Fighting was often hand-to-hand and even took place underground in tunnels that had been dug in an abandoned chalk quarry.

Last month, the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa put six of the most prestigious military honors in the Western World on display. The Victoria Cross (VC) is the highest military award bestowed by the British government.

Until 1993, Canada, as a member of the British Commonwealth, received these honors from the British government. In 1993, Canada instituted the Canadian Victoria Cross, but it has not been awarded since its creation, and the British version has not been awarded since the end of World War II.

Ninety-three Canadians have been awarded the VC for valor since the medal was created in 1856. Six of them were awarded for one battle in the First World War: the Battle of Hill 70.

The Battle of Hill 70 which took place in August 1917 was a crucial moment for the Canadian contingent sent to the Western Front in WWI. The battle, the first by Canadian troops under exclusively Canadian command, was vital in keeping attacking German forces from the flanks of the British fighting at Passchendaele, the 3rd Ypres battle, just a few miles away.

The Canadians were also tasked with making the German position at the nearby city strong-point of Lens indefensible in the hope that a later breakthrough could be achieved.

Located just under 38 miles south of Ypres, where the British overall commander Douglas Haig had ordered yet another offensive, the German-occupied city of Lens could be observed quite easily from Hill 70, which was named for its height in meters. Haig, who had a reputation for ordering bloody frontal assaults, ordered the Canadians to take Lens in yet another unimaginative attack against the German defenses.

https://youtu.be/tx41dFGvurQ

General Sir Arthur Currie, in command of the Canadian Corps, convinced Haig that rather than waste lives in a frontal attack on Lens, the Canadians should take Hill 70 to the north and install heavy artillery on the summit.

This would make German movement in and around Lens almost impossible and would force the Germans to give up the city. This would result in the line being pushed back, taking some of the pressure off the British to the north and perhaps even opening a hole in German lines that could to be exploited.

On August 15, the Canadians began their assault on Hill 70. The attack took the Germans by surprise, and within a few hours, the Canadians had driven them from the hill.

WWII history buffs know that the Germans were famous for their fierce and almost immediate counter-attacks during that conflict. But this strategy started long before, and the Germans in 1917 launched an amazing 21 counter-attacks on the Canadians on Hill 70 over the next four days.

Fighting was often hand-to-hand and even took place underground in tunnels that had been dug in an abandoned chalk quarry. Some of the soldiers left lasting reminders of having been there, and their carved messages can still be seen today.

Tens of thousands of troops from both sides took part in the battle: the four divisions of the Canadian Corps and a roughly equal number of Germans. Canadian losses amounted to 9,000 killed or wounded. German losses were far greater, approaching 25,000 killed or wounded.

Six Canadians were awarded the Victoria Cross for their actions during the battle. All six of these medals are on display in Ottawa (all are originals, except one, which was lost in 1920 and replaced).

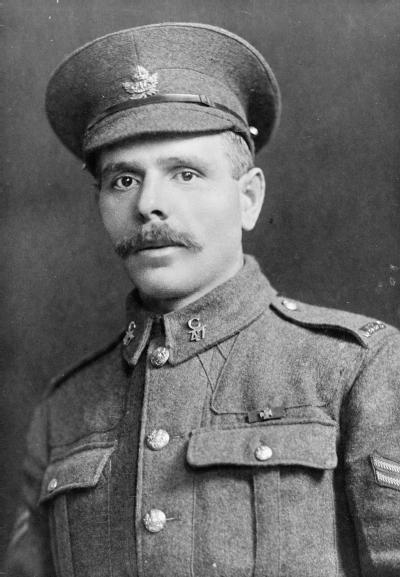

The recipients were: Privates Harry Brown and Michael James O’Rourke, Corporal Filip Konowal, Sergeant Major Robert Hill Hanna, Sergeant Frederick Hobson, and Acting Major Okill Massey Learmonth.

Though all of the recipients’ stories are amazing and note-worthy, one in particular stands out – that of Corporal Konowal.

Konowal had emigrated to Canada from Kutkivski, Russia (now in Ukraine) after having served in the Russian Imperial Army for five years as a hand-to-hand combat instructor. Arriving in Canada in 1913, he worked for a year as a lumberjack and then in a match factory. In 1915, he joined the Canadian Army.

At one point during the war, he was almost shot for desertion. He had been standing guard duty in waist-deep water when he had had enough and charged German lines single-handedly. He captured three machine gun positions and took three prisoners, but initially, his British captain thought he was deserting. Before he came back to explain his actions, orders were issued for Konowal’s arrest.

The citation for his VC reads:

“His section had the difficult task of mopping up cellars, craters and machine-gun emplacements. Under his able direction all resistance was overcome successfully, and heavy casualties inflicted on the enemy. In one cellar he himself bayonetted three enemy and attacked single-handed seven others in a crater, killing them all. On reaching the objective, a machine-gun was holding up the right flank, causing many casualties. Cpl. Konowal rushed forward and entered the emplacement, killed the crew, and brought the gun back to our lines. The next day he again attacked single-handed another machine-gun emplacement, killed three of the crew, and destroyed the gun and emplacement with explosives.”

He attacked until he was shot in the head. He was sent home after a period of recovery in France but had sustained some lasting brain damage. Such a grievous injury came into play later in his life when Konowal was arrested for murder in 1919.

The victim was a man named Bill Artick. Konowal and a veteran friend, Leontiy Diedek, went to see Artick about buying a bicycle, and a dispute arose between Artick and Diedek. According to Konowal, Artick produced a knife, which Konowal seized and shoved into the man’s chest. Others at his trial said the knife belonged to the veteran.

In one of history’s earliest instances, experts testified that both battlefield mental trauma (today referred to as PTSD) and Konowal’s brain injury had caused flashbacks and lack of control. The VC recipient was found not guilty by reason of insanity and placed in a mental institution for seven years.

Upon his release, Konowal got a job as a janitor at the Canadian Parliament. In 1936, Konowal’s situation came to the attention of Mackenzie King, the prime minister. King arranged for the veteran to be given a job for life at Parliament, becoming a doorman at one of the institution’s meeting rooms.

In 1942, Konowal was asked to testify before a committee on orders and decorations. His appearance as a run-down old man in a poor-fitting, shabby suit shocked many of the members, one of whom said: “I think a man awarded the Victoria Cross is entitled to live better than this man, whether he is employed or not.”

Former Corporal Konowal was granted a small pension but continued in his job until his death in 1959. The VC on display in Ottawa today got there the hard way, having been stolen from the museum in 1973 and reacquired after an investigation of the black market in war memorabilia in 2004.