Seventy-four years ago this month, Operation Overlord was launched and the fighting in Normandy began. This operation was so important and so monumental that everyone involved in the planning of it knew that they would, in the parlance of 2018, have to “think outside the box”. As history will show, the Allies became especially good at that, especially in regard to the Normandy invasion.

The artificial Mulberry harbors, an entire ghost army (complete with radio traffic, a commander, and inflated tanks, trucks and planes), General Percy Hobart’s “Funnies”, the tanks and other armored vehicles designed to clear minefields and other German obstacles, the American DD floating tanks (okay, some of these ideas didn’t pan out that well), and many others… all of these were designed to circumvent obstacles, both natural and man-made.

Four years of the First World War and five years of the Second had taught all sides the absolute necessity of a large and continuous oil supply. The British had sent the bulk of their own army to the Middle East in 1940 to protect the lifeline of the Suez Canal and the oilfields of the region.

Hitler had divided his forces in southern Russia in the summer of ’43 in order to seize the Soviets’ oilfields in the Caucasus. Many American lives were lost in the bombing raids on the German oilfields at Ploesti in Romania in the summer of 1943. Oil was crucial.

A quote attributed to Napoleon has it that “An army marches on its stomach.” In the 20th century, an army marched on its oil and gasoline supply. The planners of Operation Overlord knew they had to get oil and gas to the beachhead area as quickly as possible.

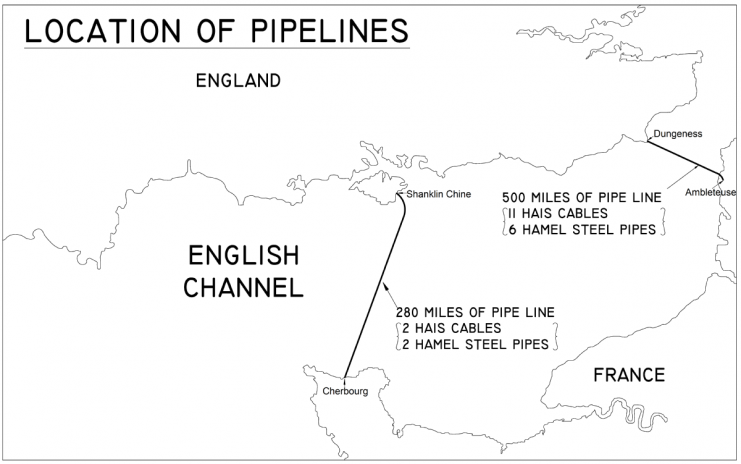

Part of the solution was “Operation PLUTO”. PLUTO was a code-name/acronym for “Pipeline Under-water Transport Of Oil”. Some list the name as “Pipe Lines Under The Ocean”, but this is incorrect.

The idea belonged to Arthur Hartley, chief engineer of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, who worked hand in hand with Admiral Louis Mountbatten, who was the Chairman of Anglo-Iranian, as well as being the Chief of Combined Operations.

Command was concerned that within the confines of the Channel, German U and E-Boats, as well as the Luftwaffe, would attack slow-moving tankers. Additionally, the allocation of shipping, especially tankers, was a major concern: more of them were needed in the Pacific, where the laying of a pipeline was an impossibility.

Two types of pipeline were planned for use on PLUTO; the HAIS type (for Hartley, Anglo-Iranian, Siemens, the company whose telegraph pipeline was modified for PLUTO), and the HAMEL type (standing for a combination of the names of the two chief engineers, Hammick and Ellis).

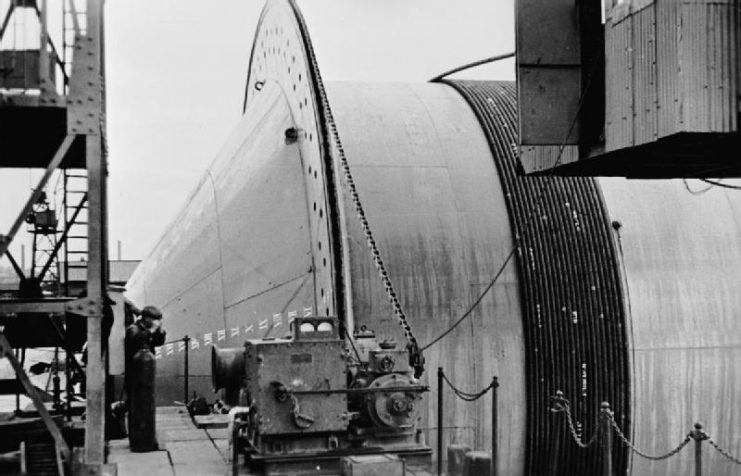

The HAIS type was flexible, which was needed, especially at the beginning and end of the pipeline, but contained lead – a lot of lead, which was prohibitively expensive and needed elsewhere. The HAMEL type was lighter and made from steel and other cheaper materials.

