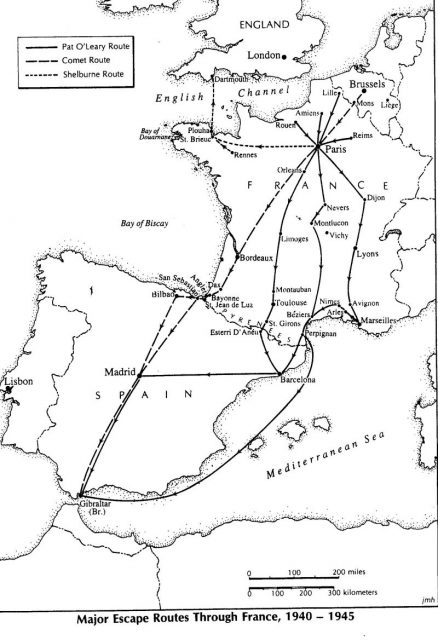

During the Second World War, many brave people risked their lives working in resistance groups. One of the ways in which they served was by running escape lines, secret networks that helped downed airmen and escaped prisoners of war (POWs) to escape the continent. With remarkable skill and courage, they kept these servicemen hidden and returned many of them to the fight.

Captain Ian Garrow

A British officer, Garrow became separated from the army during the fall of France in 1940. He managed to evade the Germans and the Vichy authorities as he crossed the country, eventually reaching Marseilles. There, he found shelter in a seaman’s mission before heading towards the Pyrenees and escape to neutral Spain.

On the way to the mountains, Garrow changed his mind. He turned around, returned to Marseilles, and there created the PAT line. PAT would eventually become one of the most important escape networks of the war, smuggling many Allied servicemen out of France across the Pyrenees.

Garrow himself was arrested by the Vichy authorities in October 1941. Just over a year later, as the Germans moved into Vichy France, it became clear that prisoners like him would be in great danger. Members of his network broke him out of jail and out of the country. He returned to Britain and became part of MI9, the secret service tasked with supporting escape and evasion.

Albert Mair Guérisse

A Belgian Army medical officer, Guérisse escaped to Gibraltar after his country fell to the Nazis in the summer of 1940. There, he joined the crew of a French cargo ship which became part of the British Royal Navy. They were given assumed names, with Guérisse serving as Patrick O’Leary.

The British started using this ship to transport agents into France and extract escapees. In April 1941, while rescuing a group of Polish troops on the run from the Nazis, Guérisse and several others of the crew were captured. They all later escaped and most returned to England. Guérisse stayed in France to help others get away.

He was recruited to the PAT line by Garrow, who needed a fluent French speaker to help run things. After Garrow’s arrest, Guérisse became the head of the PAT line.

Guérisse ran the line successfully for a year and a half, expanding its operations and helping hundreds escape. He was the mastermind behind Garrow’s jailbreak. But traitors infiltrated the line and eventually the authorities caught up with him.

On the 2nd of March 1943, the Germans arrested Guérisse in Toulouse. He was tortured for information about others in his network, which he refused to give up. He was put in a concentration camp, but survived the war, becoming a highly decorated hero.

Andrée de Jongh

Known as Dédée by friends and family, Andrée de Jongh was working as a nurse when the Germans invaded her home city of Brussels. Inspired by the example of First World War nurse Edith Cavell, she decided to help British servicemen and Belgian volunteers to escape the continent so they could keep fighting. She got together a group of other young people and started running what would become known as the Comet line.

Jongh’s network soon started to expand. Members of her family, including her father Frédéric, played an important part. The home of her aunt, Elvire de Greef, became a critical step on the route to safety, as a base near the Franco-Spanish border.

Jongh escorted her first group of escapees all the way from Belgium, across Spain, and to the border before handing them to a Basque smuggler. They reached Spain but were arrested there and interned.

To make sure that didn’t happen again, Jongh escorted the next group across the border herself. There, she made contact with the British Vice-Consul at Bilbao, Arthur Dean. After some initial skepticism, the British started funding the line and coordinating with Jongh to retrieve escapees.

Jongh recruited a remarkable network of young men and women who were both inconspicuous and quick-thinking, vital skills in people smuggling. She also found an excellent Basque guide, Florentino Goicoechea, to help them across the mountains. Together, her network saw around 800 evaders and escapees to freedom.

Like the PAT line, Comet was under constant threat from the Nazis. Many members were arrested, among them both Jongh herself and her father. She was interrogated 21 times but was saved from execution by conflicts between the Gestapo and the Luftwaffe’s intelligence service. The latter sent her to a concentration camp and “lost” her, apparently to spite their rivals in the Gestapo. Frédéric wasn’t so lucky. He was one of 23 Comet volunteers shot by the Nazis. Another 133 died in concentration camps.

After the war, Jongh and several other Comet members were awarded the George Medal, Britain’s highest award to a civilian for bravery.

Hugh O’Flaherty

The Right Reverend Monsignor Hugh O’Flaherty was an Irish priest living in Vatican City, an enclave of neutrality in Axis Italy. He was made secretary and English interpreter to the Pope’s representative to Allied POW camps in Italy. Though fiercely anti-British, he became a supporter of the Allied cause, a position that eventually cost him his job in the prison camps.

Following the Allied invasion of Italy in September 1943, many Allied prisoners escaped the camps. A number of them sought shelter in the neutral city. O’Flaherty became the head of an ad hoc organization helping them to hide from the Vatican and German authorities.

He worked with the British and American ministers to the Vatican, and later with Major Sam Derry, an escapee who he recruited to run the operation under an assumed identity. Despite run-ins with the authorities, O’Flaherty kept the organization going until the Allies liberated Rome in June 1944. By then, they were sheltering 3,925 escapees and evaders from over 20 countries.