War History Online presents this Guest Article from Charley Valera

Today’s WWII veteran Tech Sergeant Joseph R. Chiminiello shared many personal stories and photos for the book My Father’s War: Memories from Our Honored WWII Soldiers. Here’s a few first-hand excerpts from one of The Greatest.

On November 3, 1944, Chiminiello went from New York to Liverpool, England, riding high in the Queen Mary. “It was beautiful. I had the ride of my life. My father was a shipbuilder. I was in the aft deck; all I had to do was walk out and get on the backside of the ship. I had to duck when the waves came over me. But the bow of the Queen Mary was right in the water. I loved it.” He remembered heading into Liverpool and seeing the huge barrage of balloons protecting the ships from enemy strafing. It was a preview of the war to come for the nineteen-year-old Chiminiello.

Joseph Chiminiello was part of the United States Army Air Force, Eighth Army, 389th Bomb Group, in Hethel, England. He was assigned in the “low ball,” low turret of a B-17 Flying Fortress and then into the B-24 Liberator…Chiminiello laughed as he recalled his place in the plane. “I was all rolled into a ball,” he said. “I had the best view. All I had to do was turn it and look around.” At 5 feet 6 inches and weighing in at 140 pounds, Chiminiello learned how to squeeze into the ball turret and sit there for hours and hours.

Chiminiello remembered certain details of several missions. “Yeah, I remember it like it was yesterday,” he said, more to himself than to me. “We were in formation. One plane was hit. The wing fell right off the plane. It was shot and folded right up. One of the guys was burned really badly and got thrown out of the ship. He was the only one. The B-24, you don’t get out of it—that’s the idea. If you’re lucky, you make it; you had to be [in a] damn good position. You either got thrown out or something. You do carry the chutes; we’d see a few go down. The idea was to count them, see who’s gone and who isn’t gone. But most of the time, the B-24 wasn’t the safest ship.”

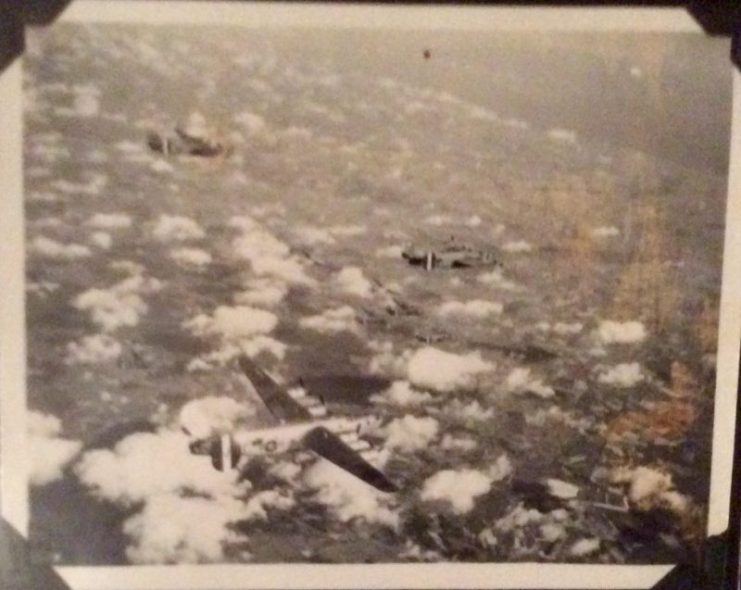

They had two long missions, Chiminiello recalled, one to Austria and another to Poland. “Twelve hundred miles each way. Those were bad. The weather was cold as hell. Twelve hours per trip. We’d get a tankful of fuel that would take us. I sometimes wondered where they got all the gas. We didn’t eat, we didn’t do anything, and we just flew. They gave us three pieces of candy. I could see the war going on down below. We could see the land. I had to keep the turret moving. There was one that was going to come after me, but I showed him I was awake and a sharpshooter. It didn’t matter to me what he did. The sights had a line in them. You could frame the plane coming in.” From his position in the turret, he’d make sure all the bombs would drop properly. He’d watch them fall far below on their targets.

Another mission ended tragically for many in his formation. “One guy got hit by Germans. He hit the plane and then he [the plane that was hit] hit the lead ship, jumped up and hit the deputy lead, and jumped up and hit the lead of the next group. One guy took out four ships, forty men. You don’t get out of the 24. It was tough.” He confessed, “The turret is not the safest place to be when the ship is going down. You just don’t get out. It’s a horrible place to be.

“The weather there was bad, very bad. Lots of times, we’d get into formation and all you could see was the underbelly of the other planes. All you could see was under. The pilots couldn’t even see. It was all foggy. When you get the weather [briefings], you don’t know for sure what you’ll get until you get there.”

Chiminiello and crew flew twenty-eight missions before their first leave. “That was bad. I didn’t like that, but they wanted to get the war over with.” He flew a total of thirty missions as required and was released on April 21, 1945. “We were a very lucky crew.” Three weeks before the war ended, Chiminiello finished his tour of duty. He was in London celebrating when they heard Germany had surrendered. If needed, he was ready to go to Japan on the B-29s.

Upon returning, he admitted, “I dropped away. I never got interested in the war anymore. Later, they were kind of talking about it more. I’d like to forget the damn thing.” Chiminiello continued, “When we came home, no one ever questioned us … what we put up with, what we did. That was a stunner. Like there was no war.”

Charley Valera is the award winning author of My Father’s War: Memories from Our Honored WWII Soldiers, copies are available at Amazon, BN.com. View many of the interviews on YouTube. Signed copies are available only Here.