In 1958, the United States developed a secret project to explode an atomic bomb on the surface of the moon. The explosion, when seen from Earth, should have made it clear to the Soviet Union who was the boss when it came to the space race.

In addition, it was believed that such an experiment would bolster the patriotism of the American people.

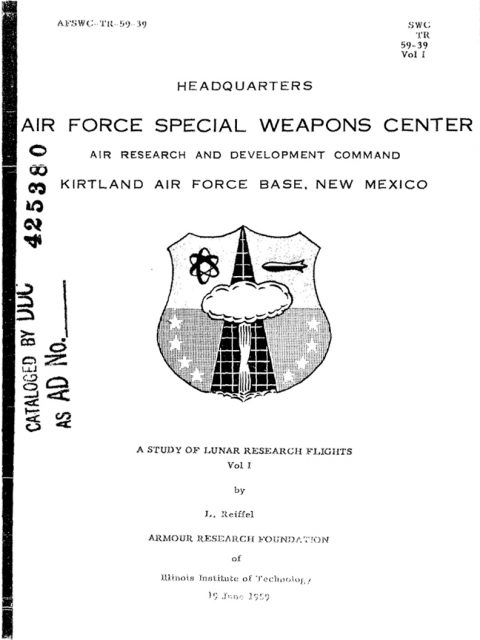

The project was code-named “A119“ and was developed under the auspices of the US Air Force. To preserve confidentiality, the project was called “A Study of Lunar Research Flights.”

In 2000, thanks to the project manager, Leonard Reiffel, the public became aware of some of the details of the planned lunar bombardment.

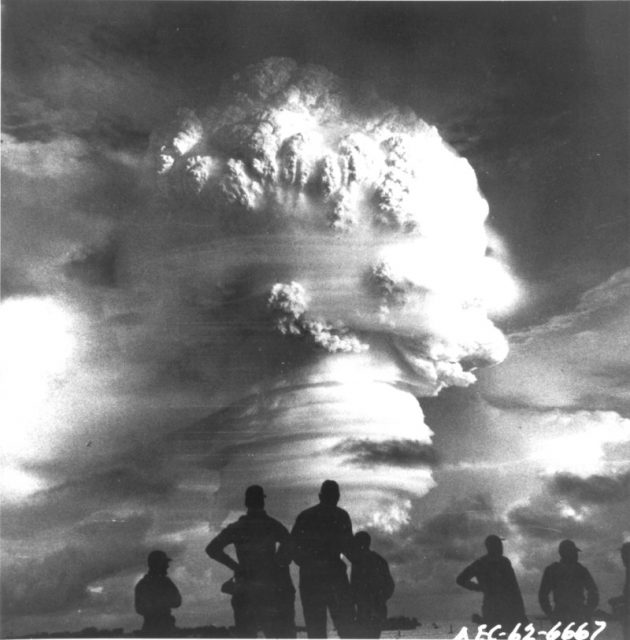

In an interview, Reiffel stated: “It was quite clear that the main purpose of the explosion was to show who the leader was. The air force wanted the mushroom cloud to be so large that it could be seen from Earth.”

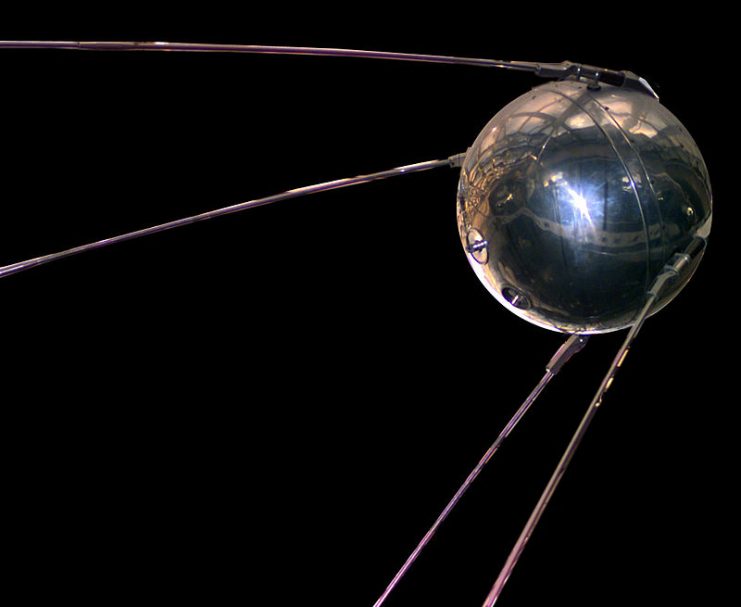

The project came about because on October 4, 1957, the Soviet Union won part of the space race by launching Sputnik 1. This was the first artificial satellite to be sent into Earth’s orbit.

The American government had been following its own program to launch their satellite, Vanguard, in the hopes that it would be the world’s first artificial satellite. They were understandably unhappy that the Russians had beat them to it.

In revenge, the United States introduced a number of new research and projects that ultimately led to the creation and launch of the artificial Earth satellite, Explorer-1.