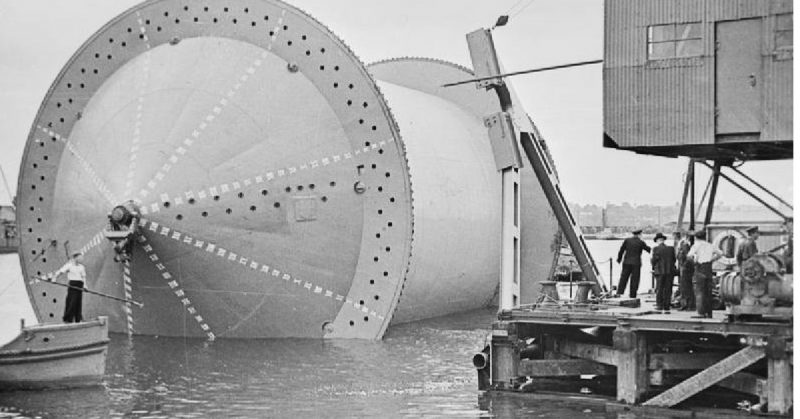

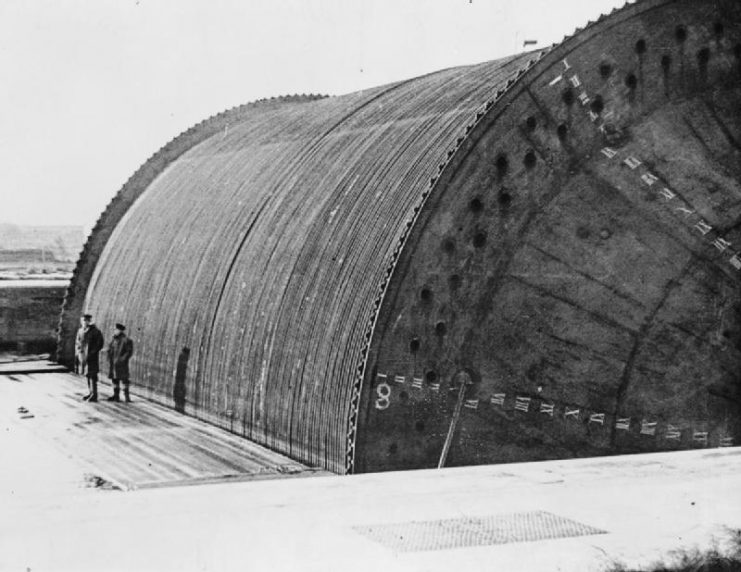

To lay and carry the pipe on the Channel floor, the CONUNdrum was developed. A clever play on words, the CONUNdrum was a giant cylinder thirty-foot in diameter and weighing two hundred and fifty tons, onto which the pipe was coiled. The drums were towed out to sea, trailing the pipeline behind it – one giant CONUNdrum could carry an astounding ninety miles of pipeline!

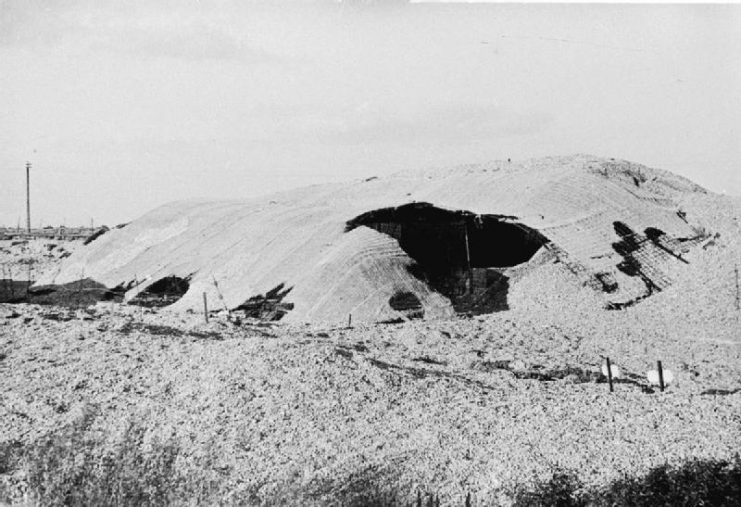

Oil and gasoline don’t simply flow from one end of a pipeline to another. Powerful “triple ram” pumps were used on the coast of England to get the fuels across to the continent. The planning to locate the pumps and pipeline and disguise them in plain sight – as an ice cream parlor or hotel, for example – is a story unto itself.

Unfortunately for the planners of PLUTO, the combination of resource allocation, time, money and development meant that the pipelines would not be in place until after D-Day.

PLUTO was directed at the Normandy beaches. The goal of was to supply the D-Day beachhead with petroleum products in the immediate aftermath of the invasion, in these terms, PLUTO was a failure.

Even after it was laid, only a small fraction of the oil needed by the Allies in Europe reached the D-Day beaches. From June to October 1944, when it was needed most, PLUTO only supplied 0.16% of all the fuel used by the Allies in Normandy. The rest came via ship through Mulberry – the threat from the German Navy and Luftwaffe never materialized.

However, other pipelines using the same technology were later laid from the UK to Cherbourg (Operation BAMBI), and Boulogne (DUMBO). Eventually, as the Allies advanced across France, DUMBO became the main petroleum artery from England.

After the war, economist D.J. Payton-Smith studied the pipeline project and came to this conclusion: “PLUTO contributed nothing to Allied supplies at a time that would have been most valuable… DUMBO was more valuable, but at a time when success was of less importance.”

By war’s end, the pipelines and technology behind PLUTO had delivered nearly 144 million US gallons of fuel to Europe.