of the troops began to panic and flee.

The French King Jean II of France and his youngest son Philip were captured. Up to 2000 members of the nobility were captured, including knights and figures within the Royal Family. The English casualties were kept to the minimum, reaching no more than a few hundred.

Battle of Agincourt

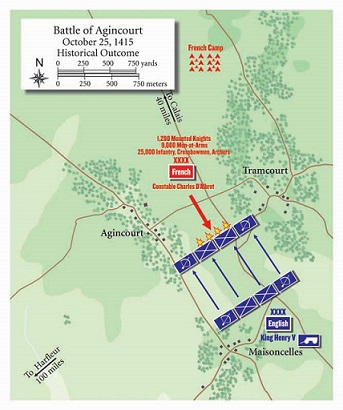

Another brilliant English victory through the course of the Hundred Years War was obtained at the Battle of Agincourt in October 1415. English Bowmen, under the command of Henry V, managed to defeat a French army led by Charles d’Albert near Agincourt in France. Once again the French army was superior in numbers to their English enemy, and once again the outnumbered English held their own.

In the early morning, on the 25th day of the month, Henry deployed his loyal bowmen on two flanks, under the command of Sir Thomas Erpingham, leaving his center as three divisions, the middle led by himself and the two vanguards by the Duke of York and the Baron of Camoys.

On the other side of a freshly plowed land was the French army. In contrast with the usual traditions of warfare, French noblemen stood on the front lines, eager to win glory in their fight against the English. The French were confident that their superiority in numbers and the greater amount of noblemen in their ranks would lead them to a resounding victory.

However, the use of English longbows, now defended from any French cavalry advance by rows of wooden stakes, proved deadly . The French cavalry had to retreat, while the infantry that took their places fared no better.

The muddy ground, the terrified horses around them and the tremendous volleys of English arrows proved disastrous for the French infantry. Even after the longbowmen ran out of arrows and engaged in hand-to-hand combat, the encumbered French forces were decimated. In just three hours, the battle was over.

Several hundred French knights were taken prisoner, many to be slaughtered later, while around 10,000 were killed in battle. More than 1,500 noblemen were captured and at least 100 royals and bannermen were dead. The Englishmen suffered incredibly small loses, especially in comparison with their enemy.

This decisive English victory was crippling for the Kingdom of France and Henry V was able to capture a large area of land. He also found a bride – the french princess Catherine of Valois. Their marraige turned a new page for the Hundred Years War, and the son of the English king and the French princess was announced heir to the throne of France and England.

Finale

On the 8th of May 1429, the English unsuccessfully laid siege to the city of Orleans. In the end, they were repelled by an army under the command of a 17-year-old peasant girl. Joan of Arc lifted the siege, marking a turning point in the conflict. This great success for the French greatly increased their morale and, in the middle of summer 1453, the Hundred Years War culminated in the Battle of Castillon. The English were beaten decisively, and the French reclaimed their lost territories.