The successful launch of Sputnik initiated the start of a new space race. This led to the creation of advanced defense research institutes and projects such as NASA and DARPA. But it also led to a study on how the Americans might nuke the moon.

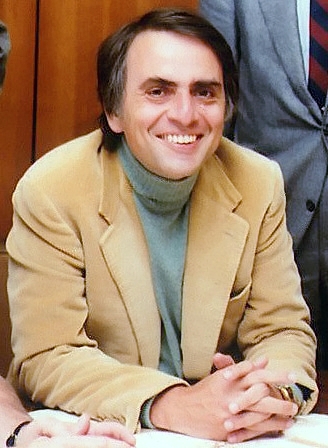

This study involved a team of 10 people headed by Leonard Reiffel. Among the members of the research group was astronomer Gerard Kuiper, and his doctoral student, Carl Sagan, who was engaged in mathematical modeling of the expansion of a dust cloud in space around the moon. Studies were conducted at the Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago.

The project initially planned to use a thermonuclear bomb. However, this caused problems. The weight of such a device was so great that they didn’t have enough launch vehicles capable of putting it into near-earth orbit or of delivering sufficient cargo to the Moon.

As a result, the U.S. Air Force abandoned this idea. Instead, they decided to use a W25 warhead since this was of a relatively small size, weight, and power (1.7 kilotons).

According to the plan, the launch of the W25 was to be carried out with the help of a carrier rocket. The rocket was supposed to explode when hitting the surface on the far side of the Moon.

A cloud of dust, formed as a result of the explosion, would have risen to a great height. Once illuminated by the rays of the sun, this cloud could be seen from the Earth. According to Reiffel, the progress of the Air Force in the development of intercontinental missiles in 1959 would have allowed such a launch.

Despite the global plans and serious preparation in 1959, the Air Force canceled the project without announcing the reasons. There is an assumption that the leaders and initiators of the project were afraid of the public reaction to such a stunt.

There is also a suggestion that in the case of an unsuccessful launch, project A119 represented a danger to the population of the planet.

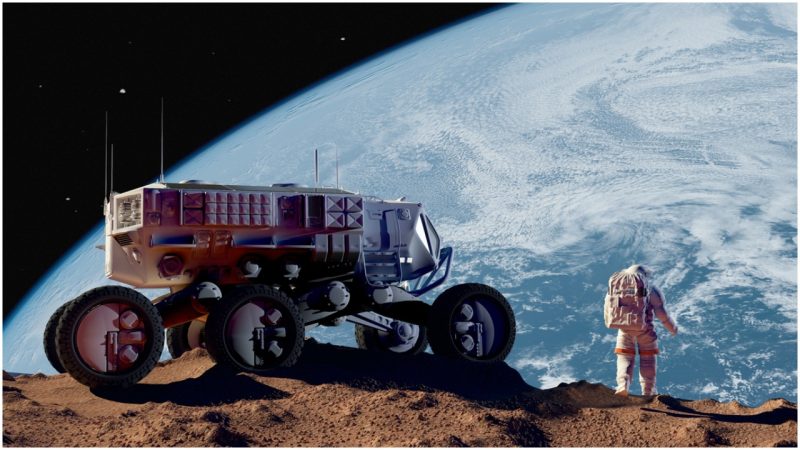

Leonard Reifel also argued that if the operation were successful, large areas of the Moon would be exposed to radioactive contamination. Since there is a possibility that these territories could be used to colonize the moon in the future, introducing any radioactive material was deemed unacceptable.

There were a number of Soviet projects codenamed Project E which had similar parameters to Project A119. Project E-1 was intended to reach the surface of the moon at the same time as projects E-2 and E-3 sent a probe to the reverse side of the moon to take pictures of it.

The final stage of the E-4 project was to be a nuclear strike on the moon. These projects were canceled at the planning stage due to concerns about the reliability and safety of the launch vehicle.

In 1963, the USSR, the USA, and Great Britain signed the treaty Banning Nuclear Weapon Tests in the Atmosphere, in Outer Space, and Under Water. In 1967, another space treaty was signed in which future research into the effects of nuclear explosions on the surface of the moon was prohibited.

However, prior to the signing of the treaty, the USSR and the USA conducted several high-altitude nuclear explosions such as operations Dominic, Argus, K Project, and Hardtack I.

In 1969, after the success of the Apollo 11 mission, the USA became the leader in the space race. The existence of project A119 remained a secret until the mid-1990s.

Writer Kay Davidson, while researching the documents necessary for writing a biography of Karl Sagan, discovered information about a secret project.

His participation in A119 was mentioned on his application for an academic scholarship from the Miller Institute at the University of California at Berkeley in 1959. In a statement, Sagan gave detailed information and revealed the name of the two secret documents on project A119.

Read another story from us: How Nazi Scientists Came To Work In The US After World War II

Forty years later, the book A Study of Lunar Research Flights — Volume I was published.

It revealed that many documents and project reports were destroyed in 1980 at the Illinois Institute of Technology. David Lowry, a nuclear historian from the UK, commented that had the projects gone ahead, “we would probably never have had the romantic image of Neil Armstrong taking ‘one giant leap for mankind’.”