January 17 of this year marked the 100 – year anniversary of the most successful intelligence operation of the First World War that wasn’t surpassed until British code breakers cracked the Enigma code during the war that followed, almost a quarter-century later.

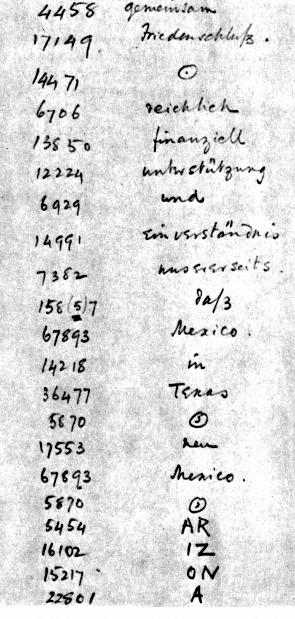

The Zimmerman telegram, which invited the Mexican government to side with Germany, urged the country to attack the United States in return for the states of Arizona, New Mexico and Texas.

When made public, the telegram helped draw the United States into the war, helped by senior officials to exploit public opinion.

On that fateful day in 1917, Nigel de Grey walked into his superior’s office in the Admiralty, Room 40, the epicenter of British code-breakers, and asked his boss if he wanted to bring the United States into the war effort.

The question was unnecessary since the answer was already known: with America in the war the stalemate on the Western Front would end. DeGrey said he had an astounding message that might accomplish the goal if a way might be found to use it.

The day before, Germany’s foreign minister, Arthur Zimmermann, sent a coded message that had largely been decoded by British code-breakers, to his country’s ambassador in Washington.

DeGrey concocted a scheme to use the telegraph as a way to alter the course of WWI.

German telegraph cables moving through the English Channel had been severed at the war’s start by a British ship. As a solution, Germany often sent its messages in code using neutral countries.

Germany had persuaded U.S. President Wilson that retaining channels of communication would help shorten the war. The United States agreed to forward German diplomatic messages from Berlin to its embassy in Washington.

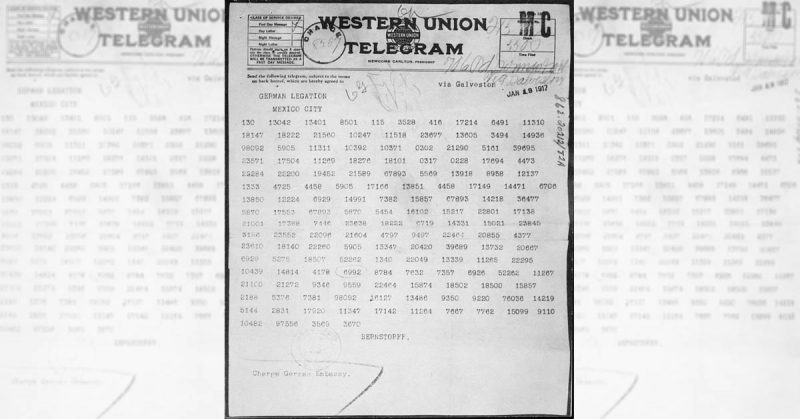

The message, known to this day as the Zimmerman Telegram, had been delivered, in code, to the American Embassy in Berlin, at 3 p.m. on Tuesday, January 16.

That evening, it was moving through another European country, then to London before being sent to the State Department in Washington.

From there, it would ultimately arrive at the German embassy on January 19, to be decoded and then recoded and sent using a commercial Western Union telegraphic office to Mexico, arriving hours later.

Due to their interception techniques, British code-breakers read the message but not in its entirety, 48 hours before the intended recipients.

An encrypted message about attacking the U.S. was actually passed along U.S. diplomatic paths.

Unknown to the Americans, Britain was spying on the United States and its diplomatic traffic.

But how could Britain use this information? Doing so would reveal that they were decoding German messages and that they had gotten the message by spying on the country it hoped would be an ally?

Britain assumed, correctly, that Germany’s declaration of unrestricted submarine warfare permitting attacks on merchant shipping would be sufficient to propel America into the war.

When the indications were that an extra incentive might be required, it was decided to use the Zimmerman Telegram. Room 40 asked one of its contacts to obtain a copy of anything sent to the German embassy in Mexico from the U.S. This revealed another copy of the telegram.

Britain could claim, plausibly, this was how it obtained the message and avoided the problem of admitting it was spying on supporters.

In time, the U.S. got its own copy of the telegram from the Western Union office. De Grey decoded the message in front of a U.S. embassy representative in London. Technically, this meant all parties could claim that it had been decoded on U.S. territory.

Britain also had to convince its ally that the message hadn’t been fabricated as part of a scheme to get them into the war.

The telegram was then leaked to the American press and published on March 1, 1917 (credit was given to the American Secret Service instead of the British to bypass awkward questions of British manipulation.)

Skepticism evaporated when Zimmerman himself took the unusual step of confirming he had sent it. Thirty days later America was in the war.

It would be an exaggeration to say the Zimmerman Telegram brought the United States into the conflict. Germany’s policy of unrestricted submarine warfare deserves much of the credit. But the telegram helped convince the American public that their soldiers should be sent to Europe to fight.

The telegram had proved the perfect reason for a policy change and to satisfy doubters.

The value of intercepting messages wasn’t lost on some American and British officials. Early in the Second World War, prior to America formally joining the war, it sent a team of its top code-breakers on a covert mission to Britain to foster a relationship with their counterparts which led to the key intelligence agencies GCHQ and the NSA, BBC News reported.

They also have an agreement which means that for the most part they’re not supposed to spy on each other.