The front line did not even seem to move, while millions of soldiers were dying in trenches in horrible conditions, no mattered whether they were French, German or British. It was extremely cold, always raining and always surrounded by mud, rats and death.

“When the world is red and reeking, And the shrapnel shells are shrieking, And your blood is slowly leaking, carry on,” once wrote the great poet of the First World War, Geoffrey Studdert Kennedy, better known as “Woodbine Billy”, who chose to express himself through writing the stories he lived while he was in the trenches. “When the broken battered trenches, Are like the bloody butchers’ benches, And the air is thick with stenches, carry on,” continued his poem.

A few months after the war started, the Allied troops found themselves somehow trapped along the conflict’s Western Front, so they had to be fast and find a way to protect themselves from the enemy. Therefore, soldiers used a huge line of trenches, which measured around 700 kilometres from the North Sea through France to Switzerland, and which was to be dug in by soldiers for three years. The number of casualties they recorded every day was far more than the steps they would take in stopping the Germans from advancing. It looked like things weren’t moving on at all.

The very first trenches were poorly done and they most often looked like shallow holes, becoming better over the months that followed. They would usually dig them in zigzag, so if a German soldier would somehow get in, he couldn’t fire all along the length of the trench he was in.

The distance between enemy lines was sometimes very short, somewhere between 10 to 12 metres, therefore, barbed wire came useful in surrounding the ditches and slowing the Germans from advancing, the Global Post reports.

Whenever it rain, the trenches got flooded and they needed to be scooped out most of the times, while the wall collapsed, creating a mess of mud, which would later on freeze during the winter and which made living in the trenches harder and death much easier for soldiers.

“The rank stench of those bodies haunts me still, and I remember things I’d best forget,” wrote Siegfried Sassoon, English soldier and poet, who served on the Western Front during the First World War.

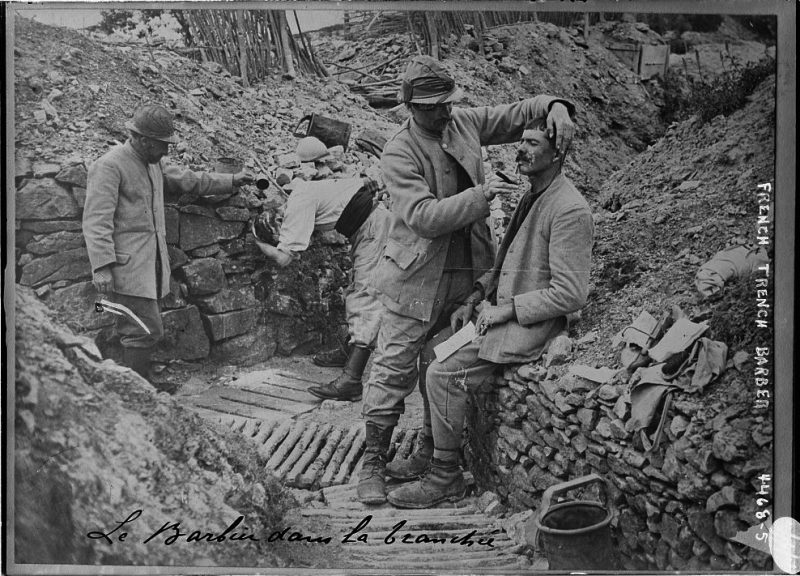

Mornings were terrible. After a pre-dawn “stand to arms” and a quick inspection, both sides would have breakfast during an unofficial agreement, some kind of “live and let live” truce.

//