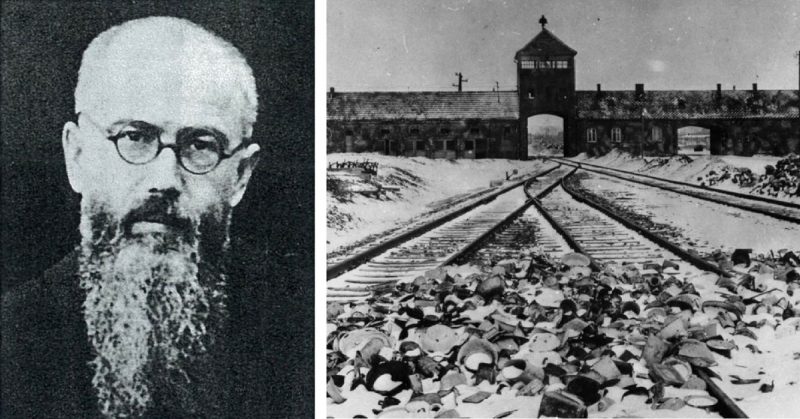

Undoubtedly, Auschwitz is considered to have been one of the most horrific places in the world. It also produced some incredible acts of human kindness.

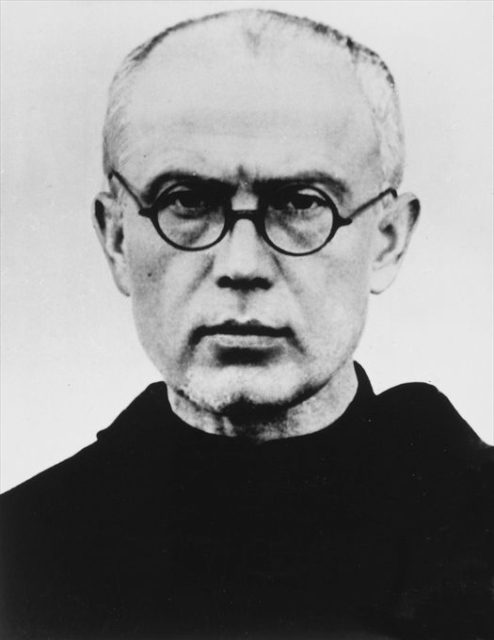

Although the secular history books often do not mention him, Maximilian Kolbe has his own following within circles of Catholicism. In October 1982 he was canonized as the patron saint of prisoners, drug addicts, the pro-life movement, journalists and even families. At the time of his canonization, the pope declared he was the patron saint of “our difficult century.”

The Making of a Saint

Maximillian Kolbe, born in 1894, was a Polish Franciscan friar. He was religious from a young age. At the age of 12, he received a vision of the Virgin Mary, who offered him two paths in life – one of purity and one of martyrdom. He accepted both.

A year later, Kolbe and his brother enrolled at the Franciscan seminary where he professed his final vows in 1914. He was well educated attending the Pontifical University in Rome where he earned degrees in philosophy and theology. During that time he became heavily involved with the work of what he called the “Army of the Immaculate One,” intended to convert enemies of Catholicism, particularly Freemasons.

Kolbe was ordained as a priest in 1918. Following his education, he returned to an independent Poland in 1919. He was very active in his hometown near Warsaw, where he founded a monastery and other organizations and publications as well as a radio station. In the 1930s, he traveled extensively in East Asia, including Shanghai and Nagasaki, working as a missionary. In 1936, however, his ill health forced him to return to Poland.

Wartime Effects

After WWII had broken out, Kolbe and a few other priests remained in his hometown monastery where he organized a makeshift hospital. He was arrested in September 1939, briefly held for several months, and then released in December. The Germans gave him the option to sign the Deutsche Volksliste as he was half-German by birth and, could claim rights as a German under Nazi rules. However, he was very adamant he would not do so. The Germans allowed him to continue his publishing work although, on his release, he used it to begin printing anti-Nazi publications.

Kolbe set about doing more work to save his people, but this time, he did much more than establishing a hospital. He and other monks at his monastery worked to shelter refugees from the rest of Poland, and they hid as many as 2,000 Jews during the Nazi invasion.

In February 1941 the Gestapo shut down the monastery and arrested him and his fellow monks. He was sent to Pawiak Prison, before being transferred to Auschwitz.

A Priest in Auschwitz

During his time in the concentration camp, Kolbe continued his role as a priest, but it caused problems for him. There were many instances where he was subjected to harassment and violence, including beatings and lashings. Once he had to be taken to the prison hospital.

In July 1941 several prisoners escaped from the camp, so the deputy commander picked ten men to be punished, to discourage others. They were placed in an underground bunker and not given food or water until they starved to death.

One of the men chosen was Franciszek Gajowniczek. He was a Polish army sergeant who had been captured in Slovakia. When learning about his fate, he reportedly cried out, “My wife! My children!” Kolbe volunteered to die in his place.

The assistant janitor at the camp later reported that Kolbe led the other prisoners who had been chosen in prayers when in the underground bunker.

Kolbe outlived the other nine prisoners. He remained calm throughout the experience and was found by his guards to be either kneeling or standing in the middle of the cell at all times. The guards eventually tired of waiting for him to die, and gave him a lethal injection of carbolic acid. He calmly took the injection, and his remains were cremated.

Gajowniczek, the man he saved, was transferred to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp in October 1944. He had spent five and a half years under Nazi rule inside the walls of various concentration camps. He was able to reunite with his wife after the war, but unfortunately, his children had been killed.

Honors Received After Death

Kolbe received beatification and canonization. Initially, there was some controversy over whether or not he would be canonized for his martyrdom. Some people argued that his death was not directly related to persecution based on his Christianity. It was eventually decided that the Nazi regime itself was a source of hatred against religion.

When Kolbe was beatified for his martyrdom, Gajowniczek was present, as a guest of Pope Paul VI in the Vatican. He was also a guest of Pope John Paul II, when Kolbe was canonized, in 1982.

Gajowniczek lived to be 93 years old, more than 50 years after Kolbe saved his life from the Nazis